Fastnacht and Karneval

Mockery of God and the World

In the time of Sebastian Brant, the fool was still considered an apocalyptic figure linked to the devil, and was therefore a frightening phenomenon. For example, a painting by the Dutch artist Cornelisz van Oostsanen from around 1500 shows the fool as an eccentric looking through his fingers with a twisted grin. A good generation later, however, the fool took on more and more humorous traits, and even acquired the attitude of a relaxed cheerfulness. In the visual tradition, the sarcastic laughter of these mockers of God and the world turned into a mischievous smile, and the early depictions of grimacing, sneering fools gave way to much friendlier portraits of smiling individuals with the ability to laugh at themselves.

Laughing Fool, painting by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen, circa 1500, Wellesley, David Museum at Wellesley College

Laughing at Oneself

Almost exactly a century after Sebastian Brant, between 1590 and 1600 Hendrik Gotzius also created an engraving in the Netherlands that explicitly addressed the fool’s laughter. He asked why and what the (now friendly) fool actually laughs – or should – laugh about. The caption (“Tis om te lachen”) sounds like an invitation to the viewer to take a closer look. With skilful strokes, a smugly smiling mischievous face looks out at us from the illustration, its amused facial expression with the shining, slightly narrowed eyes having an involuntarily infectious effect. This is no longer about derisive laughter at others – but rather serves as an invitation to laugh together and, undoubtedly, also to have the courage to be able to laugh at oneself. This is a fundamentally new conception of the nature of foolishness.

Laughing fool with marotte, engraving by Jan Saenredam from Hendrik Goltzius, Netherlands 1590/1600, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett RP-P-1882-A-6203

Humour as the Fool’s Gift

The key to understanding the picture is provided by the fool’s sceptre, his marotte – whose little head, with the pleated frilled collar, is the image of its bearer. The fool holds the miniature version of himself in his arms almost like a child, while the laughing marotte sticks out his tongue. And while the big fool laughingly points this out with his finger, the words in the caption become his own: “Tis om te lachen”. This shows the changed type of fool on the threshold of the Baroque era. He has gone from being ignorant of the divine order (as seen with Sebastian Brant) to being the bearer of a humorous worldview with which he encounters others and himself.

Laughing fool with marotte, engraving by Jan Saenredam from Hendrik Goltzius, Netherlands 1590/1600, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett RP-P-1882-A-6203, marotte details

Humour as the Fool’s Gift

The key to understanding the picture is provided by the fool’s sceptre, his marotte – whose little head, with the pleated frilled collar, is the image of its bearer. The fool holds the miniature version of himself in his arms almost like a child, while the laughing marotte sticks out his tongue. And while the big fool laughingly points this out with his finger, the words in the caption become his own: “Tis om te lachen”. This shows the changed type of fool on the threshold of the Baroque era. He has gone from being ignorant of the divine order (as seen with Sebastian Brant) to being the bearer of a humorous worldview with which he encounters others and himself.

Laughing fool with marotte, engraving by Jan Saenredam from Hendrik Goltzius, Netherlands 1590/1600, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett RP-P-1882-A-6203, marotte details

Happy Fastnacht Fools

The new, friendly and humorous image of the fools also had an impact on the way Fastnacht, of which the fool was still the central figure, was celebrated. From the turn of the 16th to the 17th century at the latest, the traditional public rituals such as tournaments, masked parades or guild dances were increasingly supplemented by spontaneous forms of sociability and happiness, which were aimed simply to create fun and laughter.

Augsburg Fastnacht tournament with fools circa 1480, from: Marx Walther: “Turnierbuch und Familienchronik”, Augsburg 1506 – 1511, Munic, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Cgm 1930

Fools during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities in Fridingen an der Donau, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Hidden in the Southwest

During today’s Fastnacht customs in German-speaking countries, uninhibited joie de vivre, spontaneity and laughter are spread very differently from region to region. The Swabian-Alemannic Fasnet In particular creates a rather restrained impression – due to participants being fully masked during the street processions – and is far from being a hotbed of excessive happiness. The faces of the fools, hidden behind wooden face masks, puzzles the spectators and may even seem slightly strange to first-time visitors. Instead of the pull of jubilation and hustle and bustle, it is more the fascination of being different, as well as the dignity of a long-established tradition, that make the festivities so attractive. It is only when the masked fools come into contact with unmasked participants and spectators, and all kinds of unsettling conversations develop between people who do and do not know each other, that the humour and the funny side of this kind of Fastnacht come to the fore.

