Devil and Fool

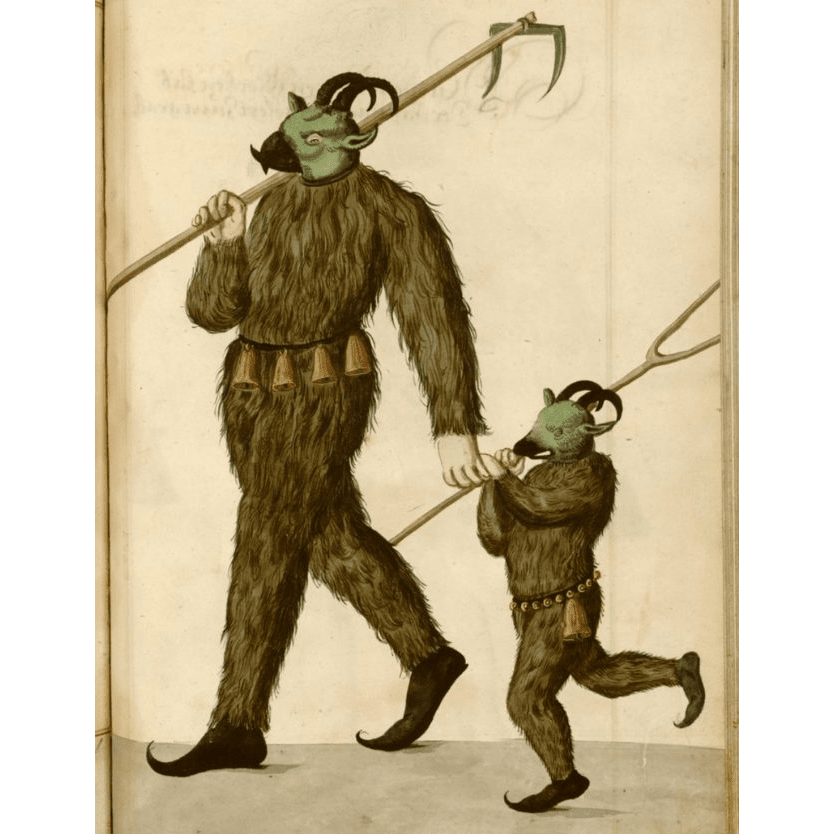

Oldest Fastnacht Figures: Devils

Around 1400, the Church increasingly began to evaluate the contrast between Fastnacht an Lent. Referring to the church teacher Aurelius Augustinus, who sharply distinguished the “civitas Dei” (the State of God) from the “civitas diaboli” (the State of the Devil), the theologians applied this model to the relationship between Lent and Fastnacht: People live religiously during Lent (as preached above all by Franciscan and Dominican monks), whilst in contrast the devil is let loose during Fastnacht. This “demonisation” of Fastnacht from the pulpits was soon reflected in Fastnacht costumes. That is why devils were among the oldest masked figures worn during the festivities. A depiction from the Nuremberg Fastnacht from the 15th century shows two of these devil-like creatures with animal heads, horns, skins and forks.

Large and small devil in the Nuremberg Schembart run, Schembart manuscript from the Pickert collection. 16th century, Nuremberg, Stadtbibliothek Nor. K. 444m fol. 25 v.

Demon Masks from Processions

The devil disguises were not primarily made for Fastnacht. Rather, they were needed for church processions, which in the late Middle Ages, especially during Corpus Christi, were large mobile spiritual spectacles where living images from salvation history were shown – from scenes from the life of Christ, through to angels and saints, down to devils and demons. We know from urban archaeology what their masks looked like: In 1996, a fragment of a 15th century devil face mask modelled in clay was found in Ulm, which can now be seen along with a reconstruction in the Archaeological State Museum in Constance, Germany. There is no doubt it was used for processions. Once a year, however, these devil masks were allowed to be borrowed from Church prop rooms and worn on their own, as it were – during Fastnacht, when “the devil was on the loose”. Council minutes from several towns document very precisely how they were leased.

Fragment of a devil’s mask from Ulm with reconstruction, clay with remains of the original polychrome version, late 15th century, Constance, Archäologisches Landesmuseum

Demon Masks from Processions

The devil disguises were not primarily made for Fastnacht. Rather, they were needed for church processions, which in the late Middle Ages, especially during Corpus Christi, were large mobile spiritual spectacles where living images from salvation history were shown – from scenes from the life of Christ, through to angels and saints, down to devils and demons. We know from urban archaeology what their masks looked like: In 1996, a fragment of a 15th century devil face mask modelled in clay was found in Ulm, which can now be seen along with a reconstruction in the Archaeological State Museum in Constance, Germany. There is no doubt it was used for processions. Once a year, however, these devil masks were allowed to be borrowed from Church prop rooms and worn on their own, as it were – during Fastnacht, when “the devil was on the loose”. Council minutes from several towns document very precisely how they were leased.

Fragment of a devil’s mask from Ulm with reconstruction, clay with remains of the original polychrome version, late 15th century, Constance, Archäologisches Landesmuseum

Devil as the oldest type of figure during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, Wilflingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Fastnacht Devil: Unchanged for Centuries

In the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht, devil figures based on the classical iconography of the late Middle Ages (featuring horns, skins, black faces, bared teeth and forks) have survived to this day. A good example of this is the devil from Wilflingen, on the southern edge of the Swabian Alb. He looks just like he did in 15th century and, with his face mask now being carved from wood, dates back in this form to well before 1800.

Devil as the oldest type of figure during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, Wilflingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Bräunlinger “Stadthansel” with classic polished face masks, Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Enigmatic Beauty: Polished Face Masks

Much more widespread than the devil face masks are the bright, friendly smiling masks – which come across rather feminine and almost a little seductive with their pointed mouths. One of the core areas of these “Glattlarven” (polished face masks) is, above all, the Baar – the landscape surrounding the origin of the Danube. Examples of this are the “Stadthansel” from Bräunlingen, in the German federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. However, these polished face masks are by no means limited to south-western Germany. They also exist in almost identical form in Tyrol, Trentino, Upper Italy and even Sardinia. At first glance, this type of mask seems to have nothing to do with any devil figures.

Bräunlinger “Stadthansel” with classic polished face masks, Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Enigmatic Beauty: Polished Face Masks

Much more widespread than the devil face masks are the bright, friendly smiling masks – which come across rather feminine and almost a little seductive with their pointed mouths. One of the core areas of these “Glattlarven” (polished face masks) is, above all, the Baar – the landscape surrounding the origin of the Danube. Examples of this are the “Stadthansel” from Bräunlingen, in the German federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. However, these polished face masks are by no means limited to south-western Germany. They also exist in almost identical form in Tyrol, Trentino, Upper Italy and even Sardinia. At first glance, this type of mask seems to have nothing to do with any devil figures.

Bräunlinger “Stadthansel” with classic polished face masks, Bräunlingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

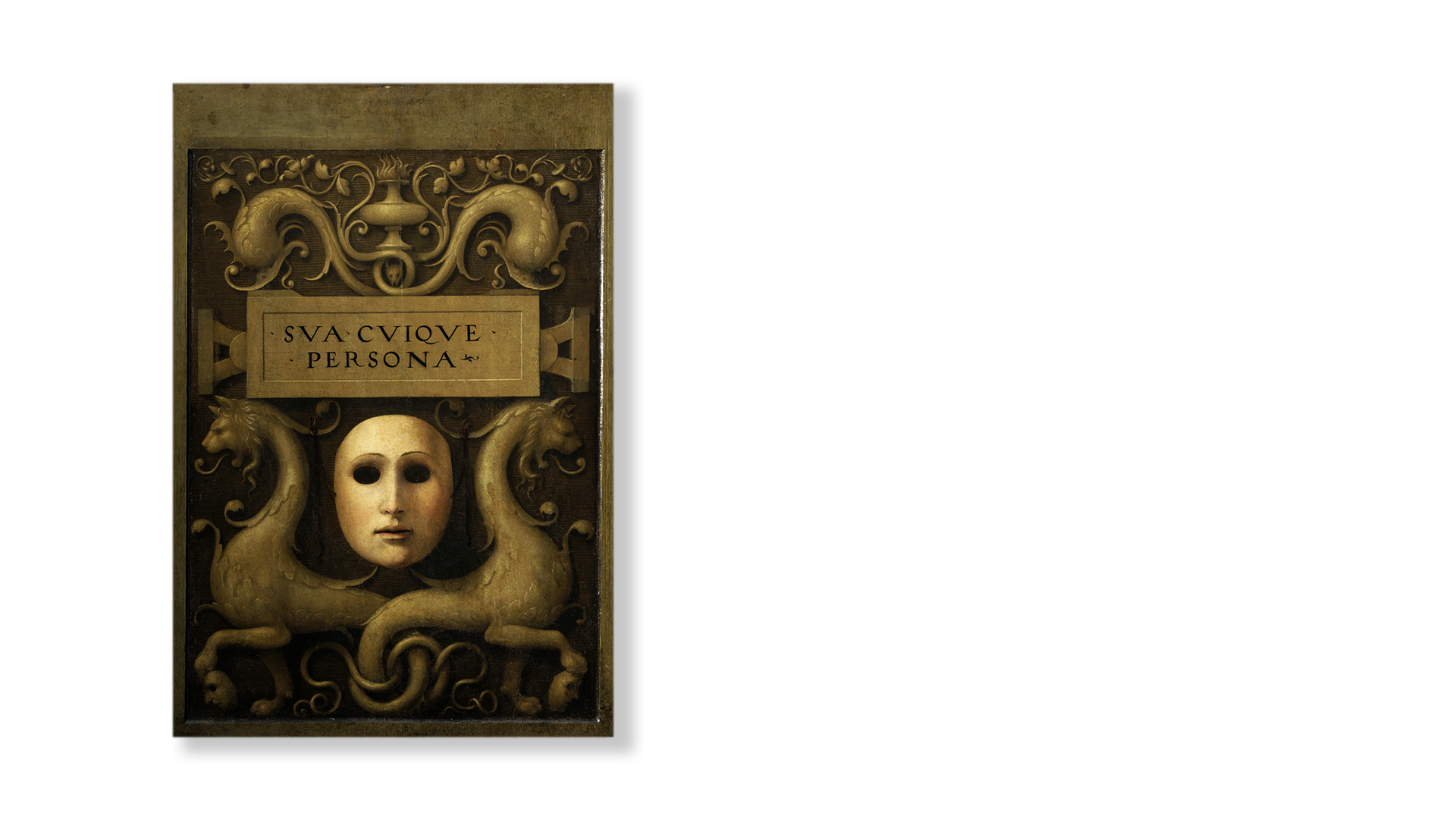

Mediterranean Origin

In German Fastnacht research, the opinion prevailed for a long time that the polished face mask had its origins in the Baroque, and that it was developed in the 17th or 18th century by wood sculptors who also carved putti for church buildings. It is now known, however, that this type of mask is much older, and has its origins in Italy. For example, a painting made around or shortly after 1500, and which can be viewed in the Uffizi in Florence, shows a polished face mask that differs from later examples only in the slightly larger eye openings. The Latin inscription “SVA CVIQVE PERSONA” means: “Everyone is their own mask”. Further research shows that this type of mask was already known in the Sardinian region before 1500.

Renaissance mask, circa 1500/10, painted wooden cover for the portrait of a woman “La Monaca” by Giuliano Bugiardini or Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Florence, Uffizi Gallery

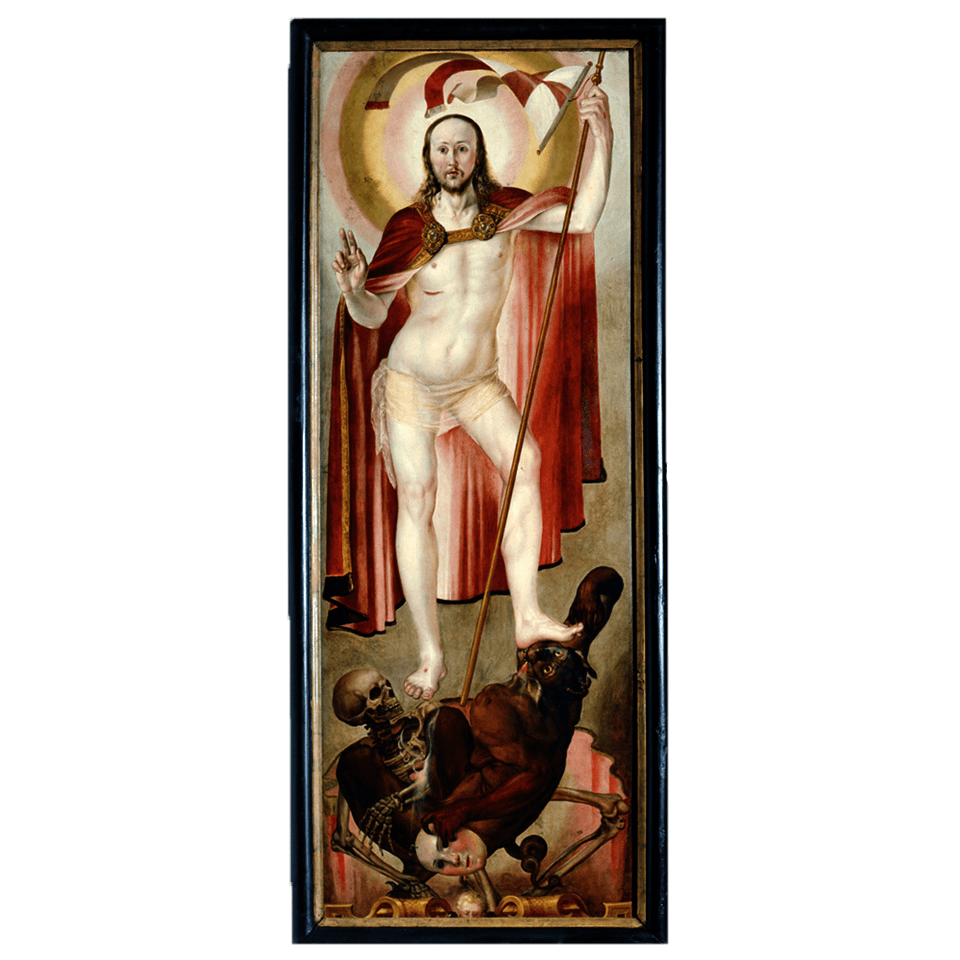

The Devil’s Disguise Mask

A key piece of evidence for the early adoption of the polished face mask north of the Alps is a panel painting created around 1545/50 by the Munich painter Hans Mielich for the tomb of the patrician Liegsalz family in the Frauenkirche in Munich. It shows the resurrected Christ triumphing over death and the devil. Death can be seen already sinking back, but the devil continues to fight, holding an immaculately beautiful, wood-carved and colourful polished face mask in his left hand – the exact same type which could still be worn during Fastnacht today.

Resurrected Christ conquering death and the devil, central panel by Hans Mielich, circa 1545/50, Munich, Frauenkirche, photo: von der Mülbe

Friendly Mask as an Illusion

Hans Mielich had taken a trip to Italy shortly before painting this picture. From here, it appears he then took this motif back with him to the northern side of the Alps. The insight gained from this image is crucial. Although, at first glance, it has no demonic features, gaps can be seen opening up behind the polished face mask.: Behind it, none other than the devil himself hides his true appearance. As such, the basic idea of the masks’ devilish nature is omnipresent.

Resurrected Christ conquering death and the devil (detail), central panel by Hans Mielich, circa 1545/50, Munich, Frauenkirche, photo: von der Mülbe

Hidden Laugher: The Fool

Alongside the devils known from the processions and the elegantly masked deceivers (behind whom the devil was ultimately also to be found), at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries one type of figure increasingly made its mark as a Fastnacht figure, eventually outnumbering all other masked figures and becoming the true representative of the festivities themselves: the fool. As this Dutch portrait of a fool looking through his fingers from around 1500 shows, his standard costume included a two-coloured garment, a hooded headdress with donkey ears and an insinuated cockscomb, as well as a peculiar sceptre crowned with a head. The fact that the grimacing, laughing fool depicted here is still wearing glasses in his hand is meant to underline his simplicity.

Laughing fool looking through the fingers, painting by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen (credited), circa 1500, Wellesley USA, Davis Museum at Wellesley College

Biblical Origin of the Fool

The earliest visual depictions of fools that we know of initially had nothing at all to do with Fastnacht. They appear, from the 13th century onwards, in a theological context – namely in Psalm manuscripts at the beginning of Psalm 52 (in the Latin version; Psalm 53 in the Greek version), which begins with the words: “Dixit insipiens in corde suo: Non est Deus” (“The jester said in his heart: There is no God”). From a medieval point of view, this outrageous assertion that God did not exist was therefore decisive in making man a fool, as embodied in the figure of the jester. According to the view of the time, the “sapiens” (the wise man) was considered as such solely because he lived in the knowledge of God. Whoever lacked this knowledge of God was an “insipiens” (an unwise man) – a fool. St. Augustine had once written: “Timor Domini initium sapientiae” (“the fear of the Lord is the beginning of all wisdom”). As such, the origin of all foolishness was “contemptus Domini” (“contempt of the Lord”).

Psalter manuscript, 14th century, cover

The Fool’s Traits. Baldness and the Club

Since Psalm 52 was always illustrated in Psalter manuscripts with an initial that showed the “insipiens”, the fool, figuratively, the development of Psalter illustrations from the 13th to the late 15th century very neatly reveals the gradual external standardisation of the jester into a fixed type identified by very specific traits and attributes. In this early French psaltery from around 1250, the fool is depicted in the passage in question, “Dixit insipiens…”, as a lightly clad bald man carrying a type of club in his right hand and a loaf of bread with a sign of the cross in his left, which refers to a later text passage of the same psalm. For the non-specialist, this figure does not yet look exactly like a proper jester.

fool at the beginning of Psalm 52, Psalter with glosses by Petrus Comestor, France (Paris?) circa 1250, Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, B I 7, fol. 120

From Club to Sceptre

Half a century later, around 1300 and again in a French psaltery, the fool at the beginning of Psalm 52 has changed and an interesting refinement can be seen: While the baldness and the bread with the sign of the cross in one hand are still the same, the club now bears a little head on its upper end. The club has become the jester’s sceptre – what’s known as a “marotte”. This French word is related to “marionette”, and means something along the lines of “little doll”. In some languages, such as German and French itself, the word can also refer to a quirk or a fad, and those meanings can be traced back to the image of the medieval jester’s sceptre.

Fool with a marotte and bread, beginning of Psalm 52. Bible, France, circa 1300, The Hague, Rijksmuseum Meermanno-Westreenianum, 10 E 53, fol. 275 v.

Bells as Rollers

In this English Psalter, created another century later, the jester is fooling around in front of King David, trying to convince him that God does not exist by pointing a finger at his own mouth. The marotte here has regressed to a simple stick with a sagging pig bladder at the bottom. The “insipiens” now wears small bells on all the points of his garment and on the tip of his cap – in the form of the same “rollers” that many Fastnacht jesters still have today. They feature round metal hollow balls with a sound slot in which an object “rolls” back and forth, creating a sound.

Jester with bells in front of King David, beginning of Psalm 52, Princess Joan Psalter, England 1405, London, British Library, Royal MS 2, B.VIII fol. 54 v.

Donkey Ears and Rooster’s Head

By the end of the 15th century, the “insipiens” of Psalm 52 is fully developed, as this psaltery from 1490 shows. In the course of almost three centuries, he has developed from rudimentary beginnings into a firmly defined character whose appearance is distinctive thanks to very specific traits. Here, in a psaltery of the French King Charles VIII, he dances around in beaked shoes in front of the ruler David and can be identified by other features and attributes – above all, by the classic garment colours of yellow, red and blue as well as the donkey ears on his cap (as representation of foolishness). The cap is also topped by a rooster’s head covered with bells, which is repeated in miniature on the marotte – both indications of the fool’s unbridled sexual desire.

Jester with all attributes in front of King David, beginning of Psalm 52, Psalter of Charles VIII, France, circa 1490, Paris, Biliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Foolishness is Everywhere

In the 16th century, depictions of fools were omnipresent in the visual arts. They existed in book illustrations, in prints, on paintings and, last but not least, as sculptures in sacred as well as profane contexts. One example of hundreds is this carving by Albrecht Gelmers on the choir stalls of St. Catherine’s Church in Hoogstraaten, Flanders, dating from around 1540: A jester with a marotte and a donkey-eared cap looks at the viewer through his fingers. The gesture of seeing through one’s fingers meant as much as having a different view of things, or not being accurate with the truth. Jesters and fools, it was generally believed, were beings that existed outside of God’s order.

Fool with marotte looking through his fingers, carving on a choir stall by Albrecht Gelmers, circa 1540, Hoogstraaten, Sint-Catharinakerk, photo: Werner Mezger

Foolishness is Everywhere

In the 16th century, depictions of fools were omnipresent in the visual arts. They existed in book illustrations, in prints, on paintings and, last but not least, as sculptures in sacred as well as profane contexts. One example of hundreds is this carving by Albrecht Gelmers on the choir stalls of St. Catherine’s Church in Hoogstraaten, Flanders, dating from around 1540: A jester with a marotte and a donkey-eared cap looks at the viewer through his fingers. The gesture of seeing through one’s fingers meant as much as having a different view of things, or not being accurate with the truth. Jesters and fools, it was generally believed, were beings that existed outside of God’s order.

Fool with marotte looking through his fingers, carving on a choir stall by Albrecht Gelmers, circa 1540, Hoogstraaten, Sint-Catharinakerk, photo: Werner Mezger

Sebastian Brant and his Interpretation of the Times

The image of the jester largely owed its popularity at the time to the scholar Sebastian Brant, born in Strasbourg in 1457/58. After studying in Basel as a high-ranking jurist at the university there from the 1490s onwards, Brant became heavily involved in publishing that also extended far beyond the field of law. His most famous work, “Das Narrenschiff” (“Ship of Fools”), appeared in 1494. It clearly struck a chord and became the first bestseller alongside the Bible, thanks to numerous reprints and translations. In this rhymed moral satire, Brant – portrayed by Hans Burgkmair the Elder in the text – explained all the upheavals and strangeness of the world as manifestations of human foolishness. Within a few years, this made the figure of the foolish jester a ubiquitous symbol of the era.

Sebastian Brant, portrait by Hans Burgkmair the Elder, circa 1508, Basel, Öffentliche Kunsthalle

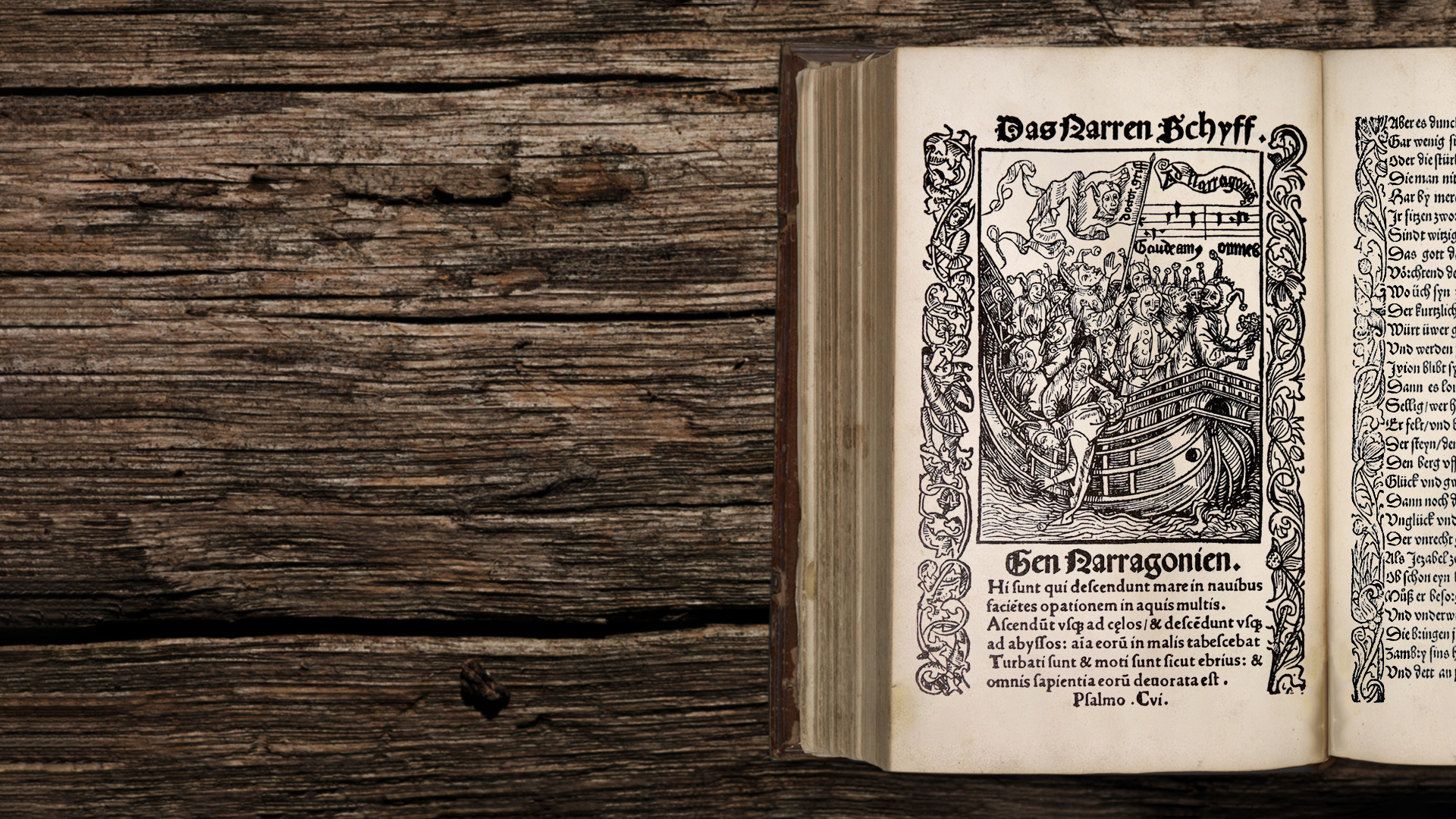

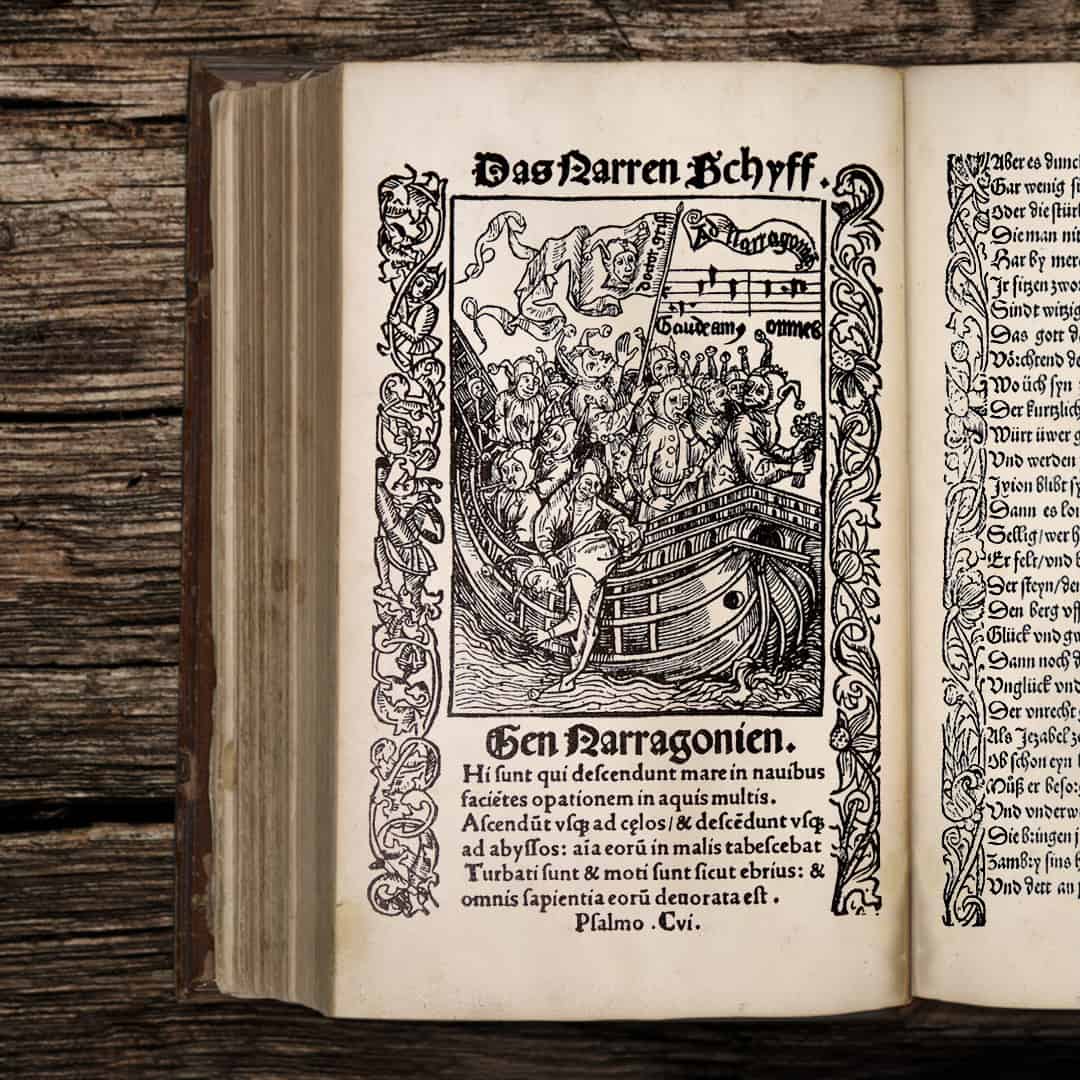

The Image of the Ship of Fools

The woodcut title of “Ship of Fools” depicts a group of densely packed fools with donkey ears, and some with marottes, drunkenly singing “Gaudeamus omnes” (“Let us all be merry”) as they drift towards their doom in a rudderless ship on the sea of the world. The transformation processes at the turn of the Middle Ages to the modern period were staggering: Social upheavals as precursors of the Peasants’ War, Church disputes that ultimately led to the Reformation, discoveries by seafarers that changed the image of the world as well as new scientific discoveries that the old ways of the Middle Ages could no longer withstand. All of this worried a lot of people. The fact that a contemporary critic like Sebastian Brant interpreted all of these upheavals as an epidemic of foolishness resonated well.

The Ship of Fools, woodcut of the back cover of Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Das Narrenschiff, Holzschnitt der Titelblattrückseite zu Sebastian Brant: Das Narrenschiff, Basel 1494

The Image of the Ship of Fools

The woodcut title of “Ship of Fools” depicts a group of densely packed fools with donkey ears, and some with marottes, drunkenly singing “Gaudeamus omnes” (“Let us all be merry”) as they drift towards their doom in a rudderless ship on the sea of the world. The transformation processes at the turn of the Middle Ages to the modern period were staggering: Social upheavals as precursors of the Peasants’ War, Church disputes that ultimately led to the Reformation, discoveries by seafarers that changed the image of the world as well as new scientific discoveries that the old ways of the Middle Ages could no longer withstand. All of this worried a lot of people. The fact that a contemporary critic like Sebastian Brant interpreted all of these upheavals as an epidemic of foolishness resonated well.

The Ship of Fools, woodcut of the back cover of Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Das Narrenschiff, Holzschnitt der Titelblattrückseite zu Sebastian Brant: Das Narrenschiff, Basel 1494

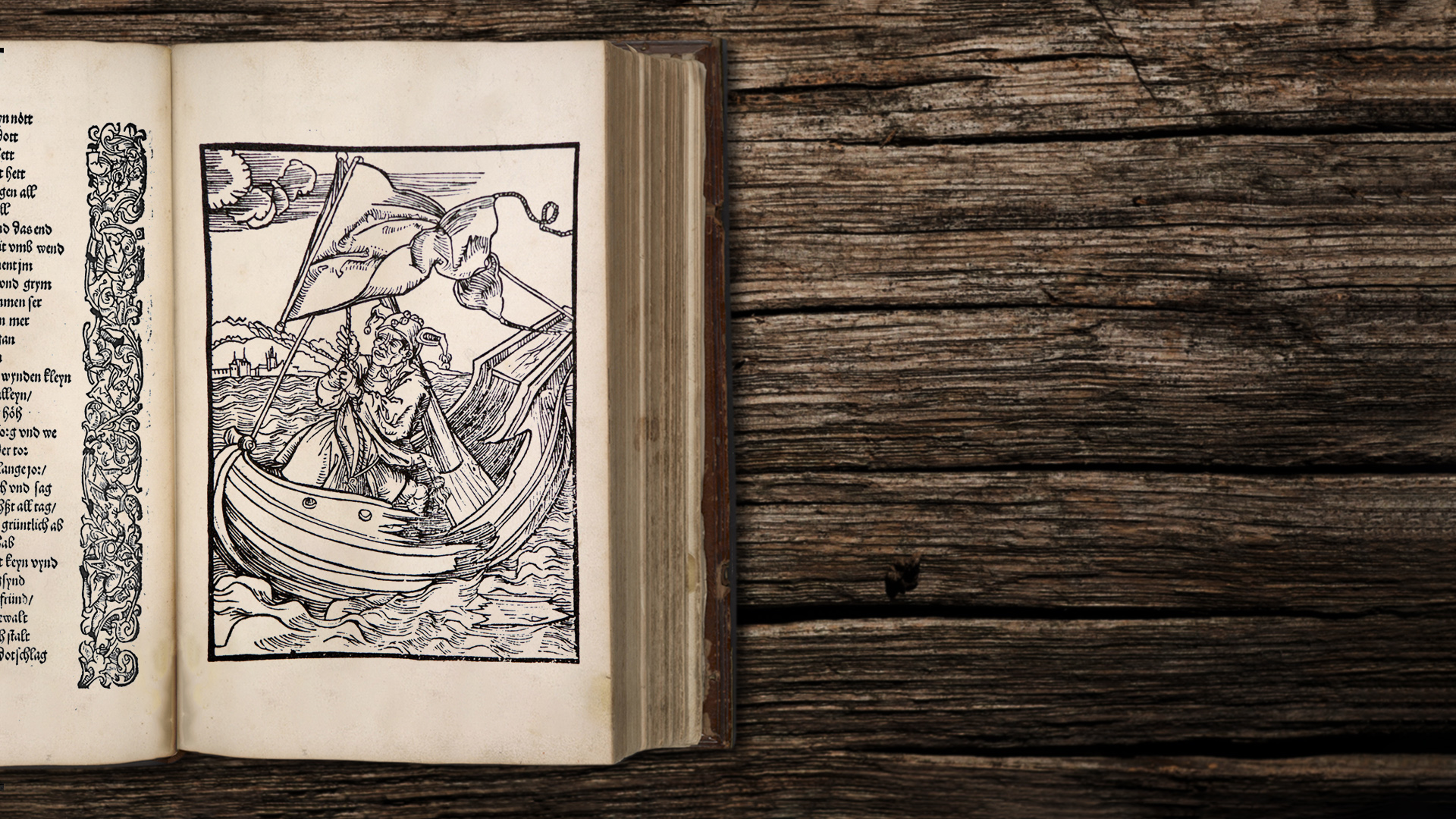

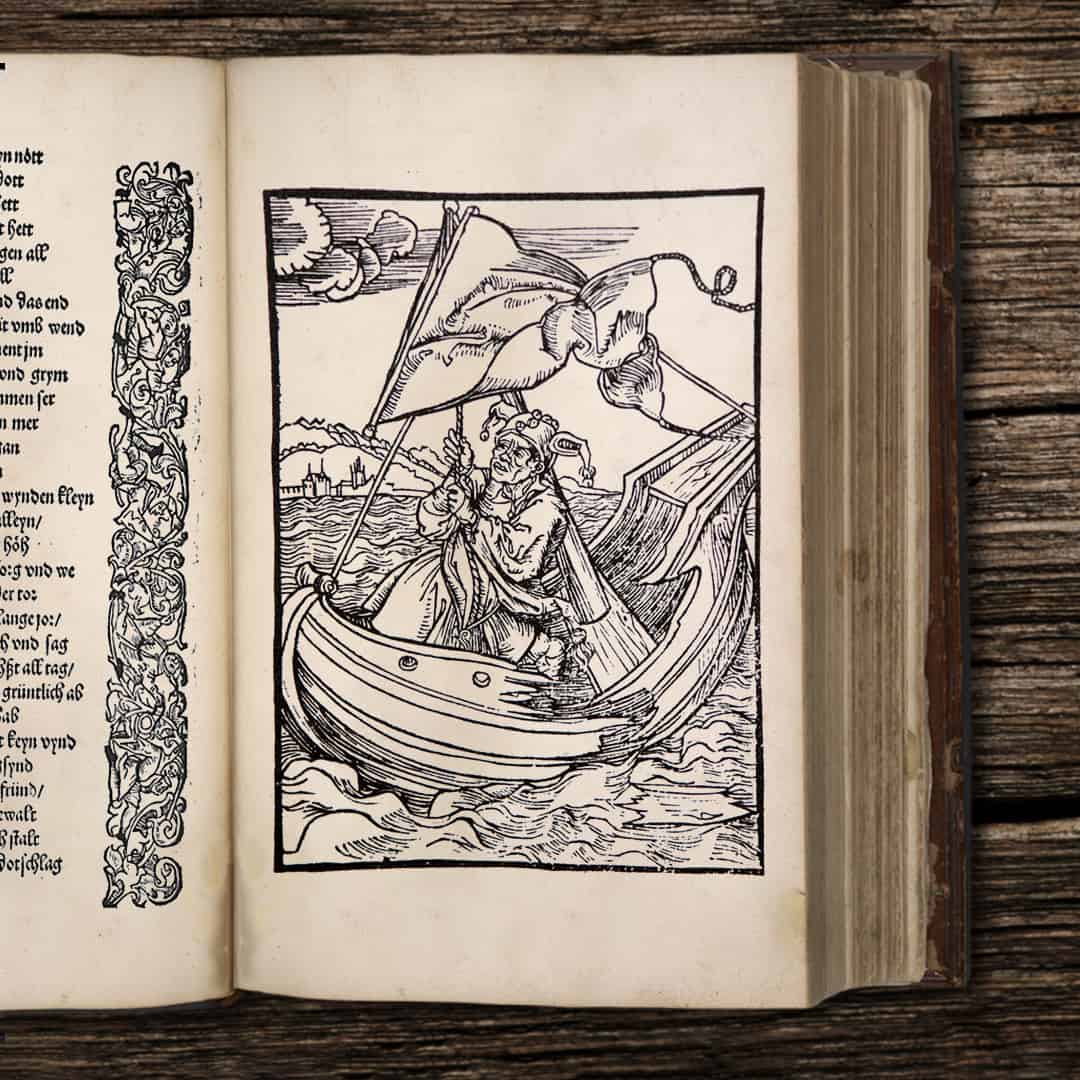

Shipwreck and Sinking

A woodcut (which, like most of the illustrations for “Ship of Fools” was done by Albrecht Dürer) shows with particular clarity how the jester is shipwrecked, and sinks. The epitome of human inadequacy and ignorance of God, he goes astray, wanders aimlessly, strikes his sails, is no longer able to keep his head above water and, ultimately, seals his own fate. The visual metaphor of the ship as humanity’s fate, which was very popular in the 1500s, is still present today. It was during these years in which Sebastian Brant’s book experienced enormous popularity, and in which the idea of the fool become widespread throughout Central Europe, that the jester also become more of a type of disguise for Fastnacht.

