Fool and Death

Beginning of all Foolishness: Denial of God

The oldest depictions of fools in the visual arts come from an entirely non-Fastnacht context: They appear in Psalm manuscripts, and always at the beginning of Psalm 52 (in the Latin version; Psalm 53 in the Greek version), where it says: “The fool said in his heart: There is no God.” According to medieval understanding, this worst conceivable sacrilege, the denial of God, was the core of all foolishness at that time. Those who lacked the knowledge of the Creator’s omnipotence and the fear of the Lord, as foolish jesters did, were considered doomed and consigned to eternal death after their life on Earth had ended. The miniature painters who illustrated the Psalm manuscripts – “illuminated”, as it is called in the technical jargon – tried to express this, sometimes quite drastically, at the beginning of Psalm 52.

Fool with the devil, beginning of Psalm 52, Psalter manuscript, illuminated by Jean de Mandeville, France, circa 1350/1360, Los Angeles, Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 1, v1 (84.MA.40.1), fol. 284

The Fool under the Devil’s Spell

In this French psaltery, illuminated around 1350/60 by Jean de Mandeville, the artist shows that it is none other than the devil himself who makes the fool ignorant of God. As a horned demon in a coat of fur and with goat’s feet hovering over him, the prince of hell blinds the “insipiens”, the “unwise”, who can be seen equipped with a staff and consuming a loaf of bread. In this way the jester represents, from the very start, the epitome of human aberration and sinfulness. If he does not take the last-minute opportunity for repentance and a radical change of heart – called “metanoia” in Greek – he will inevitably consign himself to perpetual damnation.

Fool with the devil, beginning of Psalm 52, Psalter manuscript, illuminated by Jean de Mandeville, France, circa 1350/1360, Los Angeles, Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 1, v1 (84.MA.40.1), fol. 284 (detail)

Punishable Contempt for God

The image of the fool as God’s ignoramus, as projected by the theology of the high Middle Ages, persisted unchanged at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. When Sebastian Brant published his famous book “Ship of Fools” in 1494, in which he interpreted all the disturbing developments of his time as expressions of rapidly increasing foolishness and progressive estrangement from God, he explicitly gave one chapter the heading “from contempt of God”. The accompanying woodcut shows a jester brazenly grabbing God the Father’s beard, causing a hail of stones to hit him from the sky. “Grab the Lord by the beard” was an established expression at that time, which meant something along the lines of “slander God” or even “despise God”.

Fool grasping God the Father by the beard, woodcut for Chapter 86, “contempt of God”, from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Punishable Contempt for God

The image of the fool as God’s ignoramus, as projected by the theology of the high Middle Ages, persisted unchanged at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. When Sebastian Brant published his famous book “Ship of Fools” in 1494, in which he interpreted all the disturbing developments of his time as expressions of rapidly increasing foolishness and progressive estrangement from God, he explicitly gave one chapter the heading “from contempt of God”. The accompanying woodcut shows a jester brazenly grabbing God the Father’s beard, causing a hail of stones to hit him from the sky. “Grab the Lord by the beard” was an established expression at that time, which meant something along the lines of “slander God” or even “despise God”.

Fool grasping God the Father by the beard, woodcut for Chapter 86, “contempt of God”, from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Foolishness in the Mother’s Milk

In the same historical context of the lack of knowledge of God, there is a carving on the side of a church pew in the Heiligkreuzmünster in Rottweil, southern Germany, which was created in 1703 but goes back to a picture arch from the 16th century. It shows a laughing mother jester feeding her crying child a spoonful of jester’s food. Against the backdrop of the original idea of the fool, this is not, as has long been assumed, a humorous depiction that has strayed into the church. Instead, it is a profoundly tragic image of the imperfection and sinfulness that are inherent in every human being. “Foolishness gets everyone during their first porridge” was a proverb of the late Middle Ages. Here, it gets the picture.

Mother jester with child, carving on a church chair cheek, circa 1703, Rottweil, Heiligkreuzmünster

Mother jester, individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Laufenburg/Hochrhein, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

The Mother of the Fools as a Figure of Tradition

The figure of the mother jester also plays a prominent role in traditional Fastnacht customs. She appears as an important figure on her own in Laufenburg along the High Rhine, for example, and differs from the other “Narrones” – the plural of “Narro” (“fool”, “jester”) in the local dialect – and their masculine-looking masks by donning a slightly smiling feminine polished face mask. Her special position as “genetrix stultitiae”, as “bearer of all foolishness”, is expressed in Laufenburg Fastnacht tradition to this day in the fact that her dress and mask may not be worn by any regular guild member. Instead, they can only be worn by a friend of the guild – that is, an outsider. In the German-Swiss twin city, people prefer to keep their distance from the mother of foolishness, the source of all the dangers of being human.

