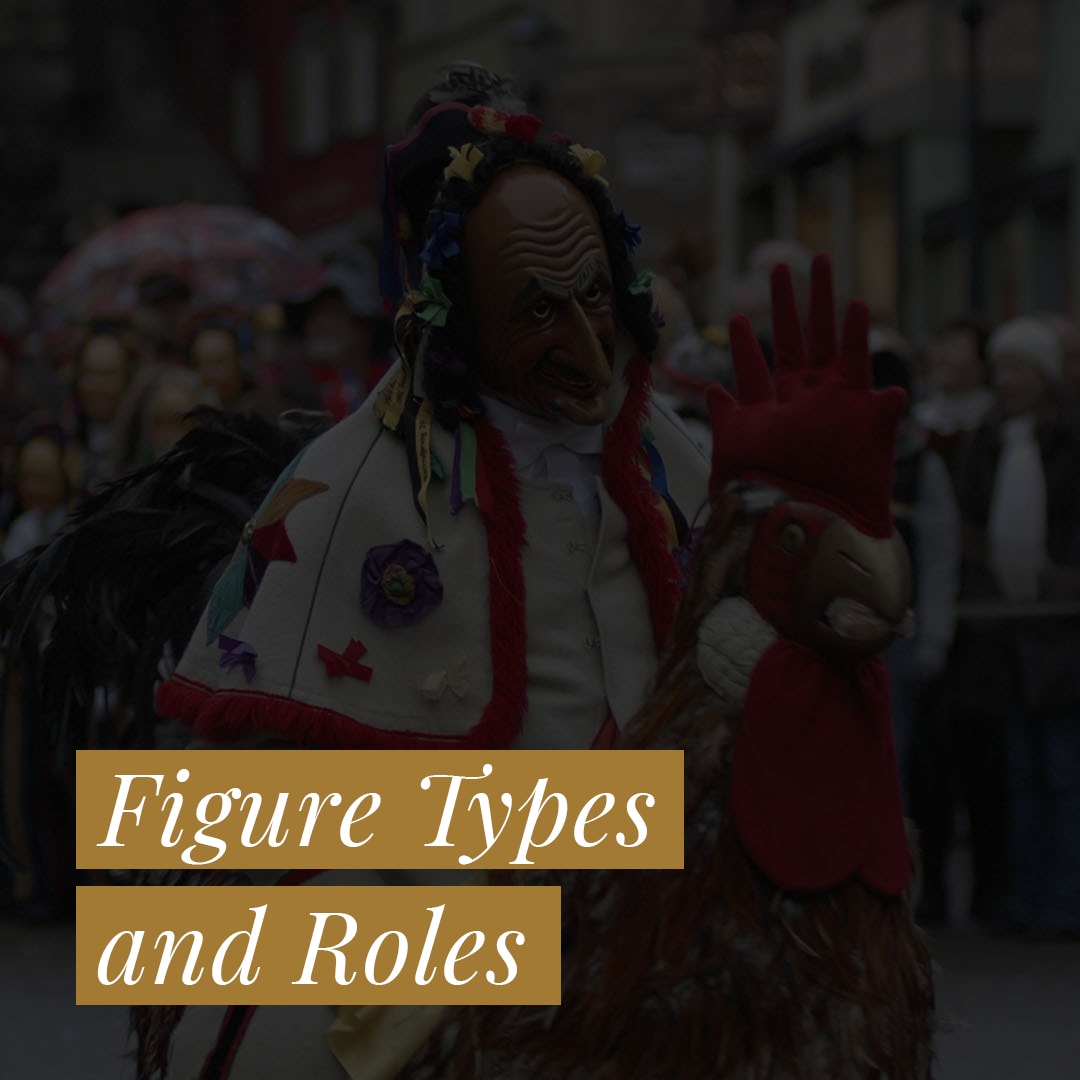

Figure Types and Roles

Ancestor of all Fools: The Devil

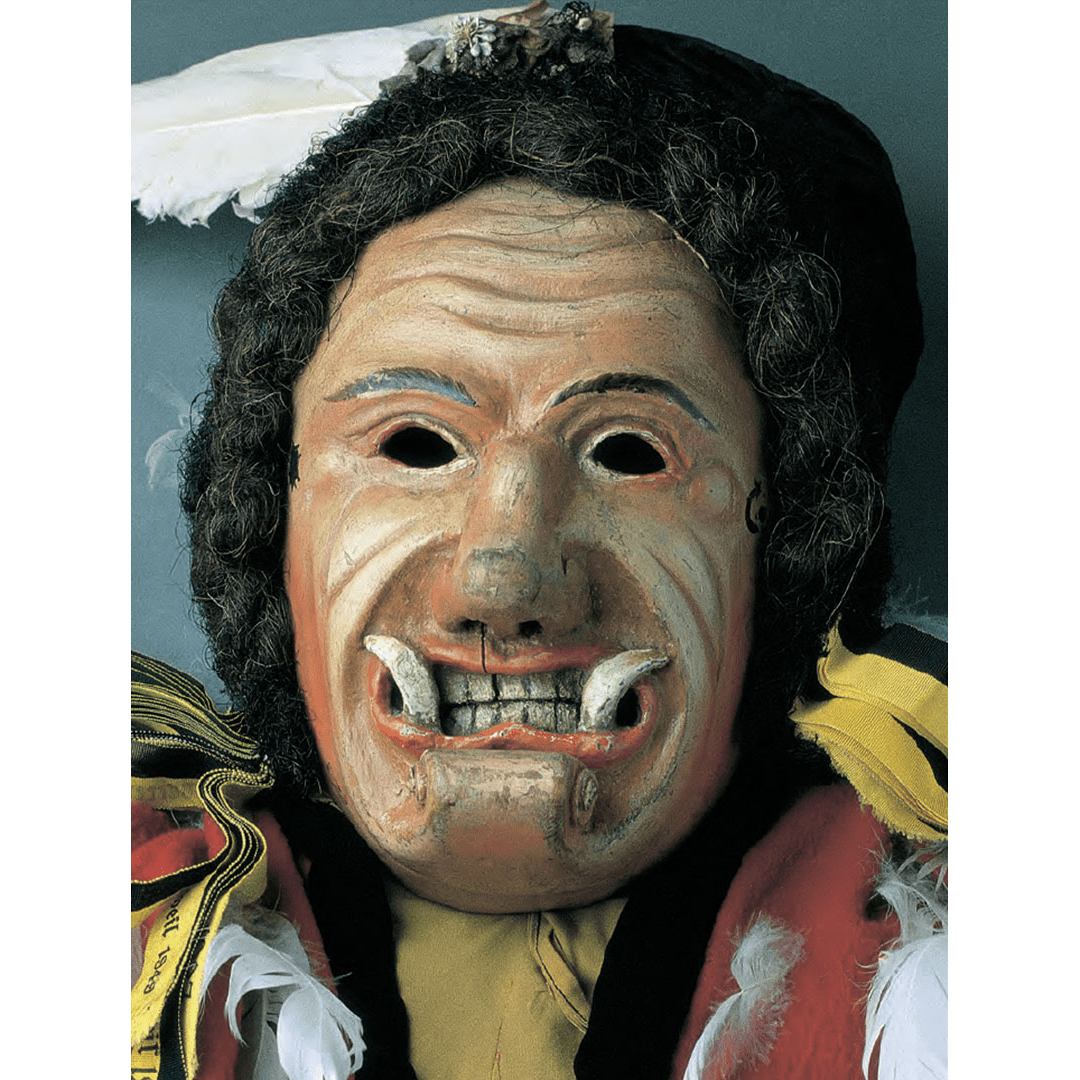

The earliest masked figures during Fastnacht were devils and demons. The reason for the central position of this type of figure was the contrast that 15th century theology in particular liked to construct between Fastnacht and Lent: In line with the view of St. Augustine, who made a distinction between the “State of God” and the “State of the Devil” in his main work “De citivate Dei”, the preachers of the late Middle Ages interpreted Lent positively as a period of holy reflection, while Fastnacht was a period of rule by the devil. Consequently, at first it was exclusively demonic creatures that dominated Fastnacht festivities. Sadly, only fragments of the original devil masks from the 15th century have survived. The Rottweiler “Federhannes” shown here – a classic devil figure of the southwestern German Fastnacht – goes back to the 18th century.

“Federehannes” face mask (“‘s Marxbecke-Federehannes”), 18th century, private collection, photo: Werner Mezger

From Liturgical Theatre to Fastnacht

Devils and demons, the oldest masked figures of Fastnacht, still represent an important group among the Swabian-Alemannic masked figures to this day. Striking members of this family are also the “Schuttige” from Elzach, with their grim face masks and straw-braided tricorns decorated with snail shells. The red and occasionally black woolen balls on the headdress are almost reminiscent of the “Bollenhut” of the Gutach traditional costume, although the “Schuttige” have no connection with it. The fact that devil masks were not originally made for Fastnacht, but rather were primarily used to depict scenes of hell in late medieval figural processions, is largely forgotten today. But, it was actually the procession system from which the devils were then adopted into Fastnacht.

Two “Schuttige”, devil figures from Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

From Liturgical Theatre to Fastnacht

Devils and demons, the oldest masked figures of Fastnacht, still represent an important group among the Swabian-Alemannic masked figures to this day. Striking members of this family are also the “Schuttige” from Elzach, with their grim face masks and straw-braided tricorns decorated with snail shells. The red and occasionally black woolen balls on the headdress are almost reminiscent of the “Bollenhut” of the Gutach traditional costume, although the “Schuttige” have no connection with it. The fact that devil masks were not originally made for Fastnacht, but rather were primarily used to depict scenes of hell in late medieval figural processions, is largely forgotten today. But, it was actually the procession system from which the devils were then adopted into Fastnacht.

