The Jester’s Attributes 1

The Marotte: A Reflection of its Bearer

From around 1250 to 1480, the figure of the fool developed in the visual arts, and probably also in reality, into a fixed type with very specific external characteristics and attributes. Quite a few of them are still part of the look of Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht figures today, albeit in a partly altered form. The fool’s oldest feature, which appears as early as in the miniatures of the 13th century Psalter manuscripts, is a simple wooden club, or cudgel. As early as the 14th century, the club refined into a sceptre with a carved little head on top, which was called a “marotte” in French, derived from “marionette”, meaning “little doll”. The woodcut of a fully formed jester with a striking physical appearance from around 1540 by Hans Vogtherr the Younger also shows that the head on the marotte was not just any face – it was the exact likeness of its bearer.

Jester with marotte, woodcut by Heinrich Vogtherr the Younger, circa 1540, coloured copy, Gotha Sammlungen des Schlossmuseums, Inv. No. 40, 18; A. K. No. xyl. II, 50

The Marotte’s Life of its Own

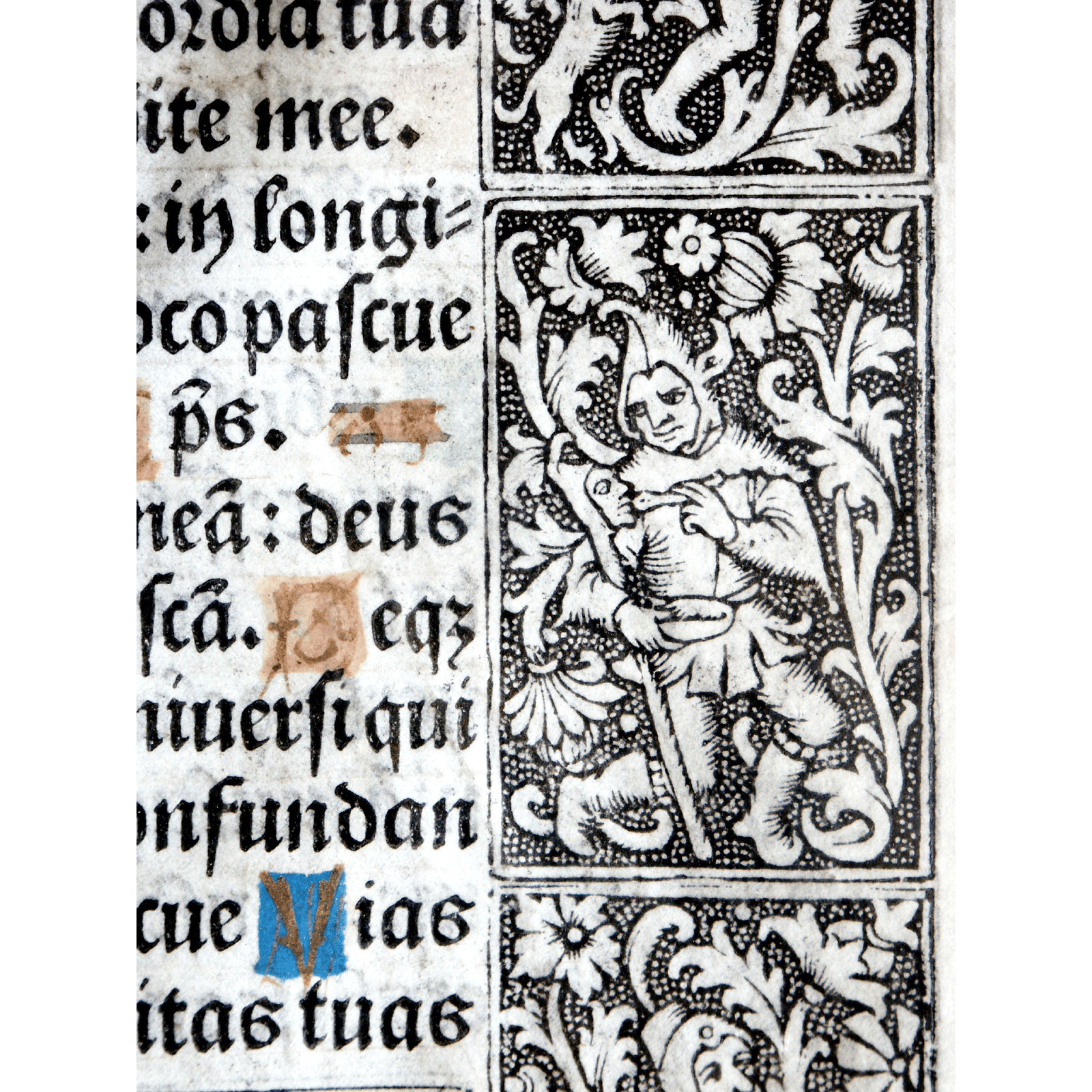

In some early modern depictions of jesters, the marotte seems to take on a life of its own. A border to a French book of hours printed on parchment from around 1510 shows a jester feeding his seemingly hungry marotte with a wooden spoon of jester’s food. Interestingly, an idiom still common in German today, which uses the word “Marotte” to mean “quirk”, is derived from the jester’s egocentric preoccupation with his sceptre.