Mother jester, individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Laufenburg/Hochrhein, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

The Mother of the Fools as a Figure of Tradition

The figure of the mother jester also plays a prominent role in traditional Fastnacht customs. She appears as an important figure on her own in Laufenburg along the High Rhine, for example, and differs from the other “Narrones” – the plural of “Narro” (“fool”, “jester”) in the local dialect – and their masculine-looking masks by donning a slightly smiling feminine polished face mask. Her special position as “genetrix stultitiae”, as “bearer of all foolishness”, is expressed in Laufenburg Fastnacht tradition to this day in the fact that her dress and mask may not be worn by any regular guild member. Instead, they can only be worn by a friend of the guild – that is, an outsider. In the German-Swiss twin city, people prefer to keep their distance from the mother of foolishness, the source of all the dangers of being human.

Mother jester, individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Laufenburg/Hochrhein, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

The Foolish Mother and her Seven Sons

A study of various representations of the mother jester could be a chapter all of its own. The increasing differentiation of the motif in the early modern period is illustrated by a detail from an ornamental plate made in Augsburg in 1528, which, in its entirety, shows the whole spectrum of the idea of the foolishness at the time. A mother jester appears in the middle on the bottom of the plate, surrounded by her seven sons. The number seven is no coincidence, something that is still proven today by vivid jester-related phrases like in Rottweil: “Narro, siebe Sih, siebe Sih sind Narro gsi” or in Constance: “Narro, Narro, siebe siebe, siebe Narre sind es gsi” (both meaning something along the basic lines of “the fool and the seven sons”). What is meant by this and whether it is possibly alluding to the inverted gifts of the Holy Spirit, or even to the seven deadly sins, can only be speculated. But the fact that the mother jester as the person responsible for all the shortcomings of her offspring, is theologically close to the figure Eve is an obvious thought.

Mother jester with her seven sons, detail of an ornamental plate featuring scenes of fools, Augsburg 1528, school of Jörg Breu the Elder, Innsbruck, Ambras Castle, Inv. No. P 4955 (detail)

Foolishness and Original Sin

Foolishness as an expression of remoteness from God was ultimately synonymous with every form of sinfulness, which suggests the comparison of the figure of the mother jester with the biblical figure of Eve, and the original sin that came into the world through her. Anyone who might still be sceptical about this comparison at first glance is proven wrong by a French woodcut from around 1500. Created for a booklet by the Flemish humanist Jodocus Badius, which further developed the “Ship of Fools” theme. In the depiction in question, the Fall of Man takes place with Adam and Eve on a ship of fools, rowed by two horned devils wearing jester’s caps. And the text explains that “Eve, our original mother, is the mother of all foolishness”. With this, foolishness and original sin are definitively set on the same level.

Eva during the Fall of Man in the Ship of Fools, woodcut from Josse Bade: “La grant nef des folles selon les cinq cens de nature, composée selon l’évangile du Monseigneur Mathieu”, Paris, circa 1500, Paris, Biliothèque Nationale, In-4 °, Rés. M. Yc. 750

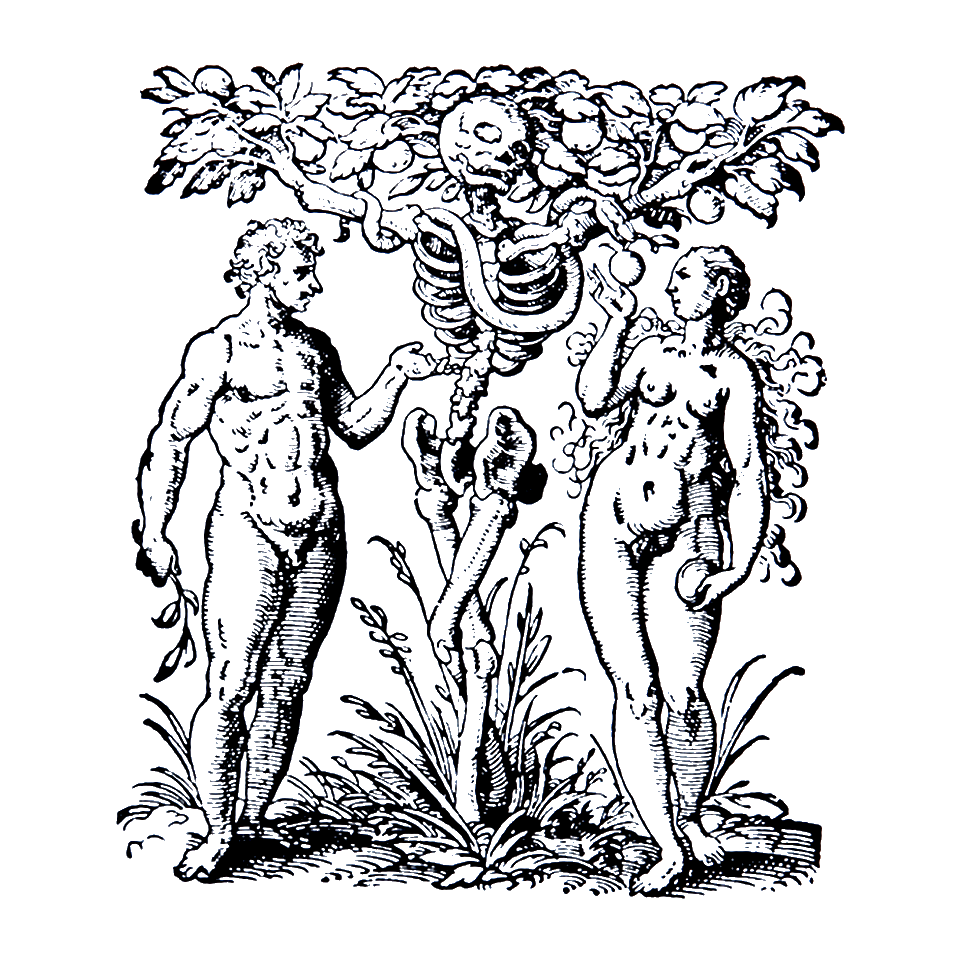

Death as Sin’s Wage

Death entered the world through the Fall of Eve. According to Genesis 3:3, God warns the first humans against eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge: “Do not eat of it … or you will die”. The serpent of seduction, on the other hand, says to Eve: “As soon as you eat of it … you will be like God” (Genesis 3:5). By ultimately following the serpent rather than God, Adam and Eve lose not only paradise, but also their immortality. This is how the Old Testament explains the two great mysteries of human existence: Man’s imperfection and, above all, the temporal limitedness of his existence. This causation of the Fall for death as a condition of life is visualised very clearly in a woodcut from 1533, in that it depicts the tree of knowledge itself as the personification of death. If original sin is the reason for death and if – as can be concluded – foolishness has the same meaning as original sin, then ultimately foolishness should also have a causal connection with death. And that was precisely what people were convinced of in the late Middle Ages.

Tree of knowledge in the form of a skeleton, woodcut title for Jacob Ruef’s “Alle Heimlichkeit des weiblichen Geschlechts”, Frankfurt/M. 1533

Death catches the Fool

The closeness of the jester to death, a strange idea today but a common one in the late Middle Ages, was the subject of many visual depictions. A woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, for example, shows how death catches up with the fool by surprise. While the fool has just gone along his way without a worry, death, already with the stretcher on his shoulders, suddenly grabs him from behind by the garment and orders: “You stay”. An image that, at first glance, seems to have nothing to do with the role of the jester during Fastnacht. But Fastnacht, as we will see, is much more closely related to death and mortality than we are aware of today.

Fool surprised by death, woodcut for Chapter 85, “Nit fursehen den dot”, from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Death catches the Fool

The closeness of the jester to death, a strange idea today but a common one in the late Middle Ages, was the subject of many visual depictions. A woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, for example, shows how death catches up with the fool by surprise. While the fool has just gone along his way without a worry, death, already with the stretcher on his shoulders, suddenly grabs him from behind by the garment and orders: “You stay”. An image that, at first glance, seems to have nothing to do with the role of the jester during Fastnacht. But Fastnacht, as we will see, is much more closely related to death and mortality than we are aware of today.