Fools during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities in Fridingen an der Donau, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Hidden in the Southwest

During today’s Fastnacht customs in German-speaking countries, uninhibited joie de vivre, spontaneity and laughter are spread very differently from region to region. The Swabian-Alemannic Fasnet In particular creates a rather restrained impression – due to participants being fully masked during the street processions – and is far from being a hotbed of excessive happiness. The faces of the fools, hidden behind wooden face masks, puzzles the spectators and may even seem slightly strange to first-time visitors. Instead of the pull of jubilation and hustle and bustle, it is more the fascination of being different, as well as the dignity of a long-established tradition, that make the festivities so attractive. It is only when the masked fools come into contact with unmasked participants and spectators, and all kinds of unsettling conversations develop between people who do and do not know each other, that the humour and the funny side of this kind of Fastnacht come to the fore.

Fools during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities in Fridingen an der Donau, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Exposed in the Rhineland

The Rhenish Karneval is very different from the masqueraded Alemannic festivities. There is more spontaneous happiness seen during Karneval – mainly because participants are not fully masked, but perhaps also due to a difference in mentality. People approach each other more openly, the distance between participants and spectators (who are also in costume) is smaller, emotions are allowed, and people can laugh, cry and kiss. Not to mention the tonnes of sweets that rain down from the floats onto the people along the roadside during the Rose Monday processions. The exuberance of the Rhenish celebrations was often criticised by traditionalists of the south, especially in the 20th century. In a paradoxical superiority-inferiority complex, even folklorists asserted that, in contrast to the “traditional” Alemannic Fastnacht, the Rhenish Karneval was superficial, lacked tradition, and was simply a shallow big city entertainment event. With all of that in mind, the following overview looks at how Fastnacht and Karneval actually relate to each other, and how both have developed.

“Jecken” during Rhenish Karneval festivities, photo: Festkomitee Kölner Karneval 1823 e. V., courtesy of the Festkomitee

Exposed in the Rhineland

The Rhenish Karneval is very different from the masqueraded Alemannic festivities. There is more spontaneous happiness seen during Karneval – mainly because participants are not fully masked, but perhaps also due to a difference in mentality. People approach each other more openly, the distance between participants and spectators (who are also in costume) is smaller, emotions are allowed, and people can laugh, cry and kiss. Not to mention the tonnes of sweets that rain down from the floats onto the people along the roadside during the Rose Monday processions. The exuberance of the Rhenish celebrations was often criticised by traditionalists of the south, especially in the 20th century. In a paradoxical superiority-inferiority complex, even folklorists asserted that, in contrast to the “traditional” Alemannic Fastnacht, the Rhenish Karneval was superficial, lacked tradition, and was simply a shallow big city entertainment event. With all of that in mind, the following overview looks at how Fastnacht and Karneval actually relate to each other, and how both have developed.

“Jecken” during Rhenish Karneval festivities, photo: Festkomitee Kölner Karneval 1823 e. V., courtesy of the Festkomitee

Unrecognisability as an Old Game

For centuries, the forms of Fastnacht were very similar from the Netherlands to the edge of the Alps. Apart from the maskless fool with the donkey-eared garment, the principle of being fully masked and unrecognisable applied to the majority of participants, as is now only customary in southern Germany. A copper engraving from the 1580s made in Antwerp, which depicts February in a series of monthly pictures, shows a group of masks with a hidden identity during a visit to a distinguished couple. Very similar “Vastenavond” face masks can also be found a few decades earlier in pictures by the Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel.

Masked Fastnacht figures in the late 16th century, picture of February (detail), engraving by Crispijn van de Passe after Marten de Vos, Antwerp 1580/90, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, RP-P-OB 15.842

Before 1800: Masks in the North and South

The only known image of Fastelovend festivities in Cologne before 1800 confirms that face masks were also common on the Lower Rhine. The aforementioned depiction from the family book of the Cologne citizen Moses Valens from the beginning of the 17th century shows the appearance of four noble masked figures among distinguished people in a Cologne patrician house. Reports (though not pictures) testify that being fully masked also shaped the Cologne street Fastnacht. It was mainly groups of young craftsmen, called “Banden” (“gangs”) in Cologne, who carried out “Mommen” in public – that is, who wandered around in disguise and performed all sorts of jokes and mischief. A certain difference between the Rhenish and the southern German disguises seems to have existed only in the fact that many masquerade costumes in the south had been hung with large bell straps since the 18th century at the latest, which was apparently less familiar in the Low German region.

Masked attendees at a Cologne masquerade ball, illustration from the family album of Moses Valens, between 1606 and 1616, London, British Library, Ms. Add. 18991 fol. 11

Before 1800: Masks in the North and South

The only known image of Fastelovend festivities in Cologne before 1800 confirms that face masks were also common on the Lower Rhine. The aforementioned depiction from the family book of the Cologne citizen Moses Valens from the beginning of the 17th century shows the appearance of four noble masked figures among distinguished people in a Cologne patrician house. Reports (though not pictures) testify that being fully masked also shaped the Cologne street Fastnacht. It was mainly groups of young craftsmen, called “Banden” (“gangs”) in Cologne, who carried out “Mommen” in public – that is, who wandered around in disguise and performed all sorts of jokes and mischief. A certain difference between the Rhenish and the southern German disguises seems to have existed only in the fact that many masquerade costumes in the south had been hung with large bell straps since the 18th century at the latest, which was apparently less familiar in the Low German region.