Jester feeds his marotte with a spoon, detail from the borders of a book of hours printed on parchment from Gilbert Hardouyn’s printer and publisher, Paris, circa 1510, single sheet, private collection

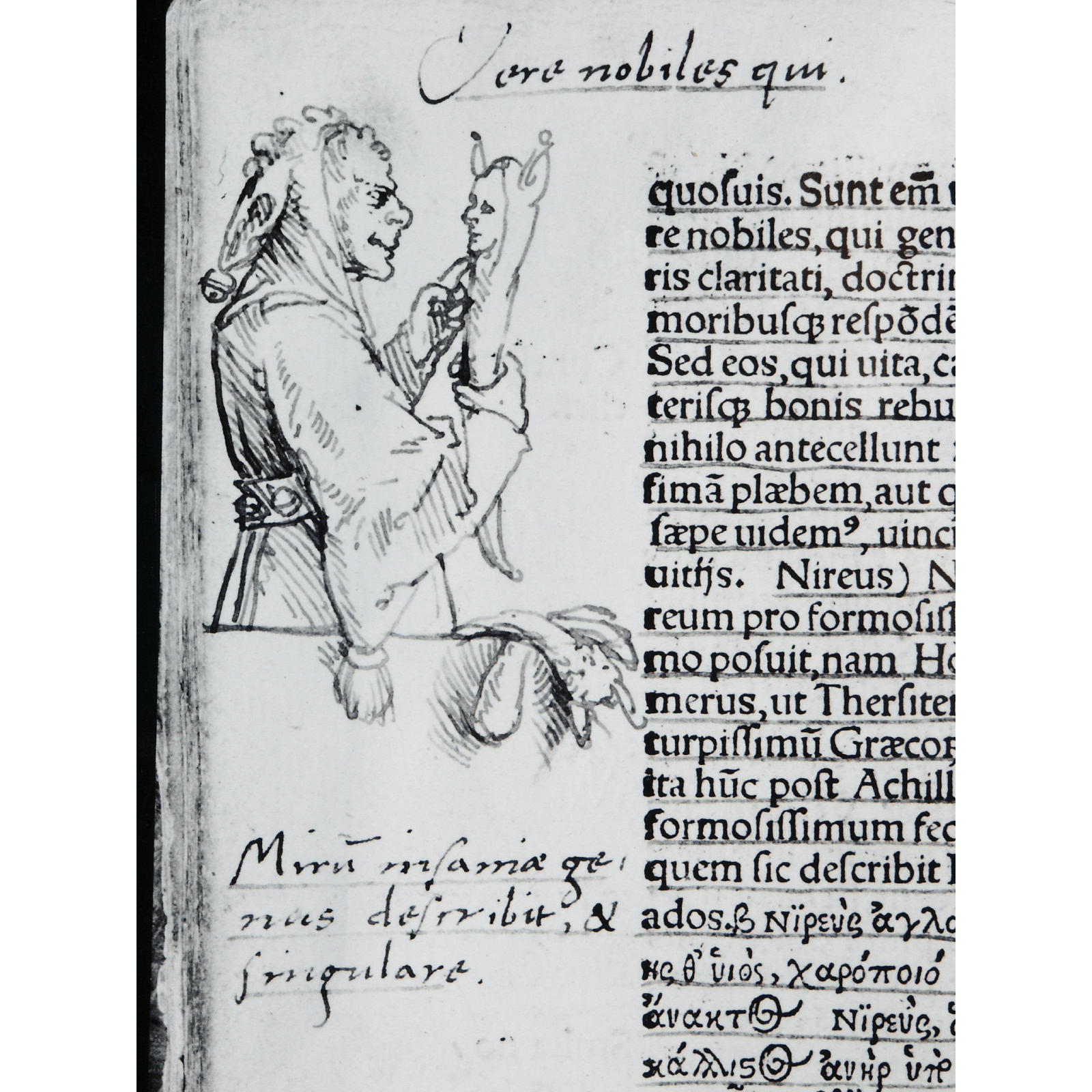

Conversation with the Marotte

A 1515/16 peripheral drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger to a copy of Erasmus of Rotterdam’s “In Praise of Folly” printed in Basel and owned by the humanist Oswald Myconius shows a fool intensely preoccupied with his marotte. He appears to stroke the marotte’s chin, and have an intimate conversation with it. This bizarre conversation between the jester and his own image – a dialogue with himself – was meant to visualise the jester’s narcissistic self-love. As an ignoramus of the divine world order, incapable of love of God (“amor Dei” in Latin), and therefore also incapable of selfless Christian charity, the jester only knows “amor sui” – