Fools as Living Images

‘White fools’ as Walking Works of Art

The most impressive figures amongst the traditional masked figures of the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht are the “white fools”, with their painted linen garments. They are throughout Europe and, through the creative skill and imagination of special painters, literally become walking works of art. They can mostly be found throughout the Baar landscape surrounding the origin of the Danube. But they can also be found on the upper Neckar, in the south of the Swabian Alb and in the Donautal, in northern Hegau and occasionally in Oberschwaben, too. Depending on the local tradition, the motifs on their linen garments (known as “Häs” in Alemannic) are determined by a set motif pattern, or can also be designed more freely. The development of garment painting, which in its present form can be traced back at least to the 18th century, can be reconstructed quite well.

“Narro” from Villingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Fool’s Costume in Donkey Grey

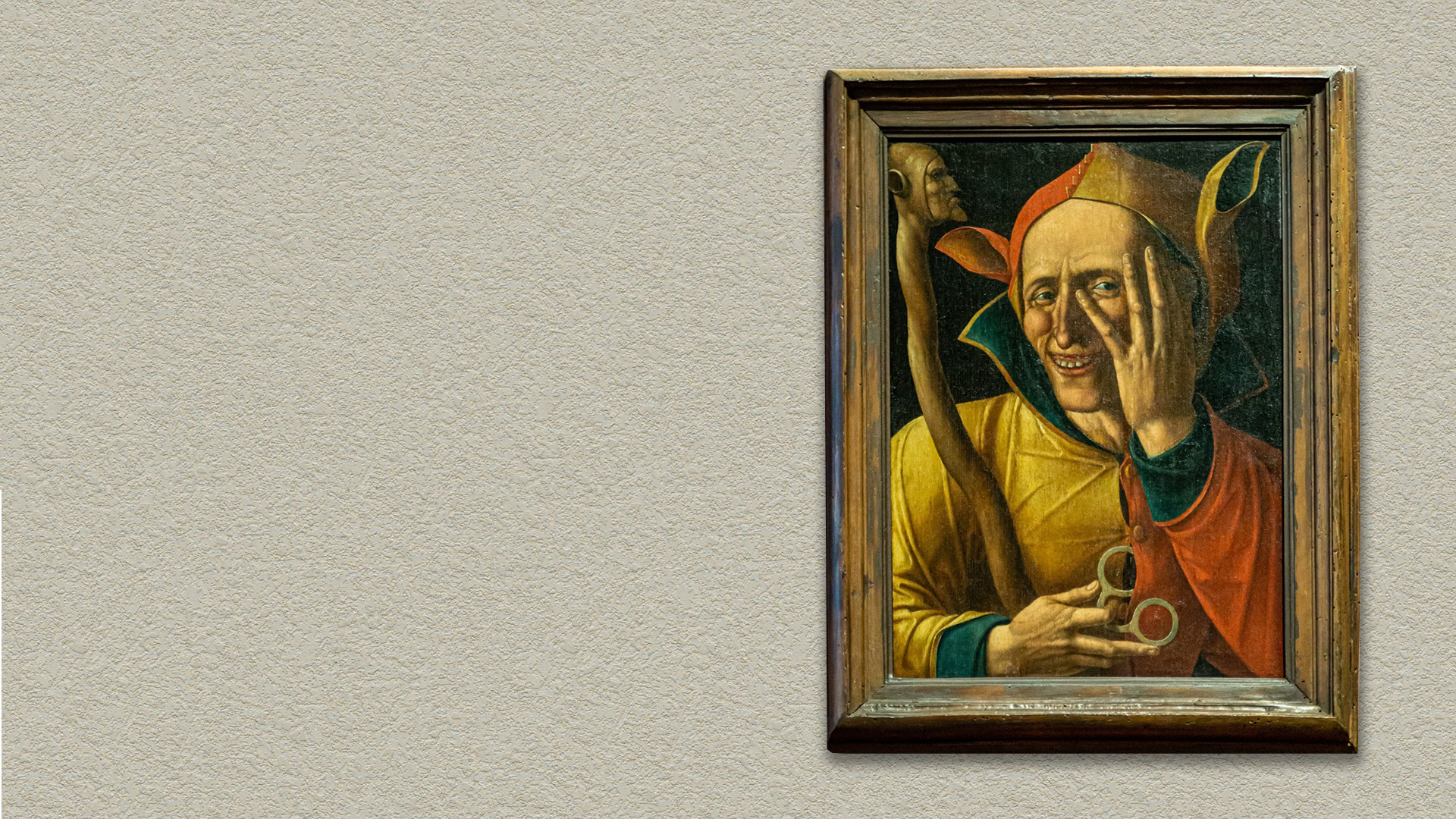

The standard fools of the late Middle Ages had no ornamental or figuratively decorated garments. Even when they acted as court jesters, their clothes were plain. Garment decorations, for example with coats of arms or flowers, were reserved exclusively for the nobility. The fools wore simple hip or knee-length smocks with a round hood which the typical donkey ears were attached to, tight-fitting trousers and generally wore poulaines (shoes with curled tips). The colour of the fool’s costume was mostly grey or brownish, based on the figure of the donkey as an expression of simplicity and stubbornness.

Medieval standard fool in grey, portrait of a fool, painting from the circle of Pieter Aertsen, Netherlands, circa 1550, private property

Fool’s Costume in Donkey Grey

The standard fools of the late Middle Ages had no ornamental or figuratively decorated garments. Even when they acted as court jesters, their clothes were plain. Garment decorations, for example with coats of arms or flowers, were reserved exclusively for the nobility. The fools wore simple hip or knee-length smocks with a round hood which the typical donkey ears were attached to, tight-fitting trousers and generally wore poulaines (shoes with curled tips). The colour of the fool’s costume was mostly grey or brownish, based on the figure of the donkey as an expression of simplicity and stubbornness.

Medieval standard fool in grey, portrait of a fool, painting from the circle of Pieter Aertsen, Netherlands, circa 1550, private property

Two-Tone Split Dress

Not infrequently, the fools’ clothes also followed the medieval fashion of the “mi-parti” and were divided vertically into two coloured halves (preferably red and yellow). The arrangement of the colours on the cap was repeated diagonally and offset on the smock, and mirrored again on the trousers. That meant: cap (red – yellow), smock (yellow – red) and trousers (red – yellow again).

Laughing fool in a red and yellow “mi-parti” looking through the fingers, anonymous painting, Netherlands circa 1530, Stockholm, National Art Museum of Sweden, NBM 6783

