Origins and Development

Fastnacht – Germanic Heritage?

In older German folklore, the “mythologists” of the 19th century were fond of interpreting Fastnacht, with its use of disguises, as a “relic from Germanic prehistory” and an “ancient pagan winter expulsion ritual”. This interpretation reached a new peak during the Nazi era, given the Germanic motif supported the ideology of a Nordic culture. A training manual published in 1937 on behalf of the Reich Ministry of Propaganda on the “correct” celebration of the festivities, in line with the idea of the Nazi “racial community”, shows two Alemannic masks on the wheel of life as the title illustration. The word “Fasnacht” is clearly written without a “t” in order to blur its reference to the Christian Lent, and to establish a connection with the German word “faseln”, meaning “to be fruitful”. Modern research has disproved the Germanic and “winter expulsion” motif as an explanation, however it is still often repeated by amateur ethnologists and sometimes by the media, too.

Fools’ masks and the wheel of life, title illustration of the Nazi publication “Deutsche Fasnacht”, published by the Amt Feierabend (a sub-organisation of the Nazi organisation “Kraft durch Freude”), Berlin 1937

Roots in the Agricultural

Fastnacht, which is widespread far beyond the German-speaking world in many different European countries, cannot be explained in a monocausal way. It most definitely has several different origins. The oldest roots of the festival are probably rural rituals that celebrated the beginning of the new agricultural cycle after the winter vegetation break. The bells worn almost everywhere by the actors today, which originally came from cattle and pasture farming, possibly go back to this earliest level of the tradition.

Beyond the rural level, a reason for exuberant celebrations at the transition from winter to spring in the Mediterranean region certainly has its basis from the Roman calendar and its festivities around the turn of the year, which according to ancient Roman tradition was on 1 March.

“Mamuthones” in Mamoiada / Sardinia, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Roots in the Agricultural

Fastnacht, which is widespread far beyond the German-speaking world in many different European countries, cannot be explained in a monocausal way. It most definitely has several different origins. The oldest roots of the festival are probably rural rituals that celebrated the beginning of the new agricultural cycle after the winter vegetation break. The bells worn almost everywhere by the actors today, which originally came from cattle and pasture farming, possibly go back to this earliest level of the tradition.

Beyond the rural level, a reason for exuberant celebrations at the transition from winter to spring in the Mediterranean region certainly has its basis from the Roman calendar and its festivities around the turn of the year, which according to ancient Roman tradition was on 1 March.

“Mamuthones” in Mamoiada / Sardinia, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

From Ancient Festivals to the Christian Year

The extent to which specific Roman customs – such as the exchange of roles between slaves and masters during the Saturnalia, the lavish way of living during the Bacchanalia or even the masquerade of Roman theatre – had an impact on the form of what would become Fastnacht is questionable. It seems plausible, however, that the Roman festivities added an urban component to the agrarian celebrations that probably went back even further. However, Fastnacht only received its decisive form and its actual meaning much later – during the High Middle Ages via the Christian calendar, which gave it the role of a “threshold festival” before the Easter Lent. It was only then that the names “Fastnacht” (“the night before fasting”) or “Carnevale” (from “carnislevamen”, meaning “a break from meat”) came about, both referring to the approaching period of abstinence.

Two Roman theatre masks, mosaic from the Villa Adriana in Tivoli, 2nd century AD, Rome, Musei Capitolini

Farewell to Tasty Meat

As the last opportunity to eat and drink lavishly before the Easter fast, Fastnacht initially had a primarily economic function. Here, once again, all the foods not permitted during Lent were enjoyed – primarily meat, of course, but also milk, eggs, butter, cheese, lard and fat, which you also had to give up. In addition, people also drank a lot of wine again – while beer was allowed as a staple food during Lent. From the very beginning, the economic aspect of Fastnacht was, of course, accompanied by a social one. Eating lavish meals quickly developed into forms of socialising, from giving each other “carnival cakes” to community-building aspects such as music and dance – the basis for how Fastnacht would later be celebrated. Butchers’ rich supply of meat before Ash Wednesday, which was admittedly only available to a few, was strikingly depicted by painters such as Joachim Beuckelaer.

