Dance and Music

The Fool: Restlessness and Forgetting God

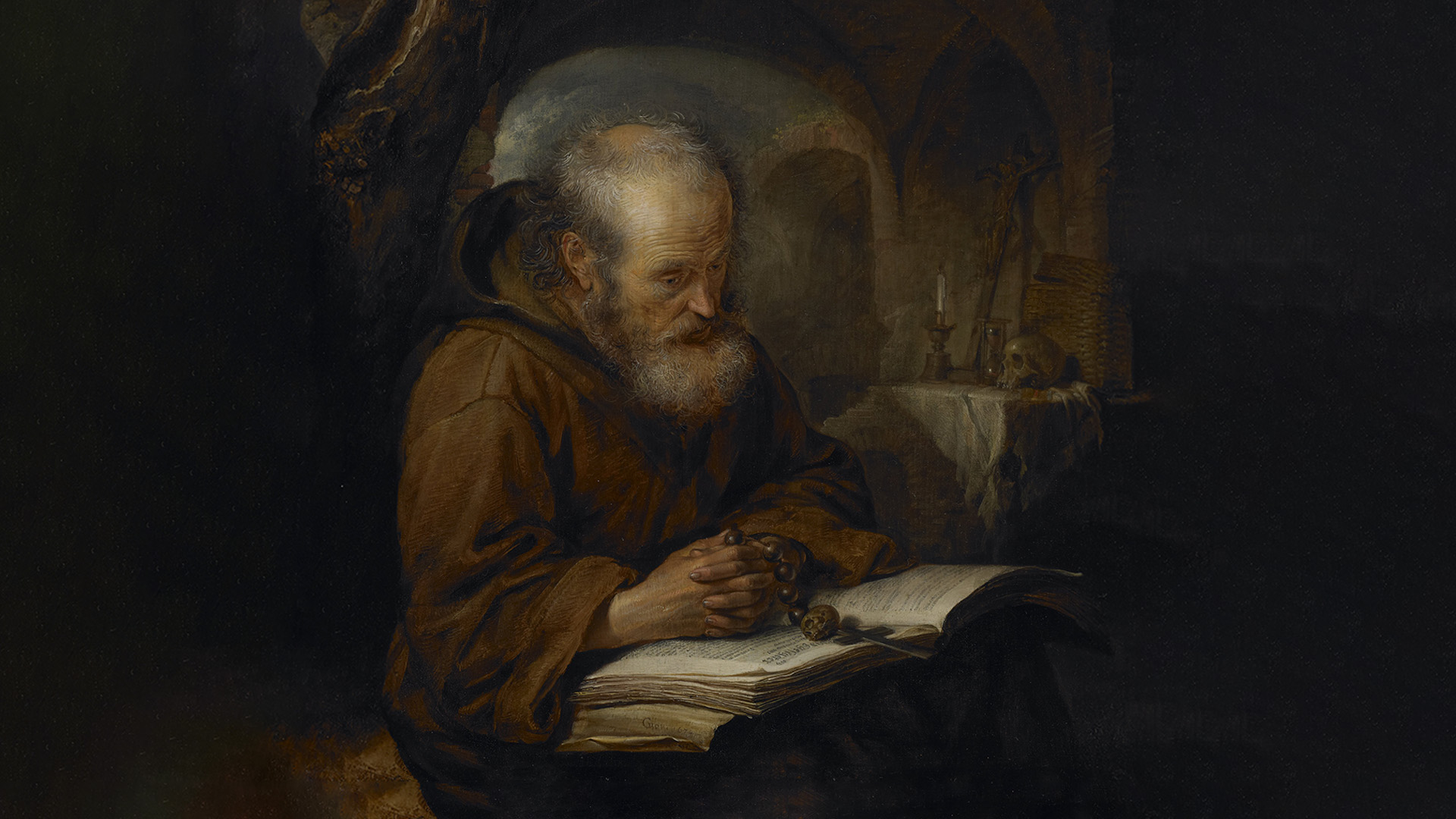

Fools ignore the ideal of a devout existence: They do not pray, they are always on the move, and they cause unrest. In paintings of the 15th and 16th centuries – the first flourishing of the idea of the fool in art and literature – fools therefore always appear as restless, bustling figures. Often, artists even deliberately contrasted them with exemplary, pious and God-fearing people who are able to find rest. This contrast between wisdom and folly was also represented in the Middle Ages by the pair of figures of the ruler and the jester.

Fool dancing in front of King David praying, miniature from a Psalter for Charles VIII, late 15th century, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Dance Mania under the Donkey-Eared Cap

It is not uncommon for illustrated manuscripts from the late Middle Ages to show entire groups of fools performing wild dances with eccentric contortions. A form of the show dance that was particularly popular at this time was the “Moriskentanz” (“morrice dance”), in which fools with donkey-eared caps, sceptres and bell straps played a central role.

Fools during the “Moriskentanz” in front of critical spectators, manuscript 16th century, The Hague, Rijksmuseum Meermanno-Westreenianum, 10 A 11 fol. 48 v.

Dancing as Foolish Mass Hysteria

Sometimes the fool’s dance could develop into a nightmarish mass phenomenon in the imagination of the artists, where more and more new participants would let themselves be carried away. This type of foolish dance orgy is shown, for example, in a copper engraving by Pieter Heyden from Pieter Bruegel. Here, the fools’ dancing frenzy appears unstoppable.

“Narrentanz”, copper engraving by Pieter Heyden from Pieter Bruegel, 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1895-A18684

The Globe in the Fool’s Hand

By leading each other around by the nose, or making long noses at each other, the fools ultimately represent the pessimistic image of a world that has become foolish and threatens to sink into general folly. The balls that many carry with them (some of which are already rolling around on the floor) are also supposed to be symbols of what happens when the world is in the hands of fools.

“Narrentanz”, copper engraving by Pieter Heyden from Pieter Bruegel, 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-P-1895-A18684, details

Male Dances during Fastnacht

As with the fools themselves, the dance was also part of the festivities. Complicated chain and round dances shaped the image of the city Fastnacht from an early stage. In Nuremberg, butchers in particular had the privilege of a special dance. From 1449 onwards they performed the “Zämertanz” – a dance in which the participants demonstratively led each other on sausage rings. Butchers played a prominent role during Fastnacht for a simple, economic reason. Given they could no longer sell meat from Ash Wednesday for the entire Lent period, they were without income for six weeks. And so, to be able to give their businesses a boost, they were allowed to draw attention to themselves again during Fastnacht by performing spectacular displays. This was the case in other cities and towns, too.

Butchers’ Fastnacht Dance in Nuremberg since 1449, coloured Schembart book drawing from16th century, Berlin Staatsbibliothek, Ms. germ. 492, fol. 22 v. / 23 r.

Comedians and Musicians from Italy

The dancing of the Fastnacht figures – regardless of whether they appeared in the standard fool’s costume with a donkey-eared cap, or in professional clothing like the Nuremberg butchers – has always been a core part of the Fastnacht custom. Wherever foolish or fool-like figures are in action, they dance. This not only applies to the Fastnacht customs of the German-speaking area. It can also be observed throughout Europe. The figures of the Italian Commedia dell’ arte are a prime example. In addition to their role on theatre stages, they also became the most important Fastnacht figures south of the Alps from the 17th century at the latest, and are hard to imagine without dancing: There is no contemporary image in which they do not play music and present themselves in more or less comical dance poses.

Dancing figures of the Commedia dell’ Arte, coloured copperplate engraving by Johann Balthasar Probst from Johann Jakob Schübler, 1729, private collection

Foolish Dance Leader during the Parisian Mask Procession

Like with the Commedia dell’arte, Fastnacht figures of other countries follow the same pattern: they dance passionately. A parade of masks from the 18th century from pre-revolutionary Paris shows the enthusiasm for dance there. The outlandish promenade of the lush Fastnacht festivities (“Jours grasses”) is led by a fool in a bell costume and bearing a sceptre, who lightly dances out in front of the strange procession.

Carnival procession in Paris after the Revolution, coloured engraving, Paris 1804, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Département des Estampes

Fastnacht in a Marching Rhythm

The tradition of Fastnacht fools dancing has not changed to this day. On the contrary: Dance moves involving precise step sequences are mandatory for the participants in traditional Fastnacht processions. In every place in the Swabian-Alemannic region, the fools move in a special way that has often been determined for generations. It is their tireless hopping – done in a way typical of the area and called “jucken” in the local dialect – that creates the atmosphere and, not least, sounds the heavy bells (which many fools wear on leather straps on their upper bodies). And it is only in combination with marches composed especially for Fastnacht – like for the “fools’ jump” in Rottweil, for example – that a grandiose visual and acoustic experience is created for spectators and participants alike (an experience that will not be forgotten in a hurry).

“Fools’ jump” in Rottweil 1912, Rottweil Stadtarchiv Rottweil

Polonaise in Schömberg

In some southwestern German fool strongholds, Fastnacht choreographies even see the costumed participants perform a big dance together, which can last up to an hour. The most prominent example of this can be seen in Schömberg near Balingen, where the polonaise dance (known locally as “Bolanes”) is performed by several hundred masked participants and forms one of the central Fastnacht events.

“Polonaise” in Schömberg, led by big and small “Husar”, photo: Werner Mezger

“Polonaise” in Schömberg Fastnacht, video: Werner Mezger

Made with Military Music

Dance needs music. In fact, music has been part of Fastnacht since the very beginning. In the Middle Ages simple instruments were used to play for the fools, including primitive noisemakers, pots, bagpipes, flutes and drums. Over time, though, Fastnacht melodies became more and more sophisticated. At the end of the 19th century, when the wild “fool’s runs” were formed into orderly processions, specific pieces of music developed along with the fool’s marches which suited the joint marching. Almost every Fastnacht location now has its own fool’s march. The fool’s marches mostly only became popular because they were arranged with military music, or directly used military marches such as the “Altjägermarsch”.

Fastnacht music impressions, photo: Andreas Dangel

Catchy Fastnacht Tunes

There are some real classics amongst the fool’s marches. Some town and city bands have long since become permanent fixtures in their Fastnacht uniforms. The “Stadtmusik Elzach” group, for example, is a particular sight with their pointed hats known as “Tschakos”, and the Fastnacht march they play is one of the most distinctive and catchy in all of southwestern Germany.

“Stadtmusik” in Elzach during Fastnacht, photo: Ralf Siegele

The Swiss Answer to German Marches

The fashion of accompanying Fastnacht festivities with marching music that quickly spread in Wilhelmine Germany was met with little approval in Switzerland. As a result, the “Guggemusiken” emerged in and around Basel, supposedly as a parody of overly militaristic German music. A notably Swiss music characteristic of Fastnacht festivities, it involves deliberately quirky (and very loud) sounds being produced from worn, dented brass – instead of the sound of perfectly pitched melodies from sparkling bright instruments. This was the Swiss answer to the Germans and their military music.

“Guggemusik” in Basel, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de