Two “Schuttige”, devil figures from Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Young Variant: Witch Figures

A relatively young variant of the demonic figures during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities are the witches. They exist in southwestern Germany only since the early 1930s, while they have a longer tradition in Fastnacht festivities in Tyrol. With their headscarves, (mostly checked) smocks and skirts, straw shoes and broom in hand, they hark back to the fairy tale illustrations of the 19th century and have nothing to do with the tragic women accused of witchcraft – whose persecution and destruction belongs to the dark chapters of history before the Enlightenment. Fastnacht witches are very active and comical, and so are very popular as a type of role that remains “flexible”, especially in guilds that are only a few decades old. The witches from Gengenbach shown here, however, were among the first to appear in the Swabian-Alemannic region.

“Hexen” from Gengenbach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Young Variant: Witch Figures

A relatively young variant of the demonic figures during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities are the witches. They exist in southwestern Germany only since the early 1930s, while they have a longer tradition in Fastnacht festivities in Tyrol. With their headscarves, (mostly checked) smocks and skirts, straw shoes and broom in hand, they hark back to the fairy tale illustrations of the 19th century and have nothing to do with the tragic women accused of witchcraft – whose persecution and destruction belongs to the dark chapters of history before the Enlightenment. Fastnacht witches are very active and comical, and so are very popular as a type of role that remains “flexible”, especially in guilds that are only a few decades old. The witches from Gengenbach shown here, however, were among the first to appear in the Swabian-Alemannic region.

“Hexen” from Gengenbach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Seductive Beauty: White Fools

The “white fools”, which include the “Stadthansel” from Bräunlingen shown here, are a kind of culmination to the traditional Fastnacht in southwestern Germany. The main area of these characteristic figures is on the Baar – the landscape surrounding the origin of the Danube. Their wrinkle-free, smiling rosa-cheeked masks – which have a feminine appearance and are referred to as “polished face masks” – can be traced back to 1500 in northern Italy, from where their importation to southern Germany can be easily followed. They may seem, at first glance, a long way off from the devils and demons. But on closer inspection there is something seductive about them. And it was precisely in this context of the history of ideas that they originally appeared, as we now know from visual evidence from the early modern period. Typical of the “white fools” (and hence their name) are their painted white linen robes and the bells that they wear on crossed leather straps on their chest and back.

“Bräunlinger Stadthansel”, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Seductive Beauty: White Fools

The “white fools”, which include the “Stadthansel” from Bräunlingen shown here, are a kind of culmination to the traditional Fastnacht in southwestern Germany. The main area of these characteristic figures is on the Baar – the landscape surrounding the origin of the Danube. Their wrinkle-free, smiling rosa-cheeked masks – which have a feminine appearance and are referred to as “polished face masks” – can be traced back to 1500 in northern Italy, from where their importation to southern Germany can be easily followed. They may seem, at first glance, a long way off from the devils and demons. But on closer inspection there is something seductive about them. And it was precisely in this context of the history of ideas that they originally appeared, as we now know from visual evidence from the early modern period. Typical of the “white fools” (and hence their name) are their painted white linen robes and the bells that they wear on crossed leather straps on their chest and back.

“Bräunlinger Stadthansel”, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

The Reverse of Beautiful: The ‘Wuescht’

A notion that is often encountered during Fastnacht is the representation of opposites: big – small, young – old, beautiful – ugly, and more. Following this pattern, the graceful “white fools” also have a negative counterpart. In Villingen, it is the “Wuescht” (“the ugly one”). Here, the supreme elegance of the “white fool” in Villingen is reversed: The baroque harem trousers are stuffed with straw until they bulge and obstruct the walk of the wearer. The painted linen garments are tattered, and the often visibly damaged face masks (called a “Scheme” in Villingen) are held to the side away from the face, so that even the basic rule of anonymity no longer applies. In this way, the “Wuescht” group represent the other side of the elegant “white fool”.

“Wuescht” from Villingen, photo: Ralf Siegele , www.ralfsiegele.de

The Reverse of Beautiful: The ‘Wuescht’

A notion that is often encountered during Fastnacht is the representation of opposites: big – small, young – old, beautiful – ugly, and more. Following this pattern, the graceful “white fools” also have a negative counterpart. In Villingen, it is the “Wuescht” (“the ugly one”). Here, the supreme elegance of the “white fool” in Villingen is reversed: The baroque harem trousers are stuffed with straw until they bulge and obstruct the walk of the wearer. The painted linen garments are tattered, and the often visibly damaged face masks (called a “Scheme” in Villingen) are held to the side away from the face, so that even the basic rule of anonymity no longer applies. In this way, the “Wuescht” group represent the other side of the elegant “white fool”.

“Wuescht” from Villingen, photo: Ralf Siegele , www.ralfsiegele.de

From Patchwork Dress to Elegant Garment

A very large group of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht figures is characterised by wearing garments made of scale-like pieces of fabric sewn on top of each other (called “Blätzle”, “Fleckle” or “Spättle”, depending on the region). This patchwork was originally a cheaply sewn-together dress made of textile scraps, but today the fabric scales are made especially for the fools themselves and then sewn piece by piece onto a basic garment in a long labour process. Traditional examples of these dresses made from “Blätzle” are the “Narronen” (the plural of “Narro”) from Laufenburg am Hochrhein. Their current appearance is the result of an ongoing refinement process: In addition to layout of the Blätzle, careful attention is paid to the colour scheme, and every Narro from the German-Swiss twin town bears the city coat of arms on the back. The original dress garment has now become a “dress of honour” (as participants call it), as it is considered a high honour in Laufenburg to be able to wear the special dress.

“Narronen” from Laufenburg, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

From Patchwork Dress to Elegant Garment

A very large group of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht figures is characterised by wearing garments made of scale-like pieces of fabric sewn on top of each other (called “Blätzle”, “Fleckle” or “Spättle”, depending on the region). This patchwork was originally a cheaply sewn-together dress made of textile scraps, but today the fabric scales are made especially for the fools themselves and then sewn piece by piece onto a basic garment in a long labour process. Traditional examples of these dresses made from “Blätzle” are the “Narronen” (the plural of “Narro”) from Laufenburg am Hochrhein. Their current appearance is the result of an ongoing refinement process: In addition to layout of the Blätzle, careful attention is paid to the colour scheme, and every Narro from the German-Swiss twin town bears the city coat of arms on the back. The original dress garment has now become a “dress of honour” (as participants call it), as it is considered a high honour in Laufenburg to be able to wear the special dress.

“Narronen” from Laufenburg, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Fabric Face Mask

As a fairly young guild compared to Laufenburg, the “Blätzlebuebe” from Konstanz (founded in 1933) even bear the characteristic of their garment in their name. As is common in the Bodensee area, even the disguise of their faces does not take place using a wooden face mask: Like the garment, the masks are also composed of “Blätzle” in a certain layout. The hint of a cockscomb runs over the top in red. In contrast to Laufenburg – where the fabric patches are relatively small and angular – somewhat larger, rounded “Blätzle” are used in Konstanz.

“Blätzebuebe” from Konstanz, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Fabric Face Mask

As a fairly young guild compared to Laufenburg, the “Blätzlebuebe” from Konstanz (founded in 1933) even bear the characteristic of their garment in their name. As is common in the Bodensee area, even the disguise of their faces does not take place using a wooden face mask: Like the garment, the masks are also composed of “Blätzle” in a certain layout. The hint of a cockscomb runs over the top in red. In contrast to Laufenburg – where the fabric patches are relatively small and angular – somewhat larger, rounded “Blätzle” are used in Konstanz.

“Blätzebuebe” from Konstanz, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Tattered Dress and Wire Gauze Face Mask

The “Fossli” from Siebnen in Switzerland wears a costume that is still very close to the original simple garment made of scraps of textile. Its name is the Alemannic diminutive of the Standard German word “Fetzen” (shred, tatter). The small scraps of textile, although also solidly sewn together, appear deliberately ragged and are intended to distinguish the “Fossli” – who hides his face behind a wire gauze face mask – as a poor-looking figure from the other, more elaborate fools in the area.

“Fossli” from Siebnen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Tattered Dress and Wire Gauze Face Mask

The “Fossli” from Siebnen in Switzerland wears a costume that is still very close to the original simple garment made of scraps of textile. Its name is the Alemannic diminutive of the Standard German word “Fetzen” (shred, tatter). The small scraps of textile, although also solidly sewn together, appear deliberately ragged and are intended to distinguish the “Fossli” – who hides his face behind a wire gauze face mask – as a poor-looking figure from the other, more elaborate fools in the area.

“Fossli” from Siebnen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Wool Fringes and Silver Bells

The “Rölli” also comes from Siebnen and represents another special type among the “Fleckle”, “Blätze” and “Spättle” garments: the “Fransennarren” (“fringed fools”). In a clear break from his local counterpart, the “Fossli”, the “Rölli” wears a garment made up of hundreds of small wool thread pompoms arranged in a complicated diamond pattern. His face mask is made of wood and, presumably as a relic of the Biedermeier period, even has a hint of a pair of glasses. The name “Rölli” is derived from the small, silver “roller” bells (small balls with sound slits and a rolling object in the middle, creating a sound) that he wears around his stomach as a “Gschell”. There are also “Fransenkleider” (“fringe dresses”) of a similar kind in Rottweil and Schömberg. The Siebner variant is so dense and so warm for the wearer that the “Rölli” is also called “Bärli” (“bear”) because of its almost fur-like disguise.