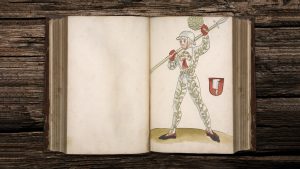

‘Schembartlauf’ Garment Decorations

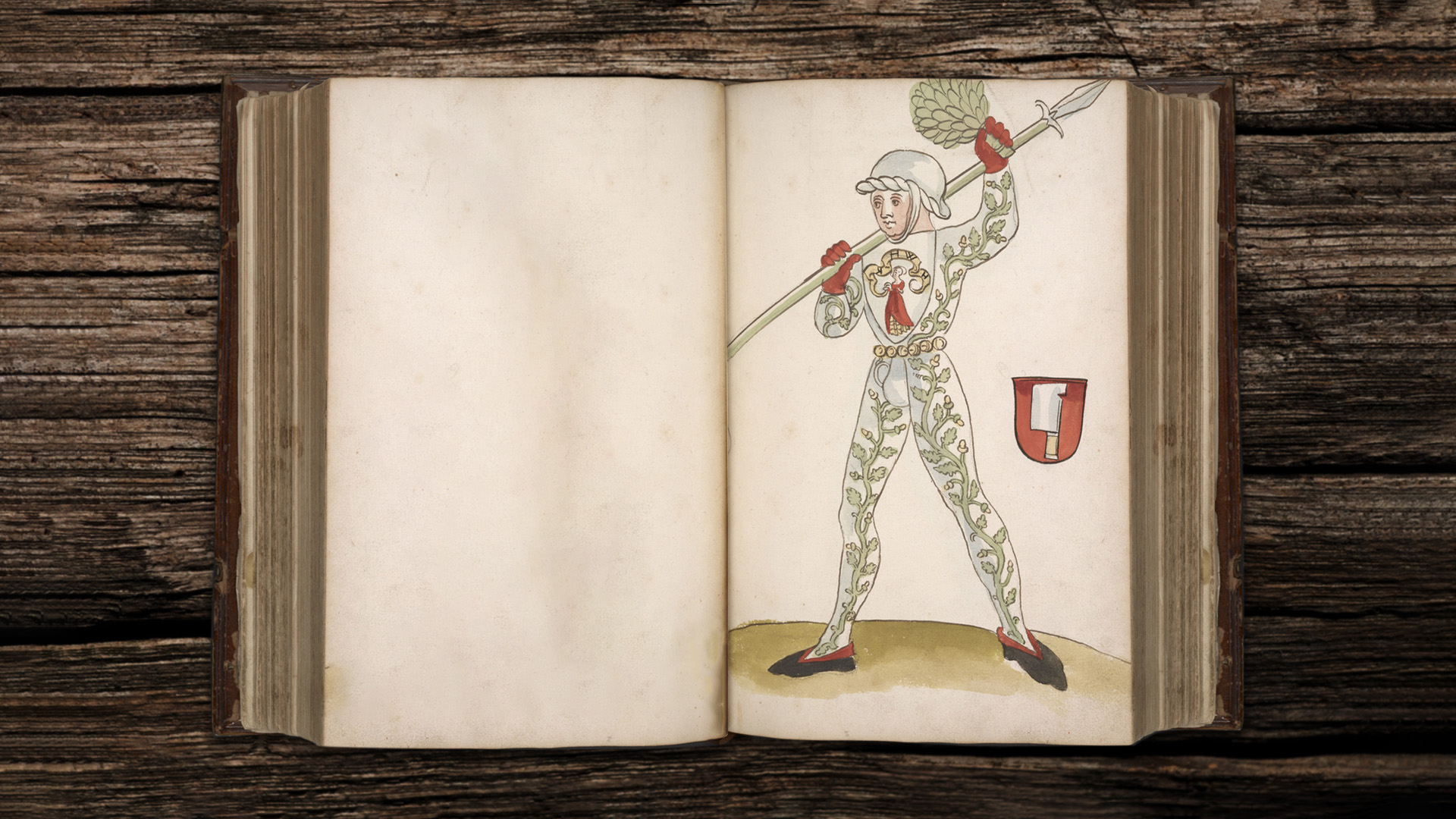

While the standard fool’s costume (increasingly seen during Fastnacht festivities at the end of the 15th century) remained unadorned, participants in decorated garments appeared for the first time from the 1450s during Nuremberg’s “Schembartlauf”, a major part of the city’s Fastnacht festivities. The costume of these “Schembart runners” changed from year to year. They wore masks with headgear in the form of helmets or hats, donned tight-fitting clothes and would bear a lance in one hand and a “Blätterboschen” in the other (a prop in which a fire tube for pyrotechnic effects was stuck). What was new about them was the decoration of their clothing with painted or appliquéd visual elements. These could be tendrils, roses, thistles, oak leaves or other (predominantly leafy) motifs. Sometimes there was also a special image on the chest of the runners – usually a full-length female figure.

Nuremberg Schembart runner1491 with oak leaf paintings and a female figure on the chest, 16th century Schembart book, Washington DC, Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection 18

‘Schembartlauf’ Garment Decorations

While the standard fool’s costume (increasingly seen during Fastnacht festivities at the end of the 15th century) remained unadorned, participants in decorated garments appeared for the first time from the 1450s during Nuremberg’s “Schembartlauf”, a major part of the city’s Fastnacht festivities. The costume of these “Schembart runners” changed from year to year. They wore masks with headgear in the form of helmets or hats, donned tight-fitting clothes and would bear a lance in one hand and a “Blätterboschen” in the other (a prop in which a fire tube for pyrotechnic effects was stuck). What was new about them was the decoration of their clothing with painted or appliquéd visual elements. These could be tendrils, roses, thistles, oak leaves or other (predominantly leafy) motifs. Sometimes there was also a special image on the chest of the runners – usually a full-length female figure.

Nuremberg Schembart runner1491 with oak leaf paintings and a female figure on the chest, 16th century Schembart book, Washington DC, Library of Congress, Rosenwald Collection 18

Day and Night as a ‘Mi-Parti’

