Dates and Times

35-Day Timeframe

Given Fastnacht probably stems from much older ancestral festivities at the transition from winter to spring – and possibly also from festivities at the turn of the year deriving from the Roman calendar, which may be regarded as predecessors – it moves within the Christian calendar in the period between the beginning of February and the first week of March. Its date is not fixed because the start of Lent depends on the date of Easter, which changes annually and can vary by up to 35 days. Ash Wednesday also shifts as a result. In what were once very popular pictures of the months, used to visualise the characteristics of the individual months, a Fastnacht motif was therefore usually chosen as the picture for February. This was the case for Matthäus Merian in 1622 as well, who also saw Fastnacht festivities as the most important event of “Hornung” (that is, February).

Picture of February. Etching by Matthäus Merian, from: The Twelve Months with Verses, Aubry, Strasbourg 1622, Etching, Brunswick, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Inventory No. MMerian AB 3.96

Easter-Dependent

In 325, under the reign of Emperor Constantine I (his portrait head from a colossal statue shown here), the Council of Nicaea – following the Jewish lunar calendar – set the date of Easter for the first Sunday after the spring full moon. This meant that the date of Easter could fluctuate in a timeframe of 28 days – a lunar phase – and then 7 more days, depending on the position of the full moon. And by the same token, all dates dependent on Easter were also movable: The beginning of the pre-Easter Lent period, as well as the dates of the subsequent feasts of Ascension on the 40th day and Pentecost on the 50th day after Easter. As such, the Christian year is still “lunisolar” to this day – partly oriented to the sun, and partly to the moon. The fixed dates of the Christmas Season depend on the sun, the moving dates of the Easter Season on the moon. Accordingly, Fastnacht also falls on a different date every year.

Constantine the Great (270/88 – 337), Head of a colossal statue, Rome, Capitoline Museums

Annual Cycle Explanations

The animation shows the fixed and movable festive seasons of the Christian year. Since Easter Sunday has been scheduled, since the Council of Nicaea (325 AD), on the Sunday after the spring full moon – if the latter falls on a Sunday. Easter is on the Sunday after – the time window for the Easter date is 35 days. That is the duration of a lunar phase of 28 days plus a maximum of 7 more days. This means that Easter cannot be before 22 March and not after 25 April. The flexible dates of Fastnacht, Ascension Day, Pentecost and Corpus Christi are based on Easter’s flexibility.

Earliest and latest possible date of the movable festivals:

| Rose Monday | ((= 48th day before Easter) | 02 Feb – 08 Mar |

| Ash Wednesday | ((= 46th day before Easter) | 04 Feb – 10 Mar |

| Easter Sunday | – | 22 Mar – 25 Apr |

| Ascension Day | ((= 40th day after Easter) | 01 May – 04 Jun |

| Pentecost | ((= 50th day after Easter) | 11 May – 14 Jun |

| Corpus Christi | ((= 60th day after Easter) | 21 May – 24 Jun |

These dates are for any given normal year. For leap years, the formula “n plus 1” applies to the dates before 29 February, given they have to be calculated backwards from the date of Easter. So, while the earliest date for Rose Monday in a leap year is 3 February (as opposed to 2 February), its latest possible date is always 8 March. The leap year does not affect the time window of Ascension Day, Pentecost and Corpus Christi, as they all fall after 29 February.

Although Lent is 40 days long, Ash Wednesday is the 46th day before Easter (not the 40th). This is due to the fact that, according to a regulation of the Synod of Benevento (1091), the 6 Sundays before Easter are not considered fasting days, and so the beginning of fasting is 6 days earlier. In a few regions and dioceses where the Benevento regulation does not apply and Sundays also count as fasting days, fasting then begins 6 days later. Accordingly, Fastnacht is also celebrated there a week later. Examples of this are the “Old Fastnacht” or “Bauernfastnacht” (“Farmers’ Carnival”) in the Basel area or the “Ambrosian Carnival” in the diocese of Milan, whose liturgy, supposedly going back to St. Ambrose, follows the pre-benevent fasting tradition.

Highlighted in yellow:

All dates on which regionally different Fastnacht or Fastnacht-like customs are practised.