“Rölli” from Siebnen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Wool Fringes and Silver Bells

The “Rölli” also comes from Siebnen and represents another special type among the “Fleckle”, “Blätze” and “Spättle” garments: the “Fransennarren” (“fringed fools”). In a clear break from his local counterpart, the “Fossli”, the “Rölli” wears a garment made up of hundreds of small wool thread pompoms arranged in a complicated diamond pattern. His face mask is made of wood and, presumably as a relic of the Biedermeier period, even has a hint of a pair of glasses. The name “Rölli” is derived from the small, silver “roller” bells (small balls with sound slits and a rolling object in the middle, creating a sound) that he wears around his stomach as a “Gschell”. There are also “Fransenkleider” (“fringe dresses”) of a similar kind in Rottweil and Schömberg. The Siebner variant is so dense and so warm for the wearer that the “Rölli” is also called “Bärli” (“bear”) because of its almost fur-like disguise.

“Rölli” from Siebnen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Long-Eared Rarity: The ‘Butzesel’

Animal figures represent an important section of the complete collection of Fastnacht masked figures. According to archival material, they appeared as early as the 15th and 16th centuries during Fastnacht festivities and, at that time, were often associated with the medieval allegories of vice, which linked various sins with certain symbolic animals – for example, unchastity with a goat, sloth with a donkey and gluttony with a pig. This is certainly the origin of the “Butzesel” – an important donkey figure in the Villingen Fastnacht – who drags a fir branch behind him, has sausage rings hanging around his ears and is kept on the go, or is tamed, by several drivers in blue carter’s overalls. Throughout the late Middle Ages, the donkey was considered the symbolic animal of foolishness par excellence – something expressed, not least, in the donkey ears on the fools’ caps. In Villingen, the donkey has become an established figure that has taken on a life of its own.

“Butzesel” from Villingen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Horned Humour: The City Ram

The city ram in Bräunlingen has a similar connection to the donkey in Villingen. The dummy ram is carried by its supposed rider, who is dressed in a “Hanselhäs” (a sort of garment) but does not wear a face mask. Two young boys in a “Hanselhäs” and carter’s overalls (also unmasked) try to keep the ram in check with ropes, while two adult drivers dressed in the same clothes (but with face masks) prompt it to all kinds of unexpected actions by cracking whips. The medieval moral significance of the ram as an animal allegory of unchastity is no longer apparent to anyone here. Today, the group of five is particularly valued for its humour, which lies in the stubborn nature of the animal figure and its rider – in their “obstinacy”.

“Stadtbock” from Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Horned Humour: The City Ram

The city ram in Bräunlingen has a similar connection to the donkey in Villingen. The dummy ram is carried by its supposed rider, who is dressed in a “Hanselhäs” (a sort of garment) but does not wear a face mask. Two young boys in a “Hanselhäs” and carter’s overalls (also unmasked) try to keep the ram in check with ropes, while two adult drivers dressed in the same clothes (but with face masks) prompt it to all kinds of unexpected actions by cracking whips. The medieval moral significance of the ram as an animal allegory of unchastity is no longer apparent to anyone here. Today, the group of five is particularly valued for its humour, which lies in the stubborn nature of the animal figure and its rider – in their “obstinacy”.

“Stadtbock” from Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Feathered Womaniser: The ‘Guller’ (Rooster)

“Schiermaiers Guller”, an oversized rooster that is also “carried” by a rider and which is seen during the Rottweiler Fasnet, is more self-explanatory in terms of its symbolism. The rooster as a symbol for sexual desire is still common today. How the Rottweiler “Guller” used to act as part of its role during the festivities points quite clearly in this direction: According to oral tradition, it is said to have had a pole with it which it let young girls ride on. There are similar individual figures in other southwestern German Fastnacht festivities, among which the “Gullerreiter” (“Rooster Rider”) from Wolfach in the Kinzigtal is probably the best known. The name “Schiermaiers Guller” in Rottweil refers to the head of the municipal granary, the “Maior domus”, who kept chickens and also owned a rooster.

“Schiermaiers Guller” from Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Feathered Womaniser: The ‘Guller’ (Rooster)

“Schiermaiers Guller”, an oversized rooster that is also “carried” by a rider and which is seen during the Rottweiler Fasnet, is more self-explanatory in terms of its symbolism. The rooster as a symbol for sexual desire is still common today. How the Rottweiler “Guller” used to act as part of its role during the festivities points quite clearly in this direction: According to oral tradition, it is said to have had a pole with it which it let young girls ride on. There are similar individual figures in other southwestern German Fastnacht festivities, among which the “Gullerreiter” (“Rooster Rider”) from Wolfach in the Kinzigtal is probably the best known. The name “Schiermaiers Guller” in Rottweil refers to the head of the municipal granary, the “Maior domus”, who kept chickens and also owned a rooster.

“Schiermaiers Guller” from Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Always on the Go: The ‘Brieler Rössle’

Probably the most spectacular animal figures seen during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities are the “Brieler Rössle” from Rottweil. Named after a former small village or hamlet near Rottweil called Briel, the “Rössle” behave with particular showmanship at the beginning and end of the “Narrensprung” (“fools’ jump”): A rider performs all kinds of daring jumps with a mock-up horse, while two drivers try to restrain it with deafening whip lashes that sometimes sound like volleys. The lashes are always aimed at the rider’s face mask cover, with the drivers aiming to knock the goose wing off the headpiece of the “Rösslenarr” (“horse fool”).

“Brieler Rössle” from Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Always on the Go: The ‘Brieler Rössle’

Probably the most spectacular animal figures seen during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities are the “Brieler Rössle” from Rottweil. Named after a former small village or hamlet near Rottweil called Briel, the “Rössle” behave with particular showmanship at the beginning and end of the “Narrensprung” (“fools’ jump”): A rider performs all kinds of daring jumps with a mock-up horse, while two drivers try to restrain it with deafening whip lashes that sometimes sound like volleys. The lashes are always aimed at the rider’s face mask cover, with the drivers aiming to knock the goose wing off the headpiece of the “Rösslenarr” (“horse fool”).

“Brieler Rössle” from Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Outstanding Appearance: The Tall Man

There is also a tradition during Fastnacht of figures who are dressed up in such a way that they stand out from the rest thanks to their size, build or other mock physical peculiarities. In addition to the “Schwellköpfe” (“bigheads”) that were very popular in the 19th century, these primarily include giants. The “tall man” in Rottweil is an example of this kind of outstanding figure (in the truest sense of the word). Its wearer is hidden under a two-part fabric bell made of blue and red smock cloth that reaches several meters high. The core is a rod with a paper mache head on top. By turning the rod accordingly, the head can look in any desired direction, which gives the impression that the giant can look into the windows of the first floor of the houses along the street. The opposite of the “tall man” is the “fat woman”: While she is only half the size of the man, she features an expansive dress made of tyres and is very corpulent. A duo that appears during a number of southern Italian Fastnacht festivities, and which embodies the contrast between Fastnacht and Lent, could have served as the inspiration for the creation of the tall man and fat woman combination.

“Langer Mann” from Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolish Descendants of the Giant Goliath

The best-known representative of the oversized carnival figures of the Swabian-Alemannic region is undoubtedly the “Gole” from Riedlingen an der Donau who, along with his entourage, is the focus of the town’s Fastnacht festivities. As its Swabian name suggests, it derives from the biblical giant Goliath and so belongs to the circle of figures who represent “deniers of the Christian world view”, as they are typical of the old notion of the fool himself, and his original carnival role of representing remoteness from God. As the main attraction of the Riedlinger Fastnacht, the “Gole” has became so popular among the locals that its number has increased over time, and a whole “Gole” family has now emerged.

“Gole” from Riedlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Simple Rural Disguise: The Straw Bear

The “Strohbären” (“straw bears”) originate from village Fastnacht festivities, but unfortunately they are becoming rarer and rarer. That is because, on the one hand, there is hardly any long straw left in the age of combine harvesting and, on the other, fewer and fewer young boys are prepared to take on the inconvenience of wearing this kind of disguise. In Wilflingen on the southwestern borderline of the Swabian Alb, the ritual is still alive in its original form. There, the protagonist is tied into a type of pyramid made up of bundles of straw with a tuft of ears on the tip and then led around on hemp ropes by drivers (he can only move around with difficulty, and can sometimes hardly find his way around on his own). Straw bears of this kind are, or were, known far beyond the Swabian-Alemannic region as the delight of the Fastnacht season, and even represent a European phenomenon.

“Strohbär” from Wilflingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Simple Rural Disguise: The Straw Bear

The “Strohbären” (“straw bears”) originate from village Fastnacht festivities, but unfortunately they are becoming rarer and rarer. That is because, on the one hand, there is hardly any long straw left in the age of combine harvesting and, on the other, fewer and fewer young boys are prepared to take on the inconvenience of wearing this kind of disguise. In Wilflingen on the southwestern borderline of the Swabian Alb, the ritual is still alive in its original form. There, the protagonist is tied into a type of pyramid made up of bundles of straw with a tuft of ears on the tip and then led around on hemp ropes by drivers (he can only move around with difficulty, and can sometimes hardly find his way around on his own). Straw bears of this kind are, or were, known far beyond the Swabian-Alemannic region as the delight of the Fastnacht season, and even represent a European phenomenon.

“Strohbär” from Wilflingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Straw Bear and Wild Man: The ‘horige Bär’

The “horige Bär” from Singen am Hohentwiel is an optimised – and much more comfortable – form of the straw bear. Instead of binding a participant in straw every year, the rye straw has been replaced by pea straw that is then sewn onto canvas suits, so that the entire costume can be easily put on and taken off. In addition, this refined variant of the straw bear in Singen also features a wooden mask. The improved comfort of wearing the new type of costume has led to a proliferation of the old figure. A group of no less than fourteen “horige Bären” now appear during Fastnacht festivities in Singen. They have departed from the old-style straw bear in their appearance, and now rather resemble the type of “wild man” known from Fastnacht traditions in Tyrol, for example.