Shipwrecked fool, woodcut for Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Shipwreck and Sinking

A woodcut (which, like most of the illustrations for “Ship of Fools” was done by Albrecht Dürer) shows with particular clarity how the jester is shipwrecked, and sinks. The epitome of human inadequacy and ignorance of God, he goes astray, wanders aimlessly, strikes his sails, is no longer able to keep his head above water and, ultimately, seals his own fate. The visual metaphor of the ship as humanity’s fate, which was very popular in the 1500s, is still present today. It was during these years in which Sebastian Brant’s book experienced enormous popularity, and in which the idea of the fool become widespread throughout Central Europe, that the jester also become more of a type of disguise for Fastnacht.

Shipwrecked fool, woodcut for Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Ship of Fools versus the Nave of the Church

A particularly interesting woodcut from “Ship of Fools” is the one for the chapter titled “The Endkrist”. Here, the Antichrist squats on a capsized ship of fools and gets his evil ideas blown into his ears by the devil. Meanwhile, the fools sail up in small boats and try to catch the packed bag of money which the Antichrist lures them with, capsizing and sinking miserably. The story is quite different for those in the foreground sitting in “sant peters schifflin” (Peter’s little ship, or the ship of the church – the nave). They follow the example of Noah’s Ark, which saved the world, and are not seen wearing the jester’s cap. Instead, they are welcomed by Peter, with the key to heaven, upon the shore that has saved them. The transition from the ship of fools to the nave of the church was exactly what the church expected from the Fastnacht jesters on Ash Wednesday.

“The Endkrist”, woodcut for Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Ship of Fools versus the Nave of the Church

A particularly interesting woodcut from “Ship of Fools” is the one for the chapter titled “The Endkrist”. Here, the Antichrist squats on a capsized ship of fools and gets his evil ideas blown into his ears by the devil. Meanwhile, the fools sail up in small boats and try to catch the packed bag of money which the Antichrist lures them with, capsizing and sinking miserably. The story is quite different for those in the foreground sitting in “sant peters schifflin” (Peter’s little ship, or the ship of the church – the nave). They follow the example of Noah’s Ark, which saved the world, and are not seen wearing the jester’s cap. Instead, they are welcomed by Peter, with the key to heaven, upon the shore that has saved them. The transition from the ship of fools to the nave of the church was exactly what the church expected from the Fastnacht jesters on Ash Wednesday.

“The Endkrist”, woodcut for Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

The Foolish Ship during Fastnacht

In 1539, the main attraction of Nuremberg’s “Schembartlauf”, the most important city Fastnacht of the early modern era, was a huge ship of fools pulled through the streets on wheels blinded with ocean waves. On this ship, which was undoubtedly also inspired by Sebastian Brant, the repertoire of figures of the carnival of the time can be clearly seen: Jesters and devils mingle on deck and in the masthead, with the jesters outnumbering the devils. Incidentally, both mocked the Protestant theologian Andreas Osiander, depicted in a black costume with beret, which led to uproar and, ultimately, the banning of the “Schembartlauf” processions. The juxtaposition and coexistence of fools and devils was logical due to their proximity to each other over the course of history.

Fools and devils in a ship, “Hölle” of the Schembart run 1539, Schembart Book Nuremberg, circa 1590/1640, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Douce 346, 258 r.

The Fool on the Devil’s Reins

Another woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools” illustrates the affinity between the fool and the devil: It is the devil himself who leads the jester by the reins. The core statement “Non est Deus” (“There is no God”) characterised the fool since the early Psalter illustrations. He was the epitome of human aberration, inadequacy, sinfulness and contempt for God, and thus, at the same time, a symbol of doom and eternal damnation.

The fool on the short reins of the devil, woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

The Fool on the Devil’s Reins

Another woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools” illustrates the affinity between the fool and the devil: It is the devil himself who leads the jester by the reins. The core statement “Non est Deus” (“There is no God”) characterised the fool since the early Psalter illustrations. He was the epitome of human aberration, inadequacy, sinfulness and contempt for God, and thus, at the same time, a symbol of doom and eternal damnation.

The fool on the short reins of the devil, woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

Fool and Devil as One Person

A stone sculpture from 1609 on the Maison des Têtes, the House of Heads, in Colmar shows how closely related fools and devils were perceived even into the 17th century. On this building, richly decorated with figures, there is a window pillar showing a male hybrid with features of both the fool and the devil. The head is covered by a jester’s cap with donkey ears and bells and the upper part of the body is also dressed in a bell-covered garment. The lower part of the body, by contrast, ends in two legs with buck feet. There were, therefore, fluid transitions between the figures of devil and fool, which explains why the fool also established himself during Fastnacht as a logical complimentary figure to the devil.

Jester-devil hybrid, stone sculpture from 1609 at the Maison des Têtes in Colmar, photo: Werner Mezger

The Fool as a Despiser of God

The “Non es Deus”/”There is no God” sentiment as the quintessence of all foolishness was also something Sebastian Brant was still fully aware of when he wrote “Ship of Fools”, and was not softened by any trivialising additional aspects. As such, a woodcut in the book depicts a jester who, because of his contempt for God, even attacks the crucified Christ with a triple lance to further the torment the Saviour suffers to save humanity. According to the view of the time, fools were anything but funny beings or jokers. They were servants of the devil.

Fool attacking Christ on the cross, woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

The Fool as a Despiser of God

The “Non es Deus”/”There is no God” sentiment as the quintessence of all foolishness was also something Sebastian Brant was still fully aware of when he wrote “Ship of Fools”, and was not softened by any trivialising additional aspects. As such, a woodcut in the book depicts a jester who, because of his contempt for God, even attacks the crucified Christ with a triple lance to further the torment the Saviour suffers to save humanity. According to the view of the time, fools were anything but funny beings or jokers. They were servants of the devil.

Fool attacking Christ on the cross, woodcut from Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494