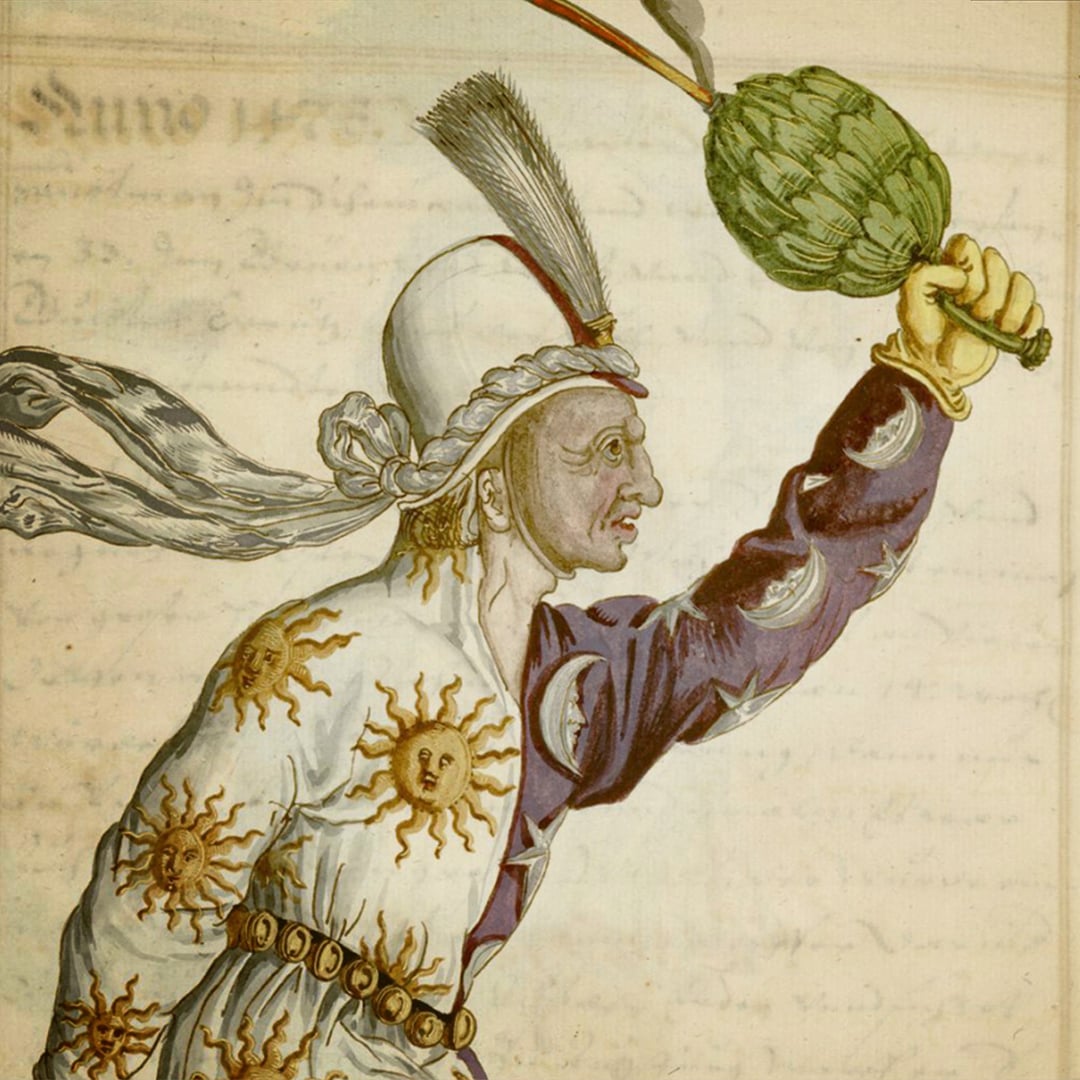

The attire of the Nuremberg “Schembart runners” was precisely documented in illustrated chronicles from their first appearance in 1449 until the “Schembartlauf” was banned in 1539, meaning that we have a good idea about what the runners looked like in each individual year they appeared. The overview of the garment paintings shows that the motifs usually did not symbolise too much. A design seen in 1472 was the exception, with the runners decorated with the sun, moon and stars. The arrangement of the stars followed the fashionable concept of the “mi-parti”, with the participants showing half of the day and half of the night on their costumes.

Schembart runner 1472 with sun, moon and stars on garment (detail), Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Day and Night as a ‘Mi-Parti’

The attire of the Nuremberg “Schembart runners” was precisely documented in illustrated chronicles from their first appearance in 1449 until the “Schembartlauf” was banned in 1539, meaning that we have a good idea about what the runners looked like in each individual year they appeared. The overview of the garment paintings shows that the motifs usually did not symbolise too much. A design seen in 1472 was the exception, with the runners decorated with the sun, moon and stars. The arrangement of the stars followed the fashionable concept of the “mi-parti”, with the participants showing half of the day and half of the night on their costumes.

Schembart runner 1472 with sun, moon and stars on garment (detail), Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Contrast of Meat and Fish

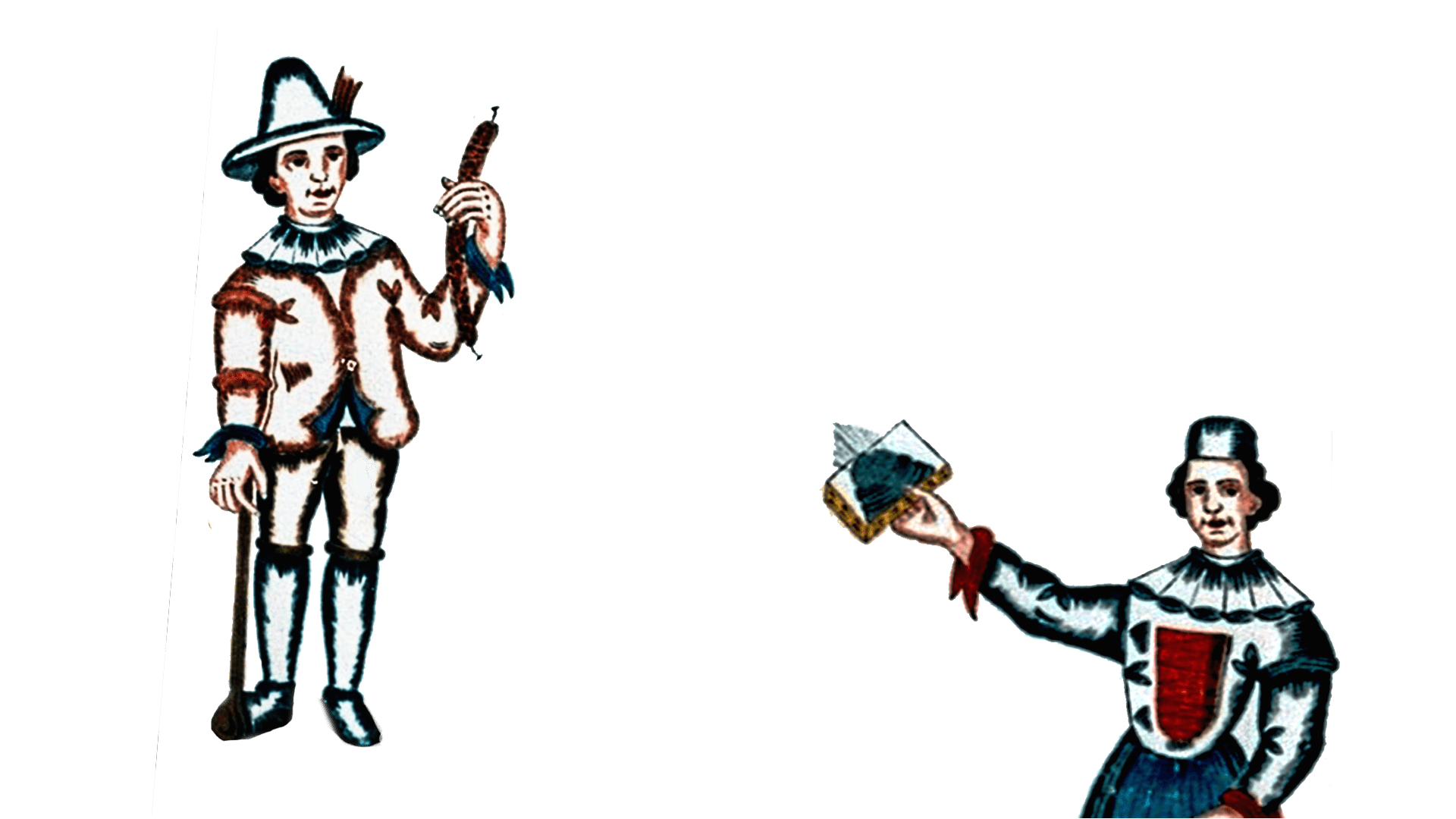

The costume design in 1515 is another example of the runners’ garments bearing decorations with a deeper symbolism. Here the runners wore a doublet – again corresponding to the “mi-parti” fashion – with fish depicted on one half and sausages appearing on the other. The fact that this combination of motifs was intended to indicate the contrast between Fastnacht and Lent was instantly obvious to late medieval observers. After the “Schembartlauf” was banned due to a Fastnacht scandal in 1539, the clothes of the runners do not seem to have had any effect as a model for later Fastnacht costumes. In any case, there is no plausible line of tradition from the “Schembart runners” to the garment paintings of the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht (which can only be attested from the 18th century onward).

Schembart runner 1515 with fish and sausages on smock (detail), Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Contrast of Meat and Fish

The costume design in 1515 is another example of the runners’ garments bearing decorations with a deeper symbolism. Here the runners wore a doublet – again corresponding to the “mi-parti” fashion – with fish depicted on one half and sausages appearing on the other. The fact that this combination of motifs was intended to indicate the contrast between Fastnacht and Lent was instantly obvious to late medieval observers. After the “Schembartlauf” was banned due to a Fastnacht scandal in 1539, the clothes of the runners do not seem to have had any effect as a model for later Fastnacht costumes. In any case, there is no plausible line of tradition from the “Schembart runners” to the garment paintings of the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht (which can only be attested from the 18th century onward).

Schembart runner 1515 with fish and sausages on smock (detail), Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

The Multicoloured Arlecchino

The first inspirations for Fastnacht garment painting in southwestern Germany probably came from Italy. The local characters of the Commedia dell ‘arte became increasingly known north of the Alps in the course of the 17th century through travelling theatre groups, and through representations of the visual arts. In particular, characters such as Pagliaccio (Bajazzo), Pulcinella or the comic servant characters from the Zanni group soon gained popularity on German stages, as well as during Fastnacht festivities. It was the Arlecchino, though, that became probably the most striking southern European figure with Fastnacht features. His external features were a black half-mask and a multicoloured garment. Due to the rarity of early depictions, it is difficult to say whether the garment got its colour from fabric applications, or whether it was partially painted. One of the oldest illustrations of an Arlecchino is from 1601.

Harlequin in a colourful patchwork garment, Tristano Martinelli title illustration, Compositions de rhétorique de Mr. Don Arlequin, 1601, Paris, Bilbiothèque Nationale

The Diamond Harlequin

Even more typical than the relatively indiscriminate colourfulness of the harlequin costume of the early period was its later division into a grid pattern with arranged coloured diamond shapes (sometimes more neat and sometimes more rough), and could be in two or more colours. The diamond pattern appeared as early as the 17th century and then eventually became the harlequin’s classic appearance. It was often portrayed in paintings, printmaking, wooden sculptures and, last but not least, porcelain products. The diamond harlequin in its classic form then seems to have soon appeared every now and then during Fastnacht festivities north of the Alps. When the first figures of this kind appeared during Fastnacht in Central Switzerland, they were described in chronicles as “Arligein” (adoption of “Harlequin” in the local dialect). They seem to have come from the Milan area and Ticino via the Gotthard.

Harlequin in a diamond pattern garment, wooden statue, coloured, 18th century, originally in the Théâtre Seraphin in the Palais-Royal, now in the Musée Carnavalet, Paris

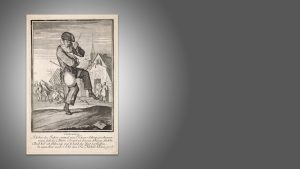

Glasses and Grills as Fabric Images

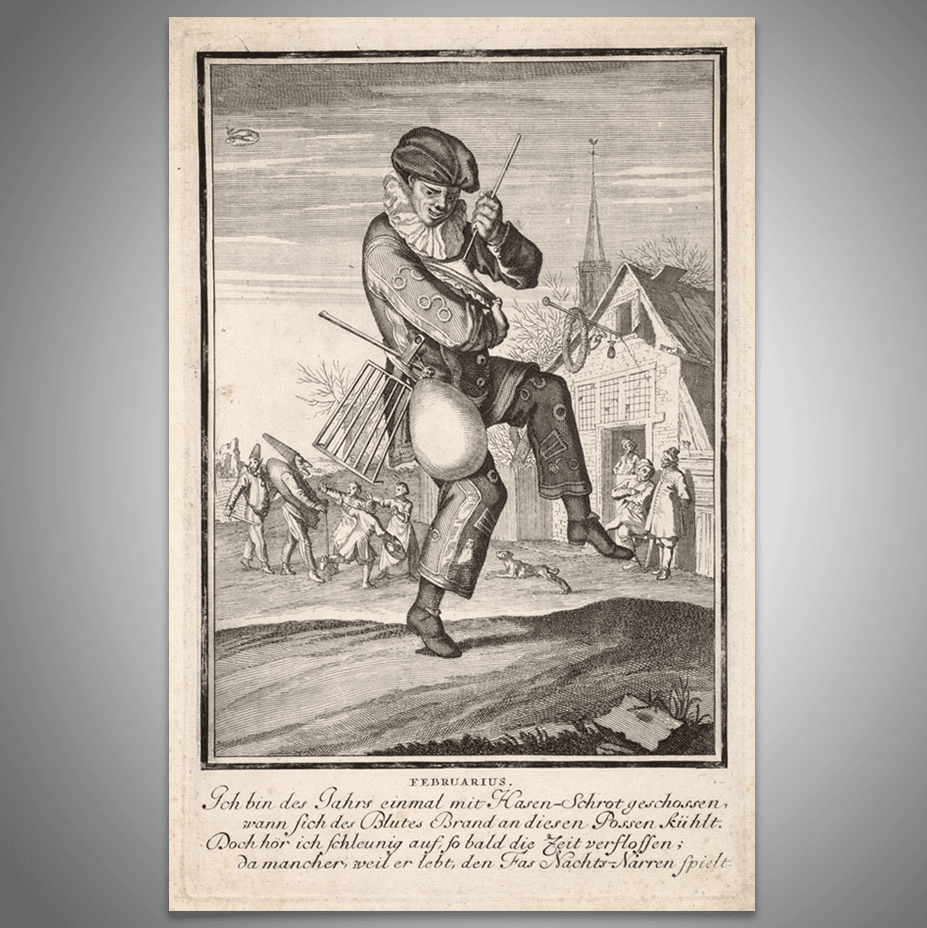

Most likely inspired by the costumes of the Italian Arlecchini, fool figures appeared during the Fastnacht festivities of the German-speaking countries in the course of the 17th century. Their garment decorations soon reached new heights. Instead of just the colourful diamond-shaped pattern, the costumes now showed simple motifs that fitted with Fastnacht and the notion of foolishness. An example of this is a print by Caspar Luyken from around 1700, designed as a picture of the month of February: A fool dressed in the new style of costume dances with a pig’s bladder and a grill on his belt, using a pot to make music in a scene in which classic Pulcinella (a type of character from the Commedia dell ‘arte) with pointed hats can be seen in the background. The main character’s smock and trousers are littered with metaphors relating to fools – predominantly glasses (a symbol of folly at the time), and a grill as a reference to the consumption of meat during Fastnacht.