“Horiger Bär” from Singen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Straw Bear and Wild Man: The ‘horige Bär’

The “horige Bär” from Singen am Hohentwiel is an optimised – and much more comfortable – form of the straw bear. Instead of binding a participant in straw every year, the rye straw has been replaced by pea straw that is then sewn onto canvas suits, so that the entire costume can be easily put on and taken off. In addition, this refined variant of the straw bear in Singen also features a wooden mask. The improved comfort of wearing the new type of costume has led to a proliferation of the old figure. A group of no less than fourteen “horige Bären” now appear during Fastnacht festivities in Singen. They have departed from the old-style straw bear in their appearance, and now rather resemble the type of “wild man” known from Fastnacht traditions in Tyrol, for example.

“Horiger Bär” from Singen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Import from Italy: The Domino

The Fastnacht figures who came to the Alemannic region through cultural contacts with northern Italy via the Alps form a distinctly separate group. They are particularly present in central Switzerland, where there was constant exchange with the diocese of Milan via the Gotthard. The figure of the domino from Schwyz in central Switzerland is an example of this group. With his Bergamasque face mask and hooded cloak, he originally goes back to a clerical “gentleman” (“Domino” in Italian) whose winter clothing, which had gone out of fashion, was considered humorous and so became a Fastnacht costume. The Bajazzo (“Bajass”) also arrived into the German-speaking area through this method of adopting southern styles. The Italian influences on Fastnacht north of the Alps, which have been increasingly evident since the Baroque, even eventually led to the use of the Latin root name “Carnevale” for the festivities themselves.

“Domino” from Schwyz (CH), photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

On the Street in a Nightgown

Among the figures without face masks of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, by far the largest group are the “Hemdglonker”. Dressed in white nightgowns and wearing sleeping caps, they usually gather on “Schmutziger Dunschtig” (“Dirty Thursday”) for early morning or night-time processions. Some of them also appear on other days. The companions of the “Wohlauf” in Wolfach in the Kinzigtal, for example, do so early on “Schellementig” (Shrove Monday). A very unique variant of the “Hemdglonker” are the “Geltentrommler” from Waldshut am Hochrhein. They parade through the town with flour-whitened faces, drumming with cooking spoons on their wooden tubs hung upside down in front of their stomachs, which are called “Gelten” in the local dialect. They announce the beginning of Fastnacht by chanting to the beat of the drums: “Hüt goht d’Fasnet a mit de rote Pfiife.”

“Geltentrommler” from Waldshut, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

On the Street in a Nightgown

Among the figures without face masks of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, by far the largest group are the “Hemdglonker”. Dressed in white nightgowns and wearing sleeping caps, they usually gather on “Schmutziger Dunschtig” (“Dirty Thursday”) for early morning or night-time processions. Some of them also appear on other days. The companions of the “Wohlauf” in Wolfach in the Kinzigtal, for example, do so early on “Schellementig” (Shrove Monday). A very unique variant of the “Hemdglonker” are the “Geltentrommler” from Waldshut am Hochrhein. They parade through the town with flour-whitened faces, drumming with cooking spoons on their wooden tubs hung upside down in front of their stomachs, which are called “Gelten” in the local dialect. They announce the beginning of Fastnacht by chanting to the beat of the drums: “Hüt goht d’Fasnet a mit de rote Pfiife.”

“Geltentrommler” from Waldshut, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Immortalised Local Originals

Generally appearing as single figures and predominantly without a face mask, these role players are reminiscent of a well-known local original figure, or an eccentric local oddity. One of them is the “Baptistle” from Hüfingen, who carries the frame of a lattice window around his neck. He is reminiscent of a certain Baptist Moog, who is said to have circumvented a Fastnacht ban in a clever way: Once banned from taking part on Fastnacht on the street, the “Baptistle” asked to be allowed to at least watch on from the window. And when he was allowed to do so, he unceremoniously lifted the window frame from its hinges, hung it around his neck and took it out onto the street. This is clearly a wandering legend that is also told in Radolfzell – except that there, the protagonist is known as “Kappedeschle” in reference to Xaver Desch, who always appears wearing a cap. He, too, takes part in the Fasnet procession with a window frame around his neck.

„Babtistle“ aus Hüfingen, Foto: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Immortalised Local Originals

Generally appearing as single figures and predominantly without a face mask, these role players are reminiscent of a well-known local original figure, or an eccentric local oddity. One of them is the “Baptistle” from Hüfingen, who carries the frame of a lattice window around his neck. He is reminiscent of a certain Baptist Moog, who is said to have circumvented a Fastnacht ban in a clever way: Once banned from taking part on Fastnacht on the street, the “Baptistle” asked to be allowed to at least watch on from the window. And when he was allowed to do so, he unceremoniously lifted the window frame from its hinges, hung it around his neck and took it out onto the street. This is clearly a wandering legend that is also told in Radolfzell – except that there, the protagonist is known as “Kappedeschle” in reference to Xaver Desch, who always appears wearing a cap. He, too, takes part in the Fasnet procession with a window frame around his neck.