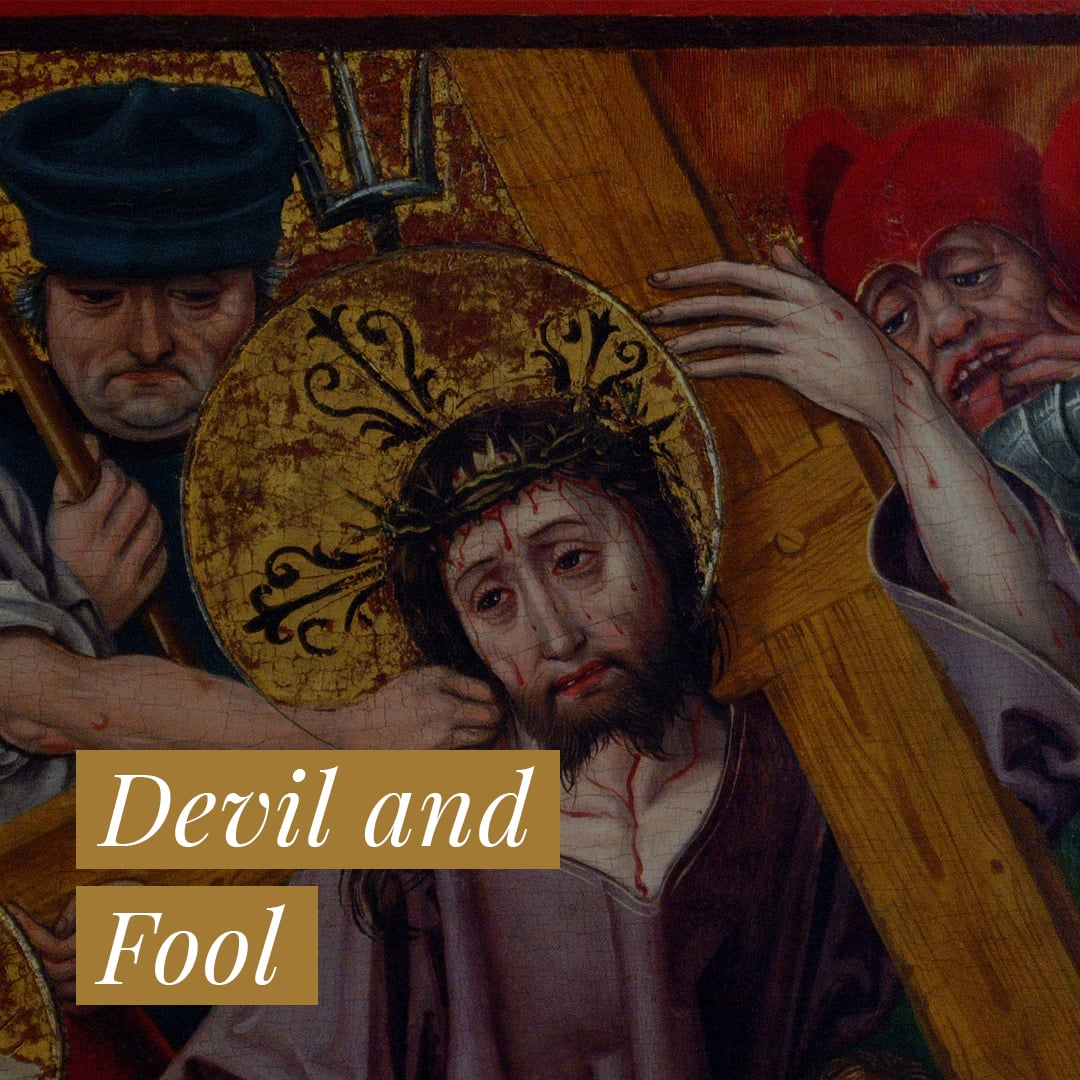

Fool’s Ridicule during the Bearing of the Cross

Against the backdrop of the jester figure’s contempt for God as his central trait, it is also not surprising that, on the cusp of the modern era, fools repeatedly appear in depictions of the Passion as Christ’s tormentors. One of many examples of this is a 15th century panel painting by a master painter from Baden in Switzerland, which can be seen in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Dijon, France. Here, the fool with a donkey-eared cap appears behind Christ carrying the cross, and mocks him by making a gesture in which he pulls apart the mouth with the fingers, causing his face to contort into a grimace. This gesture serves to vehemently deny the idea of the image of man as the image of God, which is emphasised in the story of creation.

Fool’s mocks Jesus Christ bearing the cross, panel by a master painter from Baden (Baden / Switzerland), 15th century, Dijon, Musée des Beaux Arts, photo: Werner Mezger

Fool’s Ridicule during the Bearing of the Cross

Against the backdrop of the jester figure’s contempt for God as his central trait, it is also not surprising that, on the cusp of the modern era, fools repeatedly appear in depictions of the Passion as Christ’s tormentors. One of many examples of this is a 15th century panel painting by a master painter from Baden in Switzerland, which can be seen in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Dijon, France. Here, the fool with a donkey-eared cap appears behind Christ carrying the cross, and mocks him by making a gesture in which he pulls apart the mouth with the fingers, causing his face to contort into a grimace. This gesture serves to vehemently deny the idea of the image of man as the image of God, which is emphasised in the story of creation.

Fool’s mocks Jesus Christ bearing the cross, panel by a master painter from Baden (Baden / Switzerland), 15th century, Dijon, Musée des Beaux Arts, photo: Werner Mezger

The Old Idea of Folly in Traditional Customs

Traces of the jesters’s denial of God have definitely survived in the traditional Fastnacht customs. An example of this is the appearance of the fool at the sword dance of the Rebleute (wine growers) in Überlingen, southwestern Germany – a guild dance that was originally part of Fastnacht, but is now performed in the summer following a vow procession. The story goes like this: The imperial city of Überlingen was once ordered by the emperor to provide 100 men for a war campaign. Before the march out, all of these men went to church – except for one, who had instead preferred to wander through the pubs. He did not survive the battle, while the others returned safely and were given the privilege by the emperor to perform a sword dance every year. It is said that, at the sword dance, the jester commemorates the one killed on the battlefield.

Sword dance in Überlingen, photo: Achim Mende, Überlingen, Marketing und Tourismus GmbH

The Old Idea of Folly in Traditional Customs

Traces of the jesters’s denial of God have definitely survived in the traditional Fastnacht customs. An example of this is the appearance of the fool at the sword dance of the Rebleute (wine growers) in Überlingen, southwestern Germany – a guild dance that was originally part of Fastnacht, but is now performed in the summer following a vow procession. The story goes like this: The imperial city of Überlingen was once ordered by the emperor to provide 100 men for a war campaign. Before the march out, all of these men went to church – except for one, who had instead preferred to wander through the pubs. He did not survive the battle, while the others returned safely and were given the privilege by the emperor to perform a sword dance every year. It is said that, at the sword dance, the jester commemorates the one killed on the battlefield.

Sword dance in Überlingen, photo: Achim Mende, Überlingen, Marketing und Tourismus GmbH

Fool’s Racket against the Church Bells

The traditional role of the “Hänsele” (the fool) during the sword dance is striking: Before the performance of their dance, the sword dancers take part in a festive church service together. The jester, however, is the only one not allowed to enter the church. Instead, he roams the pubs like his predecessor in the story. Only at the most important point of the mass, when the Hosanna bell of the Überlingen Cathedral rings for the consecration, does he appear in front of the church and disrupt this very solemn moment of the service by fighting against the ringing of the bells with cracking strokes of his “Karbatsche”, a short-handled whip. “Non est Deus”/”There is no God” was the defining statement of the earliest fools in the 13th century Psalter manuscripts. Through “Hänsele” and his actions at the Überlingen sword dance, more than seven hundred years of Western history of ideas have survived unchanged.

“Hänsele” with a “Karbatsche” in front of the Cathedral in Überlingen before the sword dance, photo: Helmut Reichelt