“Italianised” fool with painted or appliquéd suit as picture for “February”, copper engraving by Caspar Luyken, 1698/1702, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

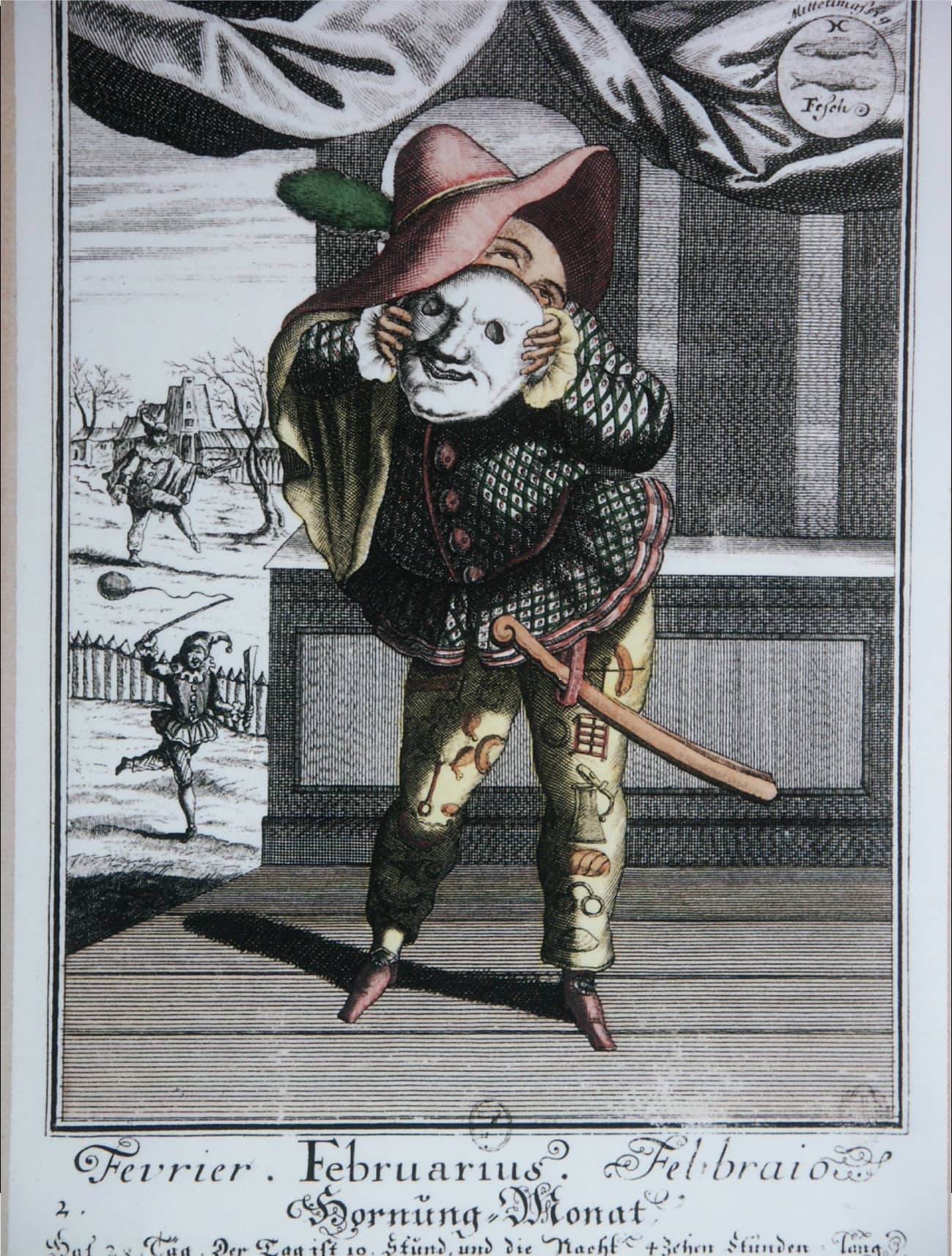

Multiplication of Motifs

Over time, the motifs on the fool’s garments became more diverse. A coloured copperplate engraving – again designed as a calendar page for the month of February – shows a chubby fool with a floppy hat, a white mask held in front of his face, a smock with diamond shapes and ornamented trousers (on which the number of objects depicted has multiplied.) In addition to glasses and a grill, a beer mug, wooden spoon, sausages, chicken drumsticks, sun, moon, stars and playing cards can all be seen. These pictorial arrangements very likely form a direct line to the painted fool’s clothes seen in the Swabian-Alemannic region, whose tradition also goes back to the 18th century – that is, there is a connection to the illustrated carnival costumes from the Commedia dell’ arte as documented in prints.

“Italianised” fool with painted or appliquéd suit as picture for “February”, coloured copper engraving, 18th century, private collection

Garment Painting Today

The paintings on the Swabian-Alemannic fool’s clothes have developed a little differently from place to place, and today the garment painters have different degrees of freedom when it comes to their design. For some, the motif repertoire is relatively open. For others, the basic patterns are largely prescribed. Essentially all parts of the garment are painted: the head piece, the smock (given it is not covered by bell straps) as well as the front and back of the trouser legs. The trouser legs in particular offer the largest painting surfaces, and are usually decorated with standing human characters or with upright animal figures. With a few exceptions, the linen garments of the “white fools” have wide-falling baroque harem trousers that are tied under the knees. Each step the wearer takes makes the painted figures move with the changing folds of the trousers, increasing the feeling of animation.