Thursday Start for Fastnacht

Fastnacht, with its main events, lasts for just under a week. Its first day is the Thursday before Ash Wednesday, when slaughtering and baking in fat took place – hence why it is called “Schmotziger Donnerstag” (“Fat Thursday”, from Alemannic “Schmotz” meaning “fat”) in the Swabian-Alemannic region. In many places it marks the start of Fasnet, and in the Hegau-Bodensee region it is even Fasnet’s main event. In Waldshut, this is the day when the “Geltentrommler” can be seen and heard: White-clad men with faces whitened with flour, drumming with wooden spoons on upside-down wooden wash tubs loudly announcing the start of Fasnet. In the Rhineland, Thursday is known as “Weiberfastnacht” (“Women’s Carnival”) because it is a day when women’s rights are enforced.

Fat Thursday: “Geltentrommler” in Waldshut, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Thursday Start for Fastnacht

Fastnacht, with its main events, lasts for just under a week. Its first day is the Thursday before Ash Wednesday, when slaughtering and baking in fat took place – hence why it is called “Schmotziger Donnerstag” (“Fat Thursday”, from Alemannic “Schmotz” meaning “fat”) in the Swabian-Alemannic region. In many places it marks the start of Fasnet, and in the Hegau-Bodensee region it is even Fasnet’s main event. In Waldshut, this is the day when the “Geltentrommler” can be seen and heard: White-clad men with faces whitened with flour, drumming with wooden spoons on upside-down wooden wash tubs loudly announcing the start of Fasnet. In the Rhineland, Thursday is known as “Weiberfastnacht” (“Women’s Carnival”) because it is a day when women’s rights are enforced.

Fat Thursday: “Geltentrommler” in Waldshut, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Monday as the Main Day

Friday as the day of Christ’s death, and Saturday (and also Sunday) as the Lord’s Day, are not traditional Fastnacht days – although Sunday now also sees Fastnacht played out on the street. Fastnacht’s main day is Monday, called “Rosenmontag” (Rose Monday) in the Rhineland and “Fasnetmentig” (“Fasnet Monday”) in the Swabian-Alemannic region. As the big Rose Monday parades move through the streets of Cologne, Mainz, Düsseldorf, Aachen and many other cities in the Rhineland, in southwestern Germany the masked parades, also called “Narrensprünge” (“Fool’s Jumps”), take place. Probably the best known of these is in Rottweil, which starts at 8 am at the Schwarzes Tor.

Shrove Monday: “Narrensprung” in Rottweil, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Conclusion on Tuesday

On Shrove Tuesday – known as “Veilchendienstag” in the Rhineland – the festivities in the Fastnacht strongholds begin to settle down, while in the southwest more activity can be seen and heard, and many parades take place. Tuesday sees a final, albeit somewhat melancholy, climax as night falls and Ash Wednesday draws closer. Then, in many places, Fastnacht is burned, drowned or buried in the form of a symbolic figure. In addition to this (or alongside it), there is an abundance of night-time mourning rituals in the Rhineland, as well as in the south. In Cologne, the farewell event is the burning of the “Nubbel”, a puppet that personifies the days of the festivities. And 500 km further south, in Bad Säckingen on the Upper Rhine, for example, the “Hüüler” (howlers) wander around grieving with their torches, searching in vain for Fastnacht – which has now disappeared – in every corner. But after Fastnacht is also before Fastnacht. The jesters console themselves with the fact that, from midnight on Shrove Tuesday, the next Fastnacht is just around the corner.

Shrove Tuesday Eve: “Hüüler” in Bad Säckingen, photo: Gerhard Rohrer

Conclusion on Tuesday

On Shrove Tuesday – known as “Veilchendienstag” in the Rhineland – the festivities in the Fastnacht strongholds begin to settle down, while in the southwest more activity can be seen and heard, and many parades take place. Tuesday sees a final, albeit somewhat melancholy, climax as night falls and Ash Wednesday draws closer. Then, in many places, Fastnacht is burned, drowned or buried in the form of a symbolic figure. In addition to this (or alongside it), there is an abundance of night-time mourning rituals in the Rhineland, as well as in the south. In Cologne, the farewell event is the burning of the “Nubbel”, a puppet that personifies the days of the festivities. And 500 km further south, in Bad Säckingen on the Upper Rhine, for example, the “Hüüler” (howlers) wander around grieving with their torches, searching in vain for Fastnacht – which has now disappeared – in every corner. But after Fastnacht is also before Fastnacht. The jesters console themselves with the fact that, from midnight on Shrove Tuesday, the next Fastnacht is just around the corner.