Fool surprised by death, woodcut for Chapter 85, “Nit fursehen den dot”, from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

The Fool and Death in the Dance of Death

The relationship between the fool and death in the Grossbasel Dance of Death from the 15th century appears to be a kind of kinship. This monumental fresco on a cemetery wall, demolished in 1805, followed a type of image common in the late Middle Ages: In a large stand revue, death is shown taking people of all ranks and leaving no one behind. One detail of the fool and death relationship is particularly interesting: Death, who comes to fetch the jester, is himself wearing a jester’s garment with a jingling cap and a jingling ring in his hand, while the jester follows him with his marotte lowered. Johann Rudolf Feyerabend, who had captured the ghoulish work of art visually before it was destroyed, shows the colourfulness of the scene in his watercolour copies from 1806.

Grossbasel Dance of Death, 15th century, detail, watercolour copy of the original by Johann Rudolf Feyerabend (destroyed in 1805), 1806, Basel, Historisches Museum

Death in the Jester’s Garment

Johann Rudolf Feyerabend’s work meant that, above all, the colours were able to be documented. However, copperplate copies by Matthäus Merian from 1621 (almost two centuries older than Feyerabend’s work) document in even more detail the jester and death of the Basel Dance of Death, destroyed in 1805. The jester’s face-down marotte shows, in a way formerly common in visual symbolism, that his mortal power has been extinguished. Even today, for example, the funeral ritual for bishops includes carrying the bishop’s crook with the point down behind the coffin in the funeral procession.

Fool and death in the Grossbasel Dance of Death, 15th century, copper engraving copy by Matthäus Merian, 1621, in: “Todten Tanz …”, Frankfurt/M 1725

The Fool as Death – Death as the Fool

While we can still assume that the fool is parodied by death during the Grossbasel Dance of Death, the fool and death figures are seen fully merged in two prints by Hans Sebald Beham from 1540 and 1541. The earlier sheet, an etching, shows the well-known motif “Jester and the Maiden”. The jester seems to surprise the young woman and presents her with flowers. In the later sheet, an engraving, almost the same motif appears again, but two details have changed considerably: The jester is now death wearing a jester’s cap, with hands over an hourglass instead of flowers. And the motto reads: “Omnem in hominem venustatem mors abolet” (“All beauty in man is made to perish by death”). This highly interesting sequence of images makes it clear that, according to the view of the time, the fool is ultimately none other than death itself. He hasn’t actually transformed at all in the second picture. He has simply unmasked himself.

Jester and the Maiden, etching by Hans Sebald Beham, 1540, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, STN 614 / Death in a jester’s garment with maiden, copper engraving by Hans Sebald Beham, 1541, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, RP-P-H-1041

Fool and Death in the same Role

The depiction of the close relationship between the symbolic figures of the fool and death is repeated constantly in the visual arts at the turn of the Middle Ages and the modern era. In 1516, for example, Ambrosius Holbein painted the motif “Jester and the Maiden” on one side and “Death and the Maiden” on the other of a window niche facing each other in the monastery of St. Georgen in Stein am Rhein, Switzerland. The fact that the two frescoes are conceived as counterparts is, of course, no coincidence.

Death and the Maiden / Jester and the Maiden, opposing frescoes in a window niche by Ambrosius Holbein, 1516, Stein am Rhein, Kloster Sankt Georgen, Saal des Abtes David von Winkelsheim, photos: Werner Mezger

Two Heads – One Message

In the carvings on choir stalls, the jester and death also frequently correlate with each other as counterparts. This is also the case with the choir stalls of the parish church of St. George in Nördlingen, Bavaria, which were created around 1500 in the workshop of the local artist Hans Tauberschmid. The similarity in content and meaning of the two symbolic figures of the fool and death was therefore generally known, and apparently a popular concept.

Jester’s head and skull (counterparts), carvings on the choir stalls of the parish church of St. George in Nördlingen, workshop of Hans Tauberschmid, circa 1500, photos: Werner Mezger

Fool and Death – Set in Stone

At least as common as the corresponding placement of the jester and death on choir stalls in late Gothic sacred buildings was their deliberate proximity high above the church visitors as vault consoles. One example among many is the collegiate church of Öhringen in Hohenlohe, near Stuttgart, where a stonemason finished one vault rib of the central nave with a skull and a second one of the slightly lower southern aisle with a jester’s head – both, again, on the same column.