“Hansele” from Möhringen with garment paintings, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Garment Painting Today

The paintings on the Swabian-Alemannic fool’s clothes have developed a little differently from place to place, and today the garment painters have different degrees of freedom when it comes to their design. For some, the motif repertoire is relatively open. For others, the basic patterns are largely prescribed. Essentially all parts of the garment are painted: the head piece, the smock (given it is not covered by bell straps) as well as the front and back of the trouser legs. The trouser legs in particular offer the largest painting surfaces, and are usually decorated with standing human characters or with upright animal figures. With a few exceptions, the linen garments of the “white fools” have wide-falling baroque harem trousers that are tied under the knees. Each step the wearer takes makes the painted figures move with the changing folds of the trousers, increasing the feeling of animation.

“Hansele” from Möhringen with garment paintings, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Encrypted Insinuations

While the motifs of the painted fool’s garments today are noticeably clean and free of any innuendo, until well into the 19th century there were also crude, obscene and lewd depictions seen on fool’s clothes. These could be lovers in incriminating situations, as well as people defecating or throwing up. All of these objectionable motifs on individual costumes have long since been withdrawn from circulation by Fastnacht guilds. Only where certain objectionable motifs were no longer recognised as such thanks to their skilful encryption did they stop. This is the case, for example, with the standard motif on the back of the trousers of every “Narro” in Villingen. There, the popular figures of Hansel and Gretel can be seen – “Hänsele” on the left trouser leg and “Gretle” on the right trouser leg.

Painting on a garment from Villingen, “Hänsele” and “Gretle” as a standard motif on the back of the trousers of the “Villinger Narro”, photo: Narrenzunft Villingen

Hänsele with the Sausage

Gretle is seen with a comb (symbolising how she gossips about others), whilst Hänsele holds a sausage in his raised hand and offers it to Gretle. When thinking about the fact that the sausage by no means alludes only to the consumption of meat during Fastnacht – and that “sausage” has always been a common expression for “phallus” – the supposedly harmless depiction takes on a different dimension. That, too, was part of Fastnacht.

Painting on a garment from Villingen, “Hänsele” and “Gretle” as a standard motif on the back of the trousers of the “Villinger Narro”, photo: Narrenzunft Villingen, details

Harmless and Leafy Ornaments

The paintings on fool’s garments are one of the outstanding features of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities. Every “white fool” is a walking work of art thanks to the paintings on his headpiece, smock and trousers. None of the painted costumes are exactly alike. Depending on the local tradition, they may differ from each other to a small or a large degree. However, the paintings must not be completely distinctive in order to preserve the anonymity of their wearers. For example, portraits on fool’s clothes are frowned upon because they make it easier to identify the wearer, who is unrecognisable behind their mask. Modern motifs, such as characters from comics, are also considered inappropriate. Plants, tendrils, flowers and animals are permitted and encouraged, as are heraldic creatures such as lions and griffins. And then there are a number of local unique features.

“Blumennarren” from Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele

Harmless and Leafy Ornaments

The paintings on fool’s garments are one of the outstanding features of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities. Every “white fool” is a walking work of art thanks to the paintings on his headpiece, smock and trousers. None of the painted costumes are exactly alike. Depending on the local tradition, they may differ from each other to a small or a large degree. However, the paintings must not be completely distinctive in order to preserve the anonymity of their wearers. For example, portraits on fool’s clothes are frowned upon because they make it easier to identify the wearer, who is unrecognisable behind their mask. Modern motifs, such as characters from comics, are also considered inappropriate. Plants, tendrils, flowers and animals are permitted and encouraged, as are heraldic creatures such as lions and griffins. And then there are a number of local unique features.

“Blumennarren” from Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele

Headpiece of a “white fool” from Rottweil painted with Turkish motifs, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Zeitgeist on White Linen: Images of Turks

In Rottweil, traditional costumes from Tyrol as well as Turkish figures featuring on fool’s clothes have become common. The latter trend partly refers to the Turkish Wars, but also harks back to the enthusiasm of the 18th and 19th centuries for many things Turkish (as expressed, for example, in Turkish music or Turkish tea pavilions). When wearing these kinds of high-quality painted garments, the participants have to be careful: Any stains, chafing and creases in the fabric caused by sitting down can damage the works of art that are meant to last for generations (and whose time-consuming production costs a decent amount of money).

Headpiece of a “white fool” from Rottweil painted with Turkish motifs, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Zeitgeist on White Linen: Images of Turks

In Rottweil, traditional costumes from Tyrol as well as Turkish figures featuring on fool’s clothes have become common. The latter trend partly refers to the Turkish Wars, but also harks back to the enthusiasm of the 18th and 19th centuries for many things Turkish (as expressed, for example, in Turkish music or Turkish tea pavilions). When wearing these kinds of high-quality painted garments, the participants have to be careful: Any stains, chafing and creases in the fabric caused by sitting down can damage the works of art that are meant to last for generations (and whose time-consuming production costs a decent amount of money).

Headpiece of a “white fool” from Rottweil painted with Turkish motifs, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de