Masked attendees at a Cologne masquerade ball, illustration from the family album of Moses Valens, between 1606 and 1616, London, British Library, Ms. Add. 18991 fol. 11

Napoleon the Killjoy

Both in the Rhineland and in southern Germany, the Fastnacht revelry of masked craftsmen on the streets fell increasingly into disrepute towards the end of the 18th century. Representatives of the Enlightenment, in particular, took a stand against these festivities because they were “not worthy of decent citizens”. The big break, however, came in the wake of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s intervention in European history. Cologne was occupied by French troops as early as 1794. With the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Napoleonic France gained the upper hand over the area on the right bank of the Rhine with the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine. There were also far-reaching territorial changes under Napoleon in southwestern Germany. Wuerttemberg and Baden became territorial states practically over night, with powerful rulers strengthened by Napoleon’s grace. Of course, all of these upheavals were not without consequences for the popular culture of the new areas of rule, and not least for Fastnacht.

Napoleon Bonaparte Crossing the Alps at the Great Saint Bernard, painting by Jacques-Louis David, 1800, Rueil-Malmaison, Musée nationale du Château de Malmaison

Karneval Ban in Cologne

The first Fastelovend in Cologne after the occupation of the city by the French on 6 October 1794 quickly came under massive pressure due to the restrictions of the new regime: On 12 February 1795, the French city commander Daurier issued a strict ban on any mask wearing in streets and alleys. This affected the young wandering craftsmen in particular, whose traditional “Mommen” out in the open came to an abrupt end. For wealthy Cologne residents, on the other hand, there were soon exemptions to hold masked balls in halls. Ball events were allowed to take place in closed rooms subject to conditions and upon payment of a high “mask tax” – the proceeds of which, by order of the occupiers, went to relief for the poor. Mask-wearing was therefore reduced to the elegant social events of the upper middle classes, while the wearing of masks by the common people as well as the humble street Karneval itself practically disappeared.

Ban on all Karneval events in Cologne by the French city commander Daurier on 12 February 1795