Jester’s head and skull as counterparts, console sculptures at the end of the 15th century on the same column in the collegiate church of Öhringen / Hohenlohe, photos: Werner Mezger

Devil, Fool and Death as a Trinity

The design of the vault consoles in the south nave of the Heiligkreuzmünster in Rottweil provides a brief summary of the idea of the fool. In 1497, only three years after Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, a stonemason created the following constellation of figurative vault consoles: In the second-last side chapel, he placed a winged devil with a convex mirror and a bagpipe-playing jester with a dog as counterparts, and in the last side chapel, similar to the jester of the preceding chapel, a grinning skull with the inscription “Memento mori”. From these three adjacent vault consoles, everyone could see where foolishness comes from – the devil – and where it leads to: death.

Devil, fool and death, three console sculptures from 1496/97 in the vault of the Heiligkreuzmünster in Rottweil, photos: Oswin Angst

Two “Schuttige”, main figures during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolish Devils during Fastnacht

The connection between the devil, the fool and death is still easily recognisable in the traditional customs of some Fastnacht towns that have a long tradition. For example, the defining jester types of Elzach near Freiburg in southern Germany (what are known locally as “Schuttige”) still clearly retain devil-like features with their terrifying masks and their wild appearance. One striking individual figure among them – donning a black garment, horned face mask and a three-pronged fork in his hand – even represents the devil himself.

Two “Schuttige”, main figures during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolish Devils during Fastnacht

The connection between the devil, the fool and death is still easily recognisable in the traditional customs of some Fastnacht towns that have a long tradition. For example, the defining jester types of Elzach near Freiburg in southern Germany (what are known locally as “Schuttige”) still clearly retain devil-like features with their terrifying masks and their wild appearance. One striking individual figure among them – donning a black garment, horned face mask and a three-pronged fork in his hand – even represents the devil himself.

Two “Schuttige”, main figures during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

“Totengfriss”, an individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Death as the Devil’s Fool

The demonic and the morbid go hand in hand: The scariest sight during the Elzach Fastnacht is what is known as the “Totengfriss”. However, death as a Fastnacht figure is nothing out of the ordinary. On the contrary: It is fully in keeping with the ancient idea of the fool and, on top of that, affirms the course of the liturgical year. The affinity between the jester and death finds its major parallel in the immediate proximity of Fastnacht and Ash Wednesday: The appearance of the jesters during Fastnacht is followed by Ash Wednesday, the day in the church year when death is remembered more vividly than on any other. It is precisely that thought that is echoed in the foolishness of Fastnacht.

“Totengfriss”, an individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Death as the Devil’s Fool

The demonic and the morbid go hand in hand: The scariest sight during the Elzach Fastnacht is what is known as the “Totengfriss”. However, death as a Fastnacht figure is nothing out of the ordinary. On the contrary: It is fully in keeping with the ancient idea of the fool and, on top of that, affirms the course of the liturgical year. The affinity between the jester and death finds its major parallel in the immediate proximity of Fastnacht and Ash Wednesday: The appearance of the jesters during Fastnacht is followed by Ash Wednesday, the day in the church year when death is remembered more vividly than on any other. It is precisely that thought that is echoed in the foolishness of Fastnacht.

“Totengfriss”, an individual figure during Fastnacht festivities in Elzach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Foolishness Finishes: Memento mori

Ash Wednesday takes its name from the rite of the sprinkling of ashes: When the cross is drawn on the forehead of churchgoers, the priest declares: “Memento homo quia pulvis es et ad pulverem reverteris” (“Remember man, that you are dust, and to dust you shall return”). This emphatic reminder of the mortality of humankind on the day after Fastnacht marks the beginning of the tension in the liturgical year that leads to the message of Resurrection at Easter upon the end of Lent. If we remember the multiple links between the idea of death and the motif of the fool in the visual arts of the 15th and 16th centuries, the memento mori of the beginning of Lent was already inherent in Fastnacht, according to late medieval understanding.

The Church rite of the ash cross on Ash Wednesday. Photo: Werner Peschke

Foolishness Finishes: Memento mori

Ash Wednesday takes its name from the rite of the sprinkling of ashes: When the cross is drawn on the forehead of churchgoers, the priest declares: “Memento homo quia pulvis es et ad pulverem reverteris” (“Remember man, that you are dust, and to dust you shall return”). This emphatic reminder of the mortality of humankind on the day after Fastnacht marks the beginning of the tension in the liturgical year that leads to the message of Resurrection at Easter upon the end of Lent. If we remember the multiple links between the idea of death and the motif of the fool in the visual arts of the 15th and 16th centuries, the memento mori of the beginning of Lent was already inherent in Fastnacht, according to late medieval understanding.