Shrove Tuesday Eve: “Hüüler” in Bad Säckingen, photo: Gerhard Rohrer

Sorrow on Ash Wednesday

Ash Wednesday officially marks the beginning of Lent, something which is clearly underlined in the Catholic Church by the transience ritual of the ash cross. Despite that, quite a number of participants still say goodbye to Fasnet in a sociable way, even on this day. In many places in southern Germany, people meet on Ash Wednesday evening to eat snails or fish together. And in some Fastnacht strongholds, “Geldbeutelwäsche” (“purse laundering”) is still practised as a humorous aftermath of the festivities. One of the places that have developed a particularly unique tradition here is Wolfach in the Kinzigtal, in the German federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Fastnacht revellers – dressed in black mourning attire and wearing top hats – throw their empty purses and wallets into the well to clean them, moaning loudly. They then continue their lament along the outer wall of the local tax office, which, in Wolfach, is appropriately called the “Wailing Wall”. Anyone caught being remotely happy, instead of remaining deadly serious, is obliged to pay for a round afterwards.

Ash Wednesday: “Geldbeutelwäsche” in Wolfach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Sorrow on Ash Wednesday

Ash Wednesday officially marks the beginning of Lent, something which is clearly underlined in the Catholic Church by the transience ritual of the ash cross. Despite that, quite a number of participants still say goodbye to Fasnet in a sociable way, even on this day. In many places in southern Germany, people meet on Ash Wednesday evening to eat snails or fish together. And in some Fastnacht strongholds, “Geldbeutelwäsche” (“purse laundering”) is still practised as a humorous aftermath of the festivities. One of the places that have developed a particularly unique tradition here is Wolfach in the Kinzigtal, in the German federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. Fastnacht revellers – dressed in black mourning attire and wearing top hats – throw their empty purses and wallets into the well to clean them, moaning loudly. They then continue their lament along the outer wall of the local tax office, which, in Wolfach, is appropriately called the “Wailing Wall”. Anyone caught being remotely happy, instead of remaining deadly serious, is obliged to pay for a round afterwards.

Ash Wednesday: “Geldbeutelwäsche” in Wolfach, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Lent Illustrated

Six weeks of fasting is a long time. For generations, this has always given people of faith cause to visualise the Lent period. The scholarly Count Wilhelm Werner von Zimmern did this in around 1560 in a private devotional book illustrated by himself. In it, starting at the bottom left, he depicted Lent as a broad oval, which recorded each individual day of fasting and in which Sundays were each highlighted as medallions. At the top on the apex, for example, you could see Laetare Sunday – also known as Rose Sunday, because it was a day on which the Pope always presented a golden rose to a deserving person. On the lower right, there is Palm Sunday – with the image of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem – and finally, at the bottom in a round arch, Easter Sunday, with Christ rising from the dead. This made it easier to visualise the stages of Lent, and helped people learn more about Lent itself.

Wilhelm Werner von Zimmern: Representation of Lent, coloured drawing in the Count’s private devotional book, circa 1560, Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don, A III 54, fol. 231 v.

One Foot Less Every Week

In Catalonia, a very simple and common way of imagining Lent for children is the “Vella de Cuaresma”. Here, Lent is personified as a woman with seven feet. Before each weekend of Lent, one of her feet can be cut off – and once she has been completely amputated, Easter will have arrived. The representation of the “Vella de Cuaresma” in Catalan costume shown here dates from the 18th century. In numerous modern variations, however, she can be downloaded from the internet – often with a whole collection of shoes on her seven feet. As a colourful cardboard figure that loses a foot every week, no Catalan kindergarten or primary school should be without her when Ash Wednesday begins.

Vella de Cuaresma with seven feet, Catalonia, 18th century

One Foot Less Every Week

In Catalonia, a very simple and common way of imagining Lent for children is the “Vella de Cuaresma”. Here, Lent is personified as a woman with seven feet. Before each weekend of Lent, one of her feet can be cut off – and once she has been completely amputated, Easter will have arrived. The representation of the “Vella de Cuaresma” in Catalan costume shown here dates from the 18th century. In numerous modern variations, however, she can be downloaded from the internet – often with a whole collection of shoes on her seven feet. As a colourful cardboard figure that loses a foot every week, no Catalan kindergarten or primary school should be without her when Ash Wednesday begins.