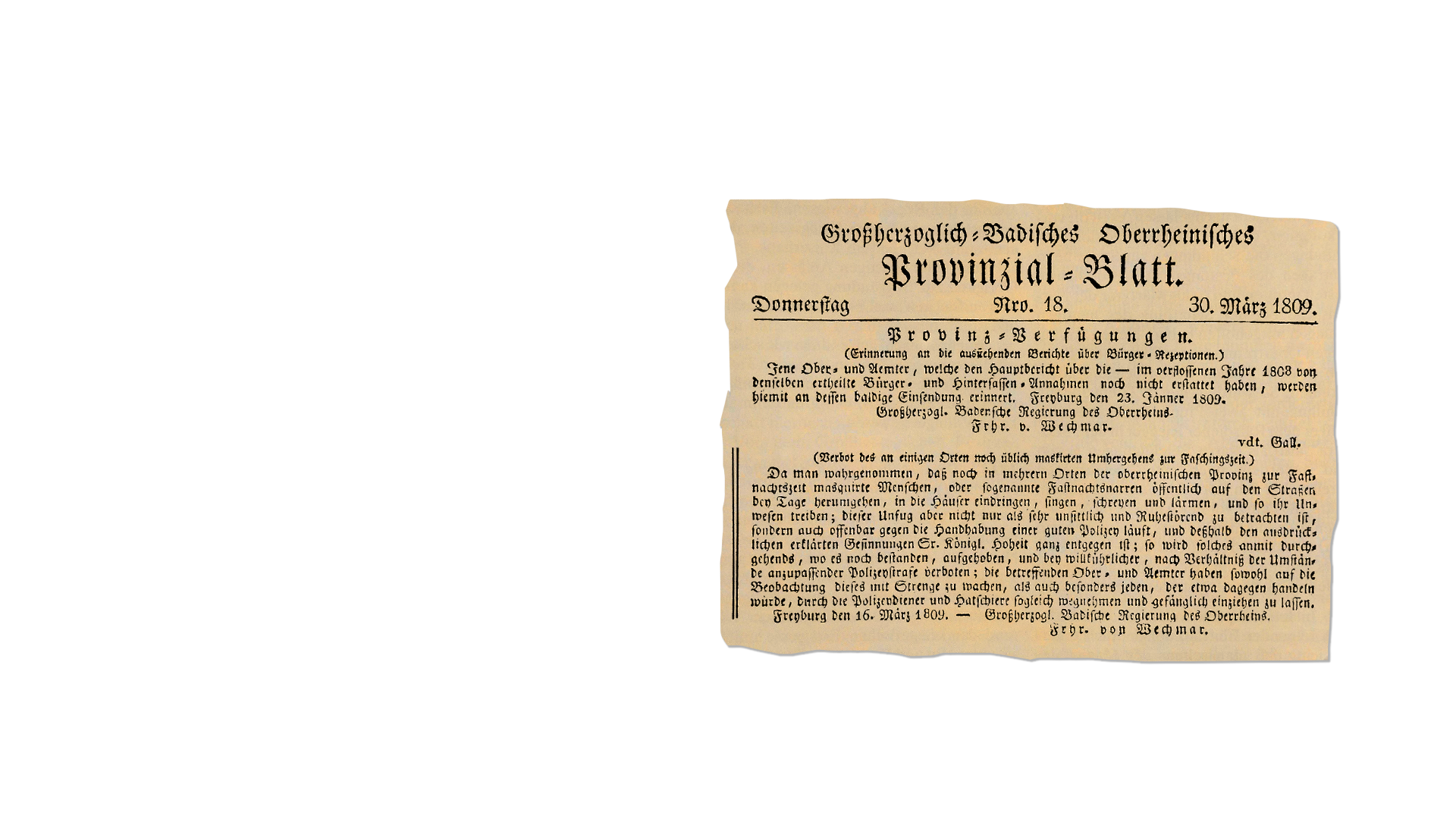

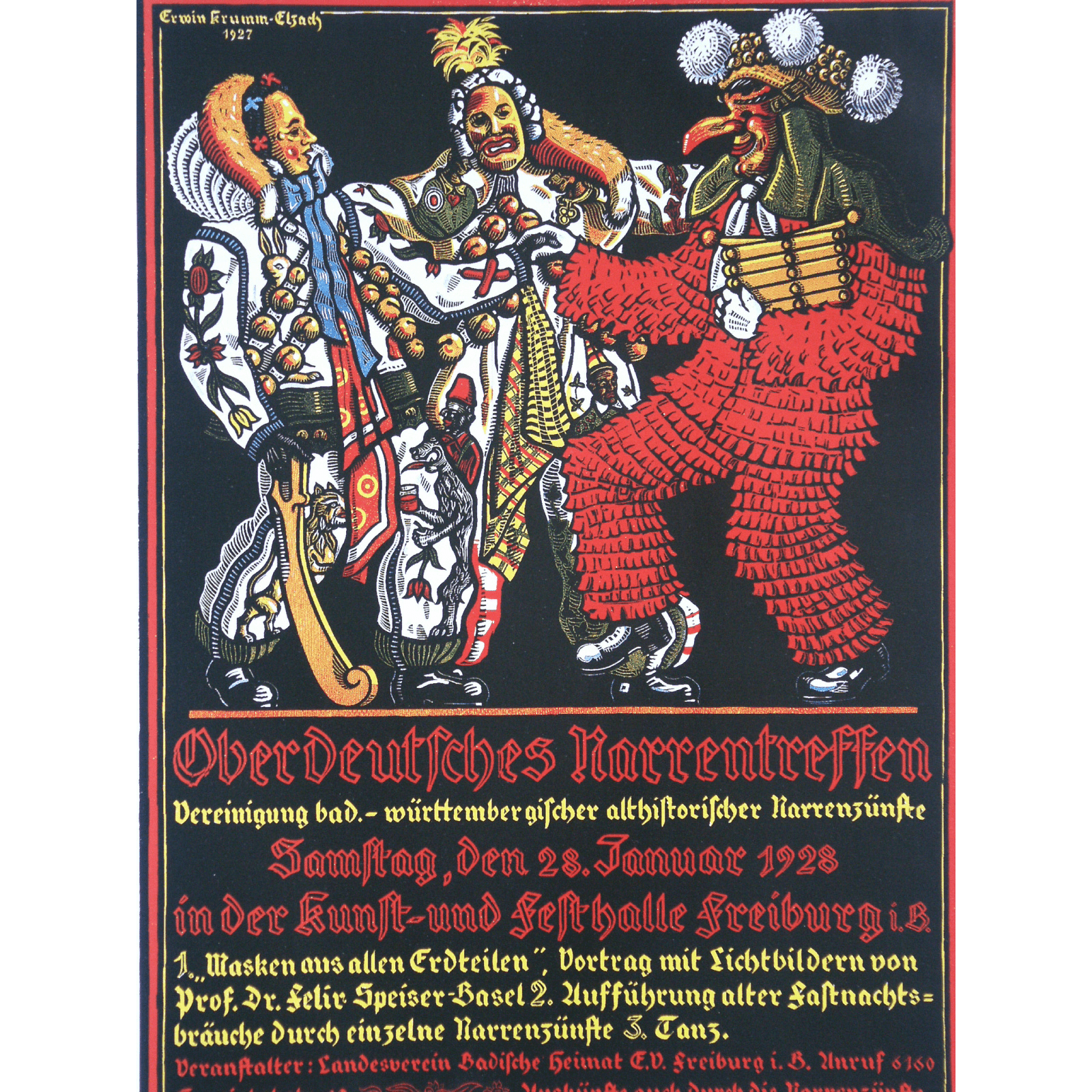

Fastnacht Ban in Baden

There was a very similar development in southwestern Germany, where the street Fastnacht was also largely in the hands of young wandering craftsmen until the end of the 18th century. The reputation of Fastnacht declined rapidly after Enlightenment thinkers, encouraged by the reforms of Emperor Joseph II, had already voiced criticism of the “outdated spectacle of foolishness” in the pre-Napoleonic period. The line was finally drawn in January 1809 by the government of Wuerttemberg, which had been elevated to a kingdom by Napoleon three years earlier. The government of Baden, which had become a Grand Duchy, followed a few weeks later. Both administrations issued an indefinite general ban on all forms of street Fastnacht, which effectively meant the end of all Fastnacht traditions.

General ban on all Fastnacht events by the Grand Ducal Baden Government of the Upper Rhine on 16 March 1809

Old Fastnacht face mask (“Harzer”) from Schömberg, late 18th century, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Rescued Fastnacht Treasures

Since the Fastnacht strongholds in southwestern Germany were often reluctant to comply with their new sovereigns, there were repeated violations of the bans in the years that followed. But this did nothing to change the fact that traditional Fastnacht culture was suffering. The population feared sanctions after every case of insubordination. In many places, old masks were hidden in remote parts of houses because there were concerns that they might be confiscated by the police. This is what happened to this Schömberg face mask (the “Old Harzer”) from the late 18th century. It only reappeared years after its disappearance behind the chimney of a farmhouse, and today is one of the oldest surviving pieces of evidence of the Schömberg Fasnet.

Old Fastnacht face mask (“Harzer”) from Schömberg, late 18th century, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Rescued Fastnacht Treasures

Since the Fastnacht strongholds in southwestern Germany were often reluctant to comply with their new sovereigns, there were repeated violations of the bans in the years that followed. But this did nothing to change the fact that traditional Fastnacht culture was suffering. The population feared sanctions after every case of insubordination. In many places, old masks were hidden in remote parts of houses because there were concerns that they might be confiscated by the police. This is what happened to this Schömberg face mask (the “Old Harzer”) from the late 18th century. It only reappeared years after its disappearance behind the chimney of a farmhouse, and today is one of the oldest surviving pieces of evidence of the Schömberg Fasnet.