„Babtistle“ aus Hüfingen, Foto: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolish Law Enforcers

A standard role in many Fastnacht festivities, especially in the Hegau-Bodensee area, is the “fool policeman”, known in the dialect as the “Narrenbolizei”. Like here in Singen, for example, he usually acts as a loud public crier who announces Fasnet with his bell, or as a respect-demanding, foolish law enforcer who makes it clear that it is he who holds executive power during the Fastnacht festivities (and no longer the disempowered officials from the town hall). Fastnacht, therefore, is by no means the dissolution of all order (or even something resembling anarchy) for a brief period of time. This is something even the parodic figure of the “fool policeman” shows. On the contrary: It only creates new orders and follows its own laws, which can almost be as strict as the rules followed during everyday life.

“Narrenbolizei” from Singen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolish Law Enforcers

A standard role in many Fastnacht festivities, especially in the Hegau-Bodensee area, is the “fool policeman”, known in the dialect as the “Narrenbolizei”. Like here in Singen, for example, he usually acts as a loud public crier who announces Fasnet with his bell, or as a respect-demanding, foolish law enforcer who makes it clear that it is he who holds executive power during the Fastnacht festivities (and no longer the disempowered officials from the town hall). Fastnacht, therefore, is by no means the dissolution of all order (or even something resembling anarchy) for a brief period of time. This is something even the parodic figure of the “fool policeman” shows. On the contrary: It only creates new orders and follows its own laws, which can almost be as strict as the rules followed during everyday life.

“Narrenbolizei” from Singen, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Fastnacht Marriage: The Parent Fools

For Fastnacht festivities around the Bodensee area in particular, a pair of figures is mandatory. To a certain extent, they have custody of all fools and can lay claim to all fools being their children for the period between “Dirty Thursday” and Shrove Tuesday Eve: the parent fools. With a few exceptions, both roles – both that of the “father fool” and that of the “mother fool” – are played by male participants. Mostly dressed in traditional local costumes, the two of them go to the front of the procession, as is the case here in Überlingen, and have a prominent position throughout the Fastnacht festivities. Even if no direct line of tradition can be traced back to the late Middle Ages, it is worth mentioning that the figure of the mother fool in particular was already a prominent Fastnacht role in various places in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries and that in Dijon and Augsburg, for example, entire carnival societies gathered around a mother fool, who was also always played by a man.

Fastnacht Marriage: The Parent Fools

For Fastnacht festivities around the Bodensee area in particular, a pair of figures is mandatory. To a certain extent, they have custody of all fools and can lay claim to all fools being their children for the period between “Dirty Thursday” and Shrove Tuesday Eve: the parent fools. With a few exceptions, both roles – both that of the “father fool” and that of the “mother fool” – are played by male participants. Mostly dressed in traditional local costumes, the two of them go to the front of the procession, as is the case here in Überlingen, and have a prominent position throughout the Fastnacht festivities. Even if no direct line of tradition can be traced back to the late Middle Ages, it is worth mentioning that the figure of the mother fool in particular was already a prominent Fastnacht role in various places in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries and that in Dijon and Augsburg, for example, entire carnival societies gathered around a mother fool, who was also always played by a man.

Foolish Offspring: The Fools’ Seeds

During Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, the collective name for children is particularly affectionate. Although they dress up colourfully, children do not yet wear the classic masks and other costume elements. They are called the “fools’ seeds” (“Narrensamen”) and form the offspring that will eventually carry on the Fastnacht tradition in southwestern Germany. In Rottweil, the “fools’ seeds” are dressed in white make-up in a two-coloured or dotted bajazzo costume (as a “Bajässle”) with a frilled collar and a pointed cap, and form an excited crowd before the “fools’ jump” takes place. The figurative term “fools’ seeds” echoes the sowing metaphor for the emergence of new fools that was popular as early as in the late Middle Ages, and which was expressed in the agricultural Fastnacht customs of plough pulling and sowing fools’ seeds.

“Narrensamen” from Rottweil, photo: Wilfried Dold

Foolish Offspring: The Fools’ Seeds

During Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, the collective name for children is particularly affectionate. Although they dress up colourfully, children do not yet wear the classic masks and other costume elements. They are called the “fools’ seeds” (“Narrensamen”) and form the offspring that will eventually carry on the Fastnacht tradition in southwestern Germany. In Rottweil, the “fools’ seeds” are dressed in white make-up in a two-coloured or dotted bajazzo costume (as a “Bajässle”) with a frilled collar and a pointed cap, and form an excited crowd before the “fools’ jump” takes place. The figurative term “fools’ seeds” echoes the sowing metaphor for the emergence of new fools that was popular as early as in the late Middle Ages, and which was expressed in the agricultural Fastnacht customs of plough pulling and sowing fools’ seeds.

“Narrensamen” from Rottweil, photo: Wilfried Dold