Butcher’s shop, painting by Joachim Beuckelaer, circa 1560, Naples, Museo Nazionale Capodimente

Fastnacht and Lent at Odds

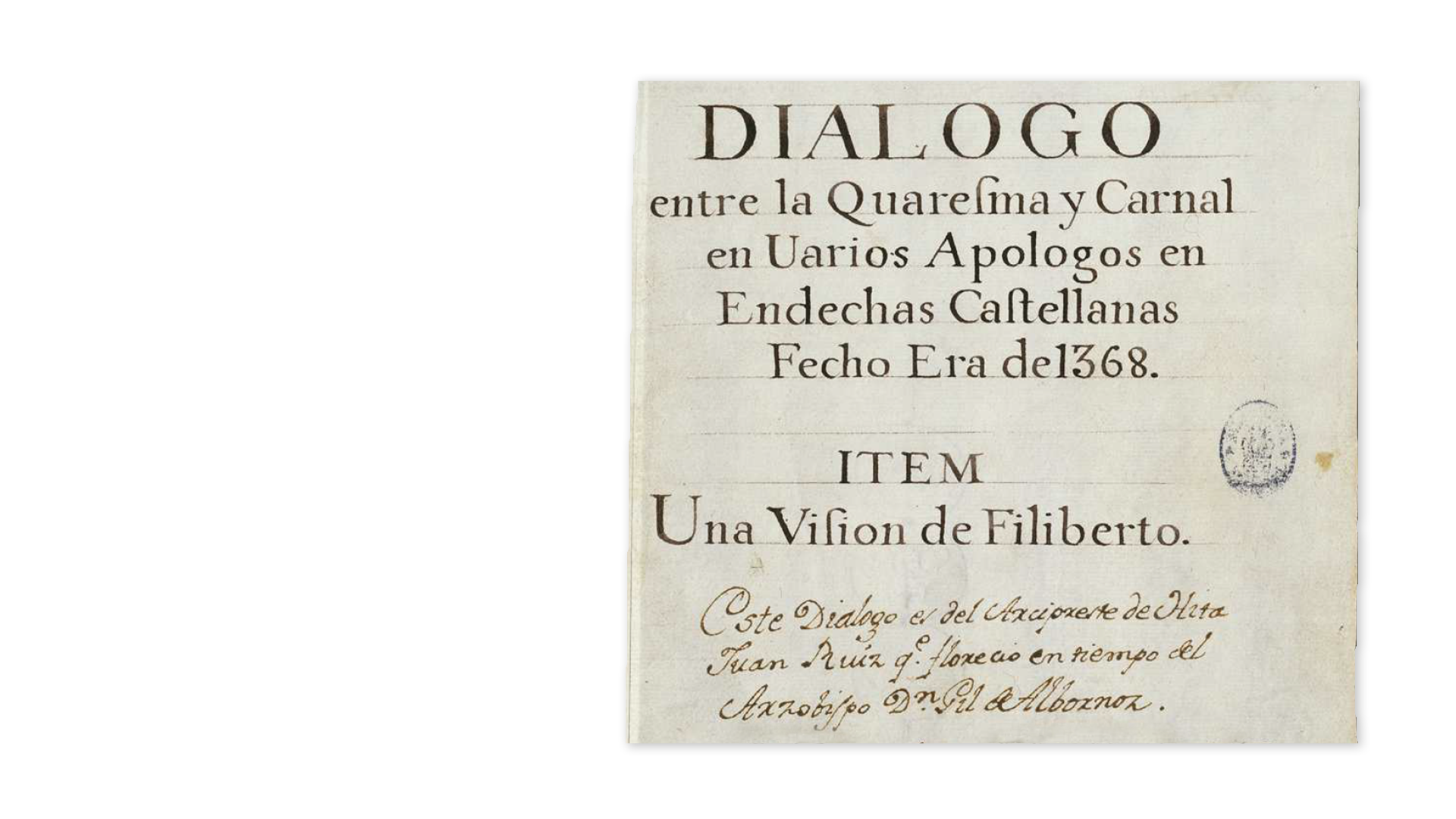

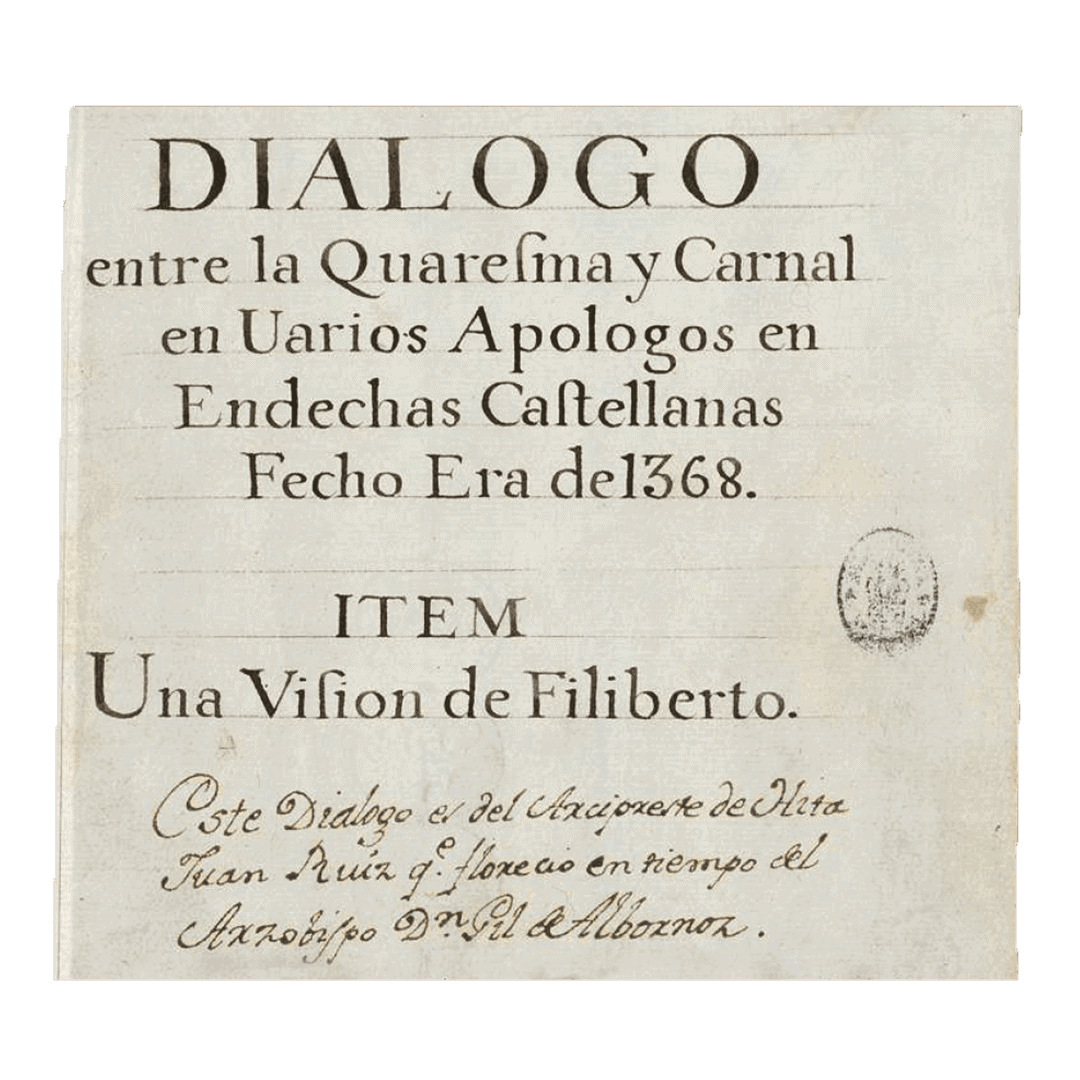

The contrast between the eating habits before and after Ash Wednesday soon found expression in literature in debates between Fastnacht and Lent. Among the earliest pieces of evidence of this are what are known as the “Contrasti” – controversial dialogues that, in the example of the Libro de Buen Amor by Juan Ruiz in Spain, go back to the first half of the 14th century and depict the conflict between Fastnacht and Lenten foods. While the older sources are only in writing, the theme later also became a popular motif in the visual arts.

Manuscript of the “Libro de Buen Amor” by Juan Ruiz, circa 1330/40, table of contents (subsequently added) with reference to the dialogue between Lent and Fastnacht, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional España

Battle of Two Times

In a 16th century Dutch painting in particular, a fixed visual type emerged in which the personifications of Fastnacht and Lent wage war against each other in a bizarre tournament. These representations could range from simple duels to entire battle scenes. Incidentally, the motif of the battle between two contrasting times fitted in well with the reality of Fastnacht, because in addition to food, drink, music and dance, it also featured actual tournaments as part of the festivities from an early stage.

Battle between Fastnacht and Lent, Pieter Bruegel Successor, 3rd quarter of the 16th century, Boston (Massachusetts), Museum of Fine Arts

The Theological Model of Interpretation

The more Fastnacht developed into a general folk festival, the more the Church became critical of it. Instead of seeing the difference between Fastnacht and Lent only in the contradiction between abundance and abstinence, the clergy increasingly elevated it to a theological-exegetical level. From the 15th century at the latest, Dominican and Franciscan monks in particular increasingly interpreted the two contrasting times of Lent and Fastnacht as a contrast between a blasphemous and a pious lifestyle, using St Augustine’s main work, “De citivate Dei” (“On the State of God”), as a basis for this. The woodcut title of an edition of this text printed in 1489 shows the Church Father Aurelius Augustinus at his writing desk in the upper section.

Saint Augustine at his writing desk, and below the two warring states of Jerusalem and Babylon, coloured woodcut from Aurelius Augustinus’ “De civitate Dei”, Basel 1489, Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, Aleph H III 32:1, p. 18

Augustine’s Two-State Doctrine

The lower section of the same woodcut visualises the core idea of the work, which is the struggle between the State of God and the State of the Devil. This is represented by the two opposing cities of Jerusalem (left) and Babylon (right), populated by angels in one and by devils in the other, and which are at odds with each other. In line with this Augustinian two-state model, preachers equated Lent with the State of God and Fastnacht with the State of the Devil by defining the days before Ash Wednesday as a sinful spectacle in which, in the truest sense of the word, the devil was once again loose – before the silent weeks of penance prior to Easter opened people’s eyes to God again.

The two warring states of Jerusalem and Babylon, lower part of a coloured woodcut from Aurelius Augustinus’ “De civitate Dei”, Basel 1489, Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, Aleph H III 32:1, p. 18

Demonisation of Fastnacht

The ecclesiastical interpretation of Fastnacht as an expression of the sinful world – its literal “demonisation” from the pulpits – also influenced the customs of festivities. Devils were the earliest masked figures to appear during Fastnacht. In Brunswick, where they ran around in hordes in the 15th century, they were called “Schodüfel”, meaning “show devils”. But they also dominated the scene in other cities – or, at the very least, played an important role. Their appearance was based on the depictions of devils in late medieval imagery. A pig-headed Fastnacht devil carrying the doll of a kidnapped infant, which cannot be dated precisely, has been preserved in several manuscripts from Nuremberg.

Fastnacht devil with pig’s head from a Schembart manuscript, Nuremberg, 16th century, Los Angeles UCLA, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Demonisation of Fastnacht

The ecclesiastical interpretation of Fastnacht as an expression of the sinful world – its literal “demonisation” from the pulpits – also influenced the customs of festivities. Devils were the earliest masked figures to appear during Fastnacht. In Brunswick, where they ran around in hordes in the 15th century, they were called “Schodüfel”, meaning “show devils”. But they also dominated the scene in other cities – or, at the very least, played an important role. Their appearance was based on the depictions of devils in late medieval imagery. A pig-headed Fastnacht devil carrying the doll of a kidnapped infant, which cannot be dated precisely, has been preserved in several manuscripts from Nuremberg.

Fastnacht devil with pig’s head from a Schembart manuscript, Nuremberg, 16th century, Los Angeles UCLA, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Invasion of the Fools