Old Fastnacht face mask (“Harzer”) from Schömberg, late 18th century, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

New Beginnings and Cologne Refinement

In that difficult first quarter of the 19th century, when the continued existence of Fastnacht throughout the German-speaking world was on the line, a decisive impetus to save the old traditions with contemporary changes came from Cologne. In 1823, seven years after the French had withdrawn and with the Prussians as the new rulers of the city, some notable Cologne citizens got together and developed a refined design for the festivities along romantic lines. Within a few weeks, they organised a completely new style of procession with an educated bourgeois aesthetic for Shrove Monday of that year. Although it was short, it was a resounding success as a new beginning that continued Karneval’s history. The organising committee, whose members are all still known by name, called itself the “Festordnendes Komitee” a year later and was the origin of today’s Cologne Karneval Festival Committee.

“Festordnendes Komitee” in Cologne 1823, coloured drawing, Cologne, Farina Archiv

Birth of the Rhenish Karneval

As it turned out, the year 1823 was decisive for the survival of Fastnacht in the entire German-speaking area, and it also marked the birth of the “Rhenish Karneval”. The focus of the first Cologne procession was the entry of “King Carneval” into the city and his marriage to Princess Venetia. This combination of figures essentially officially united the “Nordic” Fastelovend with the southern European-Italian tradition, in the same way the Italian name “Carneval” was now used more often than the old name “Fastelovend”. No pictures of the premiere in 1823 have survived, but there is visual evidence of the procession of the following year, where the two central figures were again present. The image shows the male protagonist in a dolphin-shaped boat. From the second year of his appearance onwards, and on Prussian orders, he was now called “Hero Carneval” instead of “King Carneval”. Dynastic names that would have disparaged the Prussian king were not approved of.