Vella de Cuaresma with seven feet, Catalonia, 18th century

Prelude to Fastnacht: St. Martin’s Day (11 November)

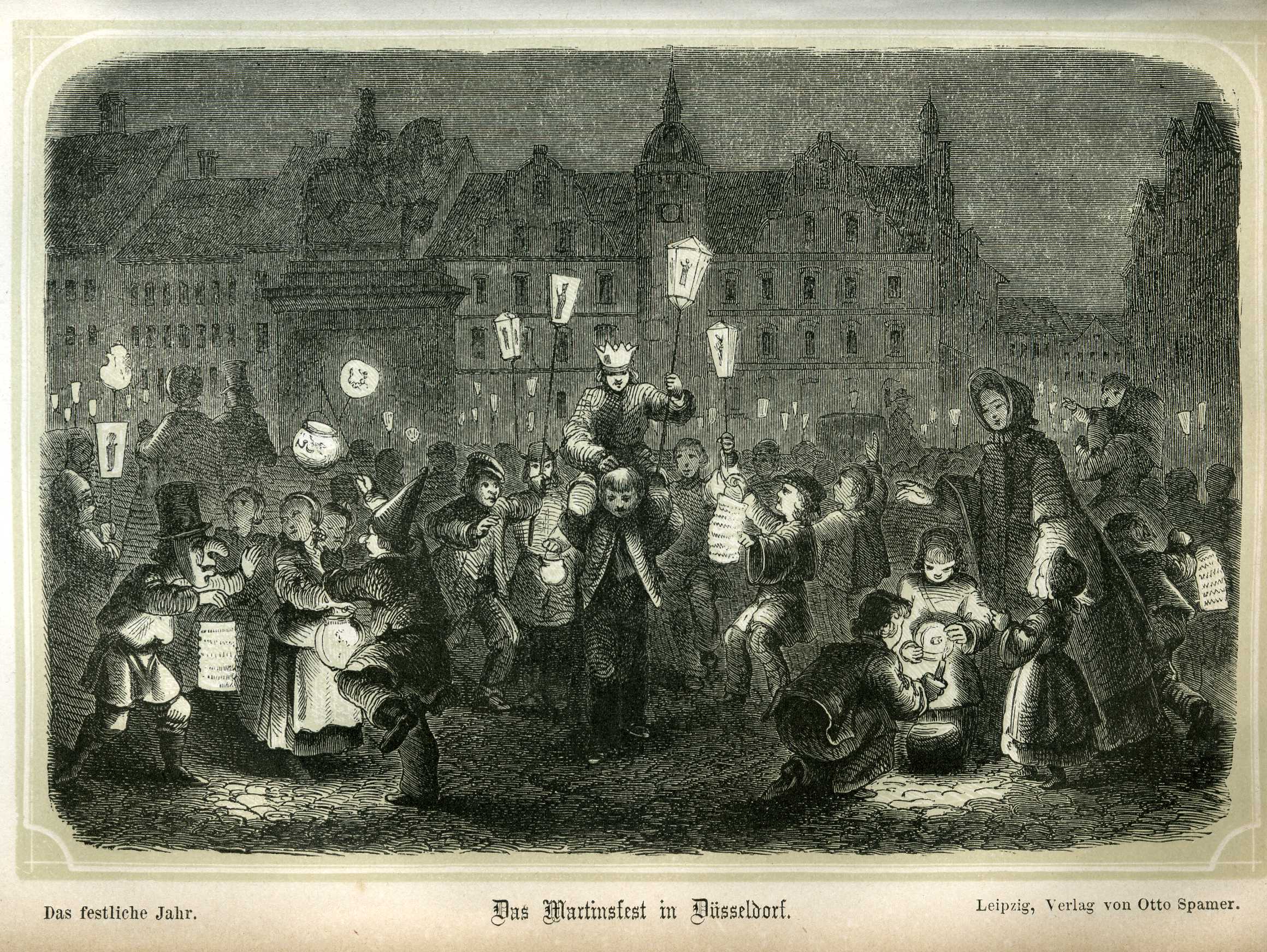

When looking at the dates before Fastnacht actually gets underway, the first prelude to the foolish season of the coming year is St. Martin’s Day, on 11 November. Because St. Martin’s Day used to be the last opportunity for lavish celebrations before the Christmas fasting period that what was once customary, this date also served the role of a “Fastelovend” – an evening before fasting. St. Martin’s Day, as a prelude to Fastnacht, is particularly widespread in the Rhineland, where the veneration of St Martin also has a deep history. A 19th century wood engraving of St. Martin’s Day in Düsseldorf shows children with St. Martin lanterns, and the first masked people mingling on St. Martin’s Eve. Today, 11 November is a day of exuberant carnivalesque celebration, with thousands of revellers gathering at 11.11 am on the dot. In southern Germany, celebrating 11 November as a prelude to Fastnacht is less common – although a manuscript from the Schussenried Monastery referred to St. Martin’s Day as “Advent Carnival” as early as during the Baroque period.