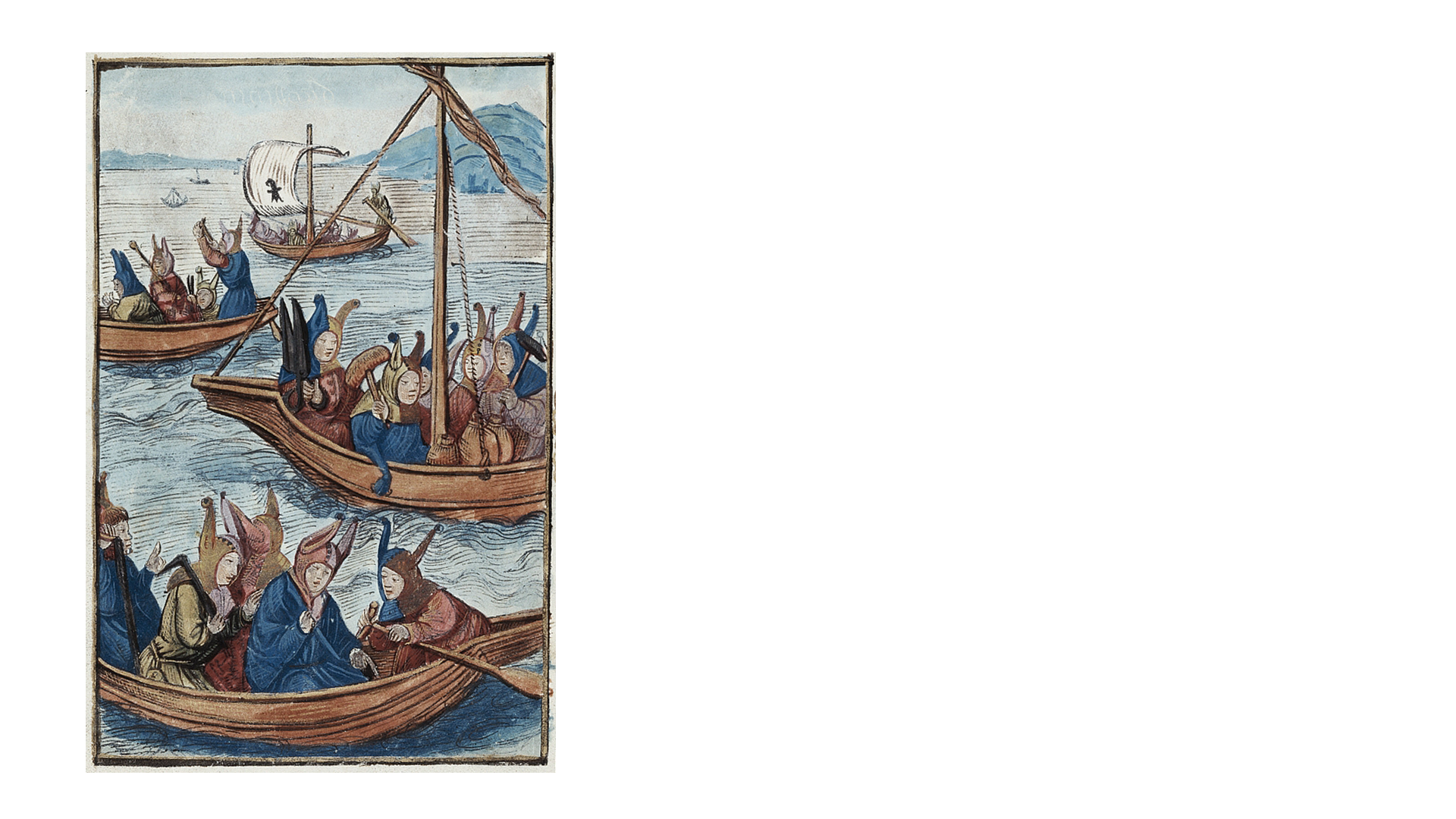

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, the devils began to find themselves in competition with other Fastnacht figures. The fools, above all, proved to be their biggest challengers. The fool became popular thanks to Sebastian Brant’s 1494 book “Das Narrenschiff” (“Ship of Fools”), which quickly became a bestseller. It explained all the folly of the world as the result of an epidemic of rampant foolishness. The fool thus became the symbol of an entire era, the symbol of man’s turning away from God and finally, during Fastnacht, an effective complementary figure to the devil. Sebastian Brant’s ship metaphor – conceived as a contrast to Noah’s Ark and its role in saving the good of the world – was particularly evocative. It showed that jesters and fools of all types bob along in small, rudderless boats on the sea of the world, drifting towards their doom.

Ship of Fools with craftsmen, coloured woodcut from a French edition of Sebastian Brant’s “Ship of Fools”, Basel 1494, Dresden copy

Martin Luther’s Perspective

As a result of the Reformation, Fastnacht experienced a significant turning point in the 16th century. Because Martin Luther abolished Lent as an act of penance decreed by the Roman Church and not justified by the Bible, Fastnacht’s purpose ceased to exist in the towns and areas that took on the new faith. Without pre-Easter abstinence, there was no longer any reason for one last bout of lavish eating, drinking and celebrating before Ash Wednesday. In addition, Luther categorically rejected the form of catechesis associated with Fastnacht by the monastic orders. Dabbling in the wicked world of the devil during Fastnacht, only to then return all the more consciously to a life committed to God upon entering Lent, contradicted his theological principles. As a result, Fastnacht became a custom that only made “sense” in areas which remained Catholic. In Protestant areas, it generally died out by itself.

Martin Luther, painting by Lucas Cranach

Sebastian Franck: Pagan Activity

The dynamics that Fastnacht developed in the Catholic world – as it disappeared in the Protestant one – can be learnt from the “Weltbuch” (“World Book”) by the Protestant scholar Sebastian Frank from 1534. He describes the Fastnacht of the Catholics as featuring women in “men’s clothes” and men in women’s clothes, fake monks, stilt walkers, wild people and animal figures such as monkeys, storks, bears and more. The image of Fastnacht, then, soon became very diverse in the places where it could still be found. As a Protestant, Franck repeatedly calls the activities of the Catholics “pagan” – “godless”. It was precisely this emotive word “pagan” – coming from the pens of Protestant critics of Fastnacht – that led older folklorists in the 19th century to misinterpret Fastnacht as a relic of Germanic prehistory. Instead of “pagan” as meaning “non-Christian” (that is, “Catholic”), which was actually what the Protestants intended, mythologists mistakenly understood the term “pagan” as meaning “pre-Christian” (that is, “Germanic”).

Sebastian Franck (1499 – 1542), posthumous copper engraving by Andreas Luppius, 17th century.

Italianisation of Fastnacht

During the 17th and 18th centuries, influences from Italy increasingly grew among the Fastnacht figures north of the Alps. Alongside the devils, wild people, animals and classic jesters (complete with donkey-eared cap, as they had become popular through Sebastian Brant), southern European characters including Bajazzo, Pulcinella, Domino and, last but not least, the harlequin, now joined in. A Dutch calendar painting for the month of February by Jan Caspar Philips from the mid-18th century shows a Shrove Tuesday scene. In it, the old-style donkey-eared jester (with sceptre) and the Italian harlequin (with chequered garment and slapstick) meet each other.

Jester and harlequin on Shrove Tuesday, picture of February, engraving by Jan Caspar Philips, Amsterdam mid-18th century, Amsterdam Rijksprentenkabinet, RP-P-1910-2725

Romantic Touch

The “Italianisation” of Fastnacht, which was also expressed in the increasingly frequent use of the Romance festival name “Carneval”, reached its peak in the German-speaking world in the 19th century. After the Enlightenment had declared war on the wild festivities before Ash Wednesday – which, by the end of the 18th century, had often degenerated into crude mischief – Fastnacht was later refined in many places in line with the spirit of Romanticism, and transformed into a bourgeois, civilised festival. The decisive impetus for this reform came from Cologne, where a completely new style of parade in 1823 marked the birth of the Rhineland Karneval. In the following decades, Cologne’s example also set a precedent in the German southwest. “Carneval” was also celebrated almost everywhere in this area, until in the south a gradual return to the earlier forms began shortly before 1900. Here, the Fastnacht of old – complete with its traditional masks – regained the upper hand.

Romanticising title illustration of the “Narrenbuch” from Tiengen am Hochrhein, started in 1843, Narrenzunft Tiengen Archive

Motivation of Modernity

Like the Rhineland Karneval, festivities in the Swabian-Alemannic region are no longer celebrated as a final, lavish “release” before Lent. Although the calendar linking Fastnacht to the Christian year still exists, Ash Wednesday no longer marks a turning point for most people. In an era of progressive secularisation, the religious context has receded into the background, and Fastnacht has also largely detached itself from any confessionalism. Today, there are other factors that make the festival attractive for actors and spectators: Celebrating together, escaping everyday life, playing with one’s own identity and role in society, experiencing interaction and togetherness, letting one’s emotions flow, cultivating tradition, celebration and much more. No other festival in recent times has experienced such an increase in clubs, guilds, actors and spectators as Fastnacht has.

#visitblackforest – Swabian-Alemannic Fasnet, video: Chris Keller / Schwarzwald Tourismus