“Hero Carneval” in on a dolphin-shaped boat in 1824, coloured engraving, Cologne, Stadtmuseum

Imperial City Nostalgia

In the Cologne mask procession of 1825, which has been preserved in visual detail, one military group stands out. They are the “Kölschen Funken rot-weiß”, extras dressed as the old Cologne city soldiers from the time before 1794. They had already been applauded at the 1823 premiere as a reminder of the city’s imperial past. They have featured in every procession from the very beginning, and are still part of the core of the Cologne Karneval today. The fact that the Prussians allowed their appearance at all, despite the strict ban on non-official uniforms, was based on an ulterior decision: The occupiers did not regard the old Cologne soldier’s frocks in the imperial city colours of red and white as uniforms at all, but simply as costumes. In this way, they essentially declared the former municipal military to be an operetta troupe. In response, the “Funken” (Cologne “soldiers”) acknowledged this Prussian attitude in a backhanded way with dummy rifles with bouquets of flowers in the barrels, as well as with comical drill rituals such as the “Stippeföttche”. So, both sides ironised each other. For the people of Cologne themselves, however, their “Funken rut-wieß” were far less a parody than an element of nostalgia.

Cologne mask procession on Rose Monday 1825, coloured engraving by Jodocus Schlappal, Cologne, Stadtmuseum, graphic arts collection

From the Lower Rhine to the Middle Rhine

The new form of the Cologne Karneval defined a style for the entire Rhineland, and far beyond. Numerous cities followed the example of Cologne: Koblenz in 1824, Düsseldorf in 1825, Bonn in 1826, Düren in 1827, Aachen in 1829, and Bingen in 1833. Mainz was the last major location to adopt the example set by Cologne. There, “Hero Carneval” first made an appearance in 1838. With the expansion of the Lower Rhine Karneval concept to the Middle Rhine, another stronghold emerged in Mainz which made a name for itself throughout Germany, especially in the 20th century. From the 1950s onwards, Mainz established itself in the new medium of television with the “Saalkarneval” – an event that also flourished in the other metropolises, but which was widely popular nationally thanks to its strongly literary-word-based form, and the relatively easy-to-understand Mainz dialect. The annual television broadcast of the ceremonial meeting from the electoral palace under the title “Mainz as it sings and laughs” became a cult TV programme for the young Federal Republic.

Call for the first Karneval procession in Mainz 1838, newspaper advertisement

‘Karnevalisation’ of the South

The Rhenish Karneval also had an impact in southern Germany from the middle of the 19th century at the latest. The old mask-wearing of the young wandering craftsmen, which had actually been forbidden since 1809, was, where it still survived, only a stumbling block for the authorities and the educated bourgeoisie. The “upper circles” met during Fastnacht for dances, balls and redoubts that the common people could not afford. In Rottweil, for example, the Hotel Gassner invited guests to a dance in 1857 for 24 kreuzers, at which Wuerttemberg military musicians from the 4th Rider Regiment from Ludwigsburg played. And at the time, Fastnacht was known as “Carneval” in Rottweil.

Carneval in Rottweil, ball advertisement from 1857 in the Gemeinnütziger Anzeiger

The Upper Circles get Organising

In Donaueschingen in 1864, “Prince Carneval” also arrived following the Rhenish model (instead of the earlier fools featuring wooden face masks and bells), to whose “dignified reception” the fool’s committee “most humbly” invited. This is what the advertisement in the local proclamation paper declared. This was no longer the language of humble craftsmen, but rather the diction of the upper middle classes. But it was precisely this social paternalism that the original bearers of the old Fasnet began to dislike after only a few years, because they did not see themselves in what was now being organised. For the common people, elegant balls and redoubts were not part of their world anyway. The middle-class refinement of “Carneval” had ensured the survival of Fastnacht and made it more or less respectable, but little by little the common people decided to return to its older forms.

Carneval in Donaueschingen, advertisement from 1864, Verkündungsblatt

Countermovement from Below

In some places in the southwest, the craftsmen’s turning away from the new form of Carneval was already noticeable around the time of the Franco-Prussian War. Given there was still no final peace treaty by Fastnacht in 1871, all festivities were suspended because of the seriousness of the situation at the time. In Rottweil, the owners of historic masquerade costumes posed for at least one photo in 1871, which became the earliest group photo of the traditional Rottweil Fasnet. This photo only shows the face masks and garments worn by the city’s young journeymen of the Baroque era – there is not a trace of the fashionable Karneval of the better-off. Although the bourgeois-themed processions later continued to exist parallel to the traditional Fastnacht for a while, they were eventually pushed aside. With the resurgence of the traditional form, the Karneval interlude in the south came to an end.

Earliest photograph of a large group of Rottweil fools 1871, “Narrentafel”, Rottweil, Stadtmuseum

Rhineland: Holding on to the New

In Cologne, as in the entire Rhineland, there was no such return to the mask-wearing of the time before 1800. Rapid population growth in the Rhenish metropolises probably meant that, unlike in the provincial fool towns of the southwest, the former mask-wearing “Mommen” groups no longer existed. As a result, the new form of Karneval was able to cement itself. Since then, there have been two types of celebration in Germany: The Rhenish Karneval with its cheerful spontaneity on the one hand, and, on the other, the somewhat more reserved southern German Fastnacht. However, the two are not opposites – they are simply two branches of the same fool’s tree. The most important Karneval symbol in Cologne since 1870 has been the “Dreigestirn” (triumvirate) consisting of the figures of the prince, peasant and maiden. Here is the Cologne “Trifolium” from 1907.