The Church rite of the ash cross on Ash Wednesday. Photo: Werner Peschke

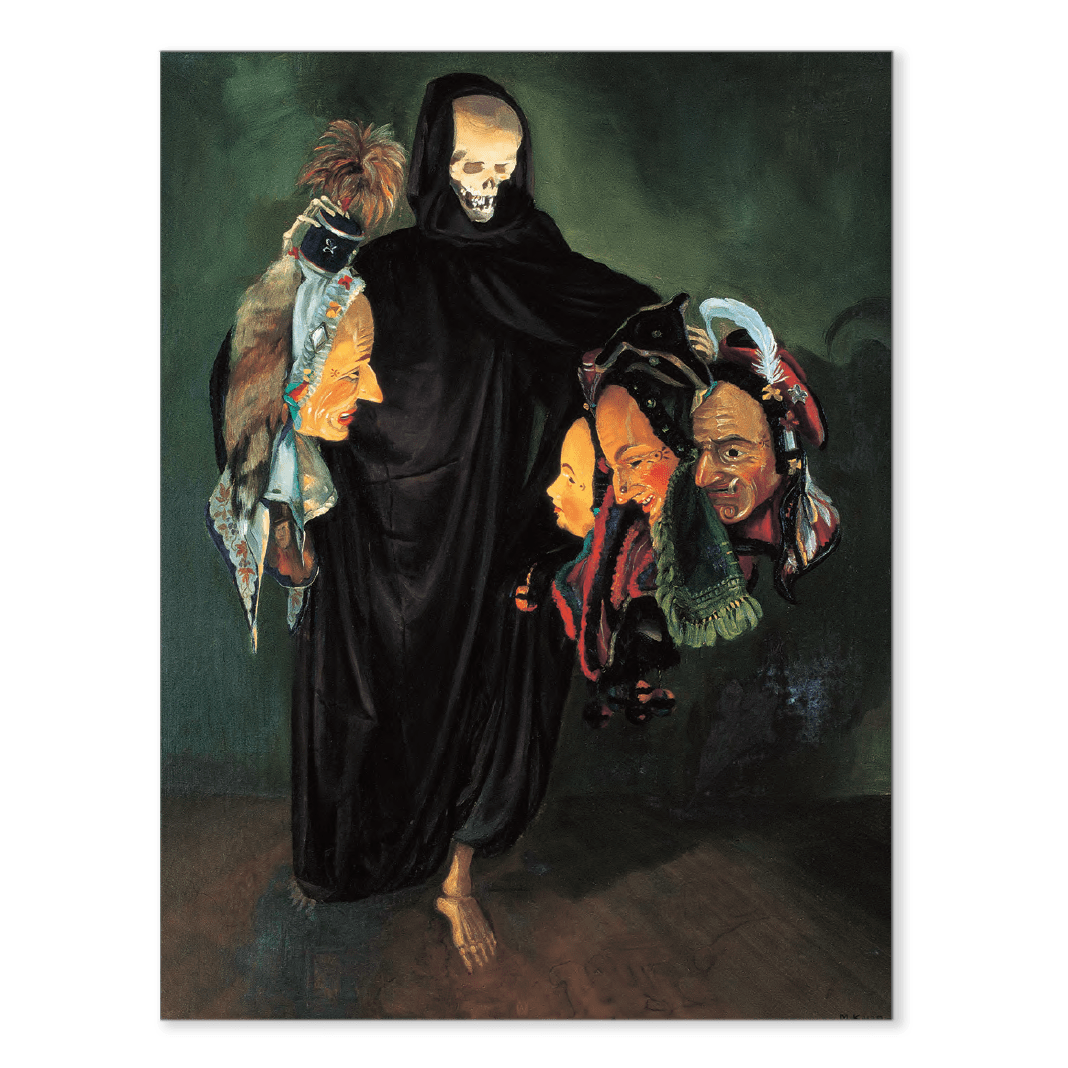

Ash Wednesday

Without explicitly knowing the historical context, or even the theory of the idea of the fool, the Rottweil artist Maria Kopp-Gössele painted a picture in 1954 entitled “Ash Wednesday”, in which death takes the jester’s Fastnacht face mask. What was probably created intuitively in the wake of the Second World War, which was less than ten years before then, does profound justice to the essence of the Fastnacht festivities against the background of today’s cultural-historical knowledge.

Ash Wednesday, painting by Maria Kopp-Gössele, 1954, Rottweil, Stadtmuseum