St. Martin’s Day (11 November): St. Martin’s festival in Düsseldorf, wood engraving from Otto von Reinsberg-Düringsfeld: “Das festliche Jahr”, Leipzig / Barsdorf 1898

Kick-Off on Epiphany (6 January)

In southwestern Germany, Epiphany on 6 January is considered the start of the Fastnacht season. Here, “cleaners” go from house to house in many Fastnacht towns in the Swabian-Alemannic region and symbolically remove the dust of months past from the masks and costumes that have been lying in cupboards and chests throughout the year. It may well be the case that they encounter the carol singers in one house or another.

Epiphany (6 January): “Abstauber” (“dusters”) in Dietingen near Rottweil, photo: Schwarzwälder Bote

Kick-Off on Epiphany (6 January)

In southwestern Germany, Epiphany on 6 January is considered the start of the Fastnacht season. Here, “cleaners” go from house to house in many Fastnacht towns in the Swabian-Alemannic region and symbolically remove the dust of months past from the masks and costumes that have been lying in cupboards and chests throughout the year. It may well be the case that they encounter the carol singers in one house or another.

Epiphany (6 January): “Abstauber” (“dusters”) in Dietingen near Rottweil, photo: Schwarzwälder Bote

The Bean King on Epiphany

The commemoration day of the three holy kings was, and still is, also customary in the Lower Rhine region as a kick-off to Fastnacht. In the Netherlands, the festival of the Bean King was celebrated on this day – also known by the religious name “Epiphany”, which is documented by many paintings (especially from the 17th century). Here is an example by the Antwerp painter Jacob Jordaens. On 6 January, a bean seed was baked into a cake. Whoever found it in their piece of the cake was crowned and celebrated as a random king, complete with a paper crown. Everyone had to toast the Bean King – who was also given a jester at their side – with the expression “The king is drinking”. In France, it is still customary to eat the “galette des rois” – the kings’ cake – on Epiphany. A small clay figure is now baked into the cake, but it still bears the name “fève” (bean). Whoever finds it in their piece of the cake is also symbolically made king with a paper crown.

Festival of the Bean King on 6 January, painting by Jacob Jordaens (between 1635 and 1655) Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, GK 8

The Bean King on Epiphany

The commemoration day of the three holy kings was, and still is, also customary in the Lower Rhine region as a kick-off to Fastnacht. In the Netherlands, the festival of the Bean King was celebrated on this day – also known by the religious name “Epiphany”, which is documented by many paintings (especially from the 17th century). Here is an example by the Antwerp painter Jacob Jordaens. On 6 January, a bean seed was baked into a cake. Whoever found it in their piece of the cake was crowned and celebrated as a random king, complete with a paper crown. Everyone had to toast the Bean King – who was also given a jester at their side – with the expression “The king is drinking”. In France, it is still customary to eat the “galette des rois” – the kings’ cake – on Epiphany. A small clay figure is now baked into the cake, but it still bears the name “fève” (bean). Whoever finds it in their piece of the cake is also symbolically made king with a paper crown.

Festival of the Bean King on 6 January, painting by Jacob Jordaens (between 1635 and 1655) Kassel, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, GK 8

Foolishness on Candlemas (2 February)

Candlemas, celebrated on 2 February, also has an element of Fastnacht tradition – not least in southern Europe (like in Spain, for example). This day, theologically speaking, finally brings the Christmas Season to a close. In Catholic churches, Nativity scenes are put away on 2 February. From a Fastnacht point of view, there is another peculiarity of the German-speaking countries: Given Fastnacht traditions did not completely die out in all the areas that eventually became Protestant, some Protestant rulers endeavoured to limit festivities to at least one day, and to set them on a fixed date. The fact that a Catholic Marian feast day – Candlemas – was chosen for this was certainly no coincidence. Probably the most prominent Fastnacht tradition that was shifted to Candlemas has survived in Spergau, near Merseburg in the German federal state of Saxony-Anhalt. Today, though, the “Spergemer Lichtmess” – with its numerous original figures, such as the pea bears – no longer takes place on 2 February itself, but instead on the nearest Sunday.

Pea bears at Candlemas in Spergau near Merseburg, photo: Ulrich Kneise with the kind permission of the Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Halle/Saale

Fastnacht beyond Ash Wednesday

Another special event is “Alte Fasnet” (“Old Fasnet”), or “Buurefasnet” (“Farmers’ Carnival”), which begins on the weekend (or on the Monday) after Ash Wednesday. It is celebrated along the High Rhine and in parts of the Markgräflerland. Basel is its stronghold. The delayed date is not due to any calendar reform, as is often incorrectly claimed. It is based on an older calculation of Lent: While, originally, Sundays were also counted as fasting days, they were later exempted from fasting almost everywhere – which is why Ash Wednesday today is 46 days before Easter, rather than 40. But in areas where the old calculation was retained (with Sundays still counted as fasting days) – for example in the Basel region or in the Diocese of Milan – the beginning of Lent is a week closer to Easter, and thus behind today’s Ash Wednesday. This explains the term “Alte Fasnet” (“Old Fasnet”). Any other reason seeking to explain why Protestant Basel, of all places, celebrates Fastnacht to such an extent is going too far.

Monday after Ash Wednesday: Basel Fasnacht, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Fastnacht beyond Ash Wednesday

Another special event is “Alte Fasnet” (“Old Fasnet”), or “Buurefasnet” (“Farmers’ Carnival”), which begins on the weekend (or on the Monday) after Ash Wednesday. It is celebrated along the High Rhine and in parts of the Markgräflerland. Basel is its stronghold. The delayed date is not due to any calendar reform, as is often incorrectly claimed. It is based on an older calculation of Lent: While, originally, Sundays were also counted as fasting days, they were later exempted from fasting almost everywhere – which is why Ash Wednesday today is 46 days before Easter, rather than 40. But in areas where the old calculation was retained (with Sundays still counted as fasting days) – for example in the Basel region or in the Diocese of Milan – the beginning of Lent is a week closer to Easter, and thus behind today’s Ash Wednesday. This explains the term “Alte Fasnet” (“Old Fasnet”). Any other reason seeking to explain why Protestant Basel, of all places, celebrates Fastnacht to such an extent is going too far.

Monday after Ash Wednesday: Basel Fasnacht, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Fasnacht in the Middle of Lent

The last possible date used for Fastnacht is Laetare Sunday, the fourth Sunday of Lent, which also marks the middle of Lent. The fact that, on this day, you were allowed to show some anticipation for Easter can be detected in the word “Laetare” itself, which means “rejoice”. In many regions of Europe, the midway point of Lent (Dutch “halfvasten”, French “mi-carême”, Italian “mezzaquaresima”) is celebrated with joyful traditions. In central Italy, for example, a witch-like symbolic figure of Lent is sawn in half (“segar la vecchia”). In parts of the French-speaking world, however, it even became customary to celebrate Fastnacht on Mid-Lent. The largest “carnaval du mi-carême” to date has survived in Wallonia, in the East Belgian town of Stavelot. There, the day belongs to the “blanc moussis” who, with their white hooded shirts, long-nosed masks and pig bladders, somewhat resemble the “Hemdglonker” found in the German southwest. After Laetare, the period for traditional Fastnacht festivities finally comes to an end.

Laetare Sunday: “Blanc Moussis” in Stavelot, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de

Fasnacht in the Middle of Lent

The last possible date used for Fastnacht is Laetare Sunday, the fourth Sunday of Lent, which also marks the middle of Lent. The fact that, on this day, you were allowed to show some anticipation for Easter can be detected in the word “Laetare” itself, which means “rejoice”. In many regions of Europe, the midway point of Lent (Dutch “halfvasten”, French “mi-carême”, Italian “mezzaquaresima”) is celebrated with joyful traditions. In central Italy, for example, a witch-like symbolic figure of Lent is sawn in half (“segar la vecchia”). In parts of the French-speaking world, however, it even became customary to celebrate Fastnacht on Mid-Lent. The largest “carnaval du mi-carême” to date has survived in Wallonia, in the East Belgian town of Stavelot. There, the day belongs to the “blanc moussis” who, with their white hooded shirts, long-nosed masks and pig bladders, somewhat resemble the “Hemdglonker” found in the German southwest. After Laetare, the period for traditional Fastnacht festivities finally comes to an end.

Laetare Sunday: “Blanc Moussis” in Stavelot, photo: Ralf Siegele www.ralfsiegele.de