Cologne triumvirate from 1907, prince, peasant and maiden (from left to right), photo: Köln, Karnevalsmuseum

Southwest: Return to the Old

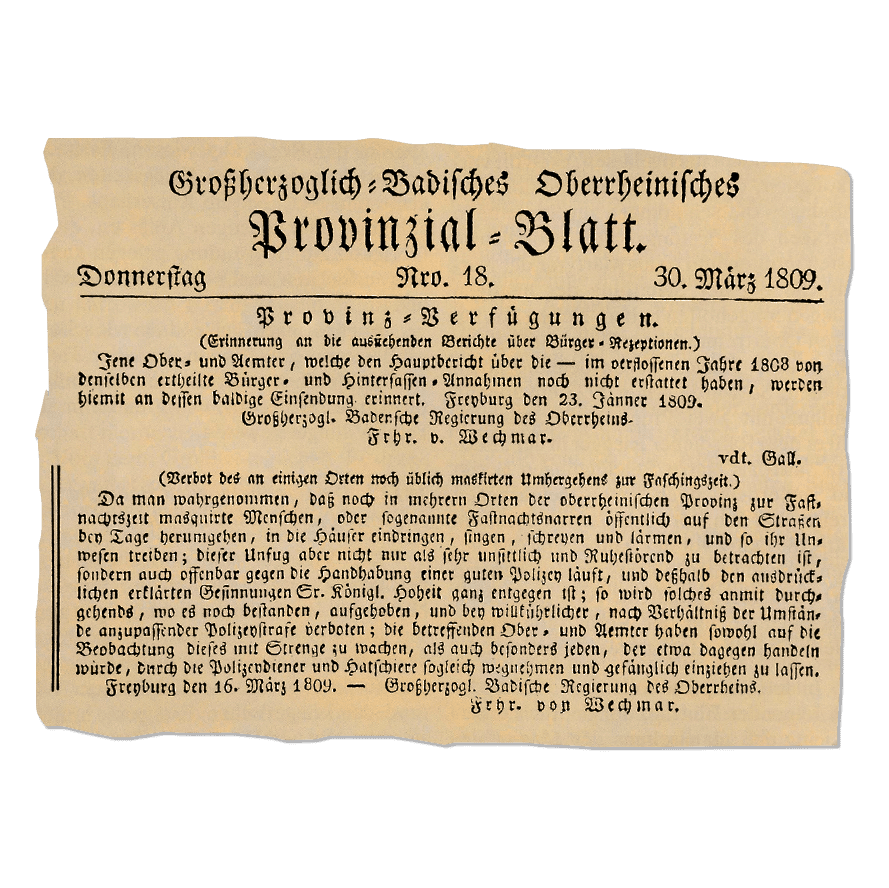

In the southwest, the restoration of the baroque Fastnacht tradition experienced a tremendous upswing from the beginning of the 20th century at the latest – especially because, in a spirit of historicism, prominent individuals were now also enthusiastic about it. Fastnacht became the epitome of local identity, and in former imperial cities it was also a reminder of the sovereignty of the past. In 1924, in response to repeated bans from the governments in Stuttgart and Karlsruhe in the wake of the fragile political situation after 1918, the oldest continually existing Fastnacht group in Germany – the “Vereinigung badisch-württembergischer Narrenzünfte”, later renamed the “Vereinigung schwäbisch-alemannischer Narrenzünfte” (“Association of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht Guilds”) – was constituted in Villingen. A little later, the association also launched the “Narrentreffen” – supra-local “fool’s meetings” to enable them to show their diversity. The first event of this kind took place in 1928.

Poster for the first “Narrentreffen” of the Association of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht Guilds in Freiburg in 1928, designed by Erwin Krumm, Elzach, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

Karneval Remnants in the South

Offenburg is a good example of how long Karneval elements lasted in the southwest. The city, whose “Fasent” (as it is also called in the local dialect) is decidedly Alemannic today, was used to coexisting with the Rhenish forms of festivities as a matter of course until the 1930s. A photo from 1935 shows Offenburg’s Prince Carneval inspecting the troops of the “Ranzengarde” in front of the town hall. A “Ranzengarde” is not only special to Mainz, where it undoubtedly has the highest level of popularity. They also feature in several Fastnacht festivities in southwestern Germany.

“Prince Carneval” leads the “Ranzengarde” in Offenburg in 1935, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

Karneval Remnants in the South

Offenburg is a good example of how long Karneval elements lasted in the southwest. The city, whose “Fasent” (as it is also called in the local dialect) is decidedly Alemannic today, was used to coexisting with the Rhenish forms of festivities as a matter of course until the 1930s. A photo from 1935 shows Offenburg’s Prince Carneval inspecting the troops of the “Ranzengarde” in front of the town hall. A “Ranzengarde” is not only special to Mainz, where it undoubtedly has the highest level of popularity. They also feature in several Fastnacht festivities in southwestern Germany.

“Prince Carneval” leads the “Ranzengarde” in Offenburg in 1935, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

Masquerading on the Danube and Neckar

The characteristic feature of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities today are the masked figures with high-quality wooden face masks that strictly follow the respective local tradition. In some traditional locations, masks that are up to 200 years old are still worn. Figures such as the “Butzen” from Haigerloch are a direct successor of the pre-romantic disguises, which have become somewhat stylised over the course of time and whose basic forms almost all originate from the Baroque era. Few fool figures, however, actually go back that far. In the 20th century in particular, many new guilds emerged that developed their own masks and “Häser” (garments) which were more or less consciously based on classical models. The inflationary growth of the Swabian-Alemannic Fasnet, and the question as to what is “genuine”, “original”, “historical” or even “ancient” about it, has been discussed controversially by experts and scholars almost continuously.

“Haigerlocher Butzen”, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Masquerading on the Danube and Neckar

The characteristic feature of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities today are the masked figures with high-quality wooden face masks that strictly follow the respective local tradition. In some traditional locations, masks that are up to 200 years old are still worn. Figures such as the “Butzen” from Haigerloch are a direct successor of the pre-romantic disguises, which have become somewhat stylised over the course of time and whose basic forms almost all originate from the Baroque era. Few fool figures, however, actually go back that far. In the 20th century in particular, many new guilds emerged that developed their own masks and “Häser” (garments) which were more or less consciously based on classical models. The inflationary growth of the Swabian-Alemannic Fasnet, and the question as to what is “genuine”, “original”, “historical” or even “ancient” about it, has been discussed controversially by experts and scholars almost continuously.

“Haigerlocher Butzen”, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Corps and Guards on the Rhine

The colourful diversity of the Rhenish Karneval – as demonstrated in the Rose Monday processions in Mainz, Düsseldorf, Aachen and Bonn, for example – can hardly be presented in its entirety. In Cologne, there are also the “Schul- und Veedelszöch” (procession groups of the individual schools and districts) that appear on the Sunday. Between the elaborate floats, equestrian groups and foot groups, a characteristic of the main Rose Monday procession are the numerous uniformed participants in the corps and guards. The oldest traditional corps in Cologne is the “Rote Funken”, which dates back to 1823.

Karneval in Cologne, “Rote Funken” at the Severinstorbogen, photo: Vera Drewke

Corps and Guards on the Rhine

The colourful diversity of the Rhenish Karneval – as demonstrated in the Rose Monday processions in Mainz, Düsseldorf, Aachen and Bonn, for example – can hardly be presented in its entirety. In Cologne, there are also the “Schul- und Veedelszöch” (procession groups of the individual schools and districts) that appear on the Sunday. Between the elaborate floats, equestrian groups and foot groups, a characteristic of the main Rose Monday procession are the numerous uniformed participants in the corps and guards. The oldest traditional corps in Cologne is the “Rote Funken”, which dates back to 1823.

Karneval in Cologne, “Rote Funken” at the Severinstorbogen, photo: Vera Drewke

Imperial City Colours All Over

The big Karneval metropolis of Cologne on the Rhine, and the small fool’s nest of Rottweil on the Neckar, could hardly be more different. And yet there is a similarity between the two in the “fifth season”, which reveals the same desires hidden behind both Fastnacht and Karneval. Both places – 500 kilometres apart – were once free imperial cities. And this history is remembered by both during the festivities. In Cologne, the “Funken” of 1823 still wear the colours of the imperial city (red and white), and in Rottweil, the leader of the fools (the “Narrenengel”, or “angel of fools”) also dons red and white and represents a figure documented as early as during the era of the city’s imperial status. The Cologne “Jecken” and the Rottweil “Narren”, then, share much in common thanks to their cultural memory.

“Narrenengel” in Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele; “Rote Funken” in Cologne, photo: Daniel Rüdell

#visitblackforest Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht, video: Chris Keller, Schwarzwaldtourismus Chris Keller / Schwarzwald Tourismus

#visitblackforest Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht, video: Chris Keller, Schwarzwaldtourismus Chris Keller / Schwarzwald Tourismus

http://www.deiters.de – Cologne Karneval, Rose Monday 2019, video: Mathias Amling, deiters Mathias Amling / deiters - ROSENMONTAG 2019 - DER FILM

http://www.deiters.de – Cologne Karneval, Rose Monday 2019, video: Mathias Amling, deiters Mathias Amling / deiters - ROSENMONTAG 2019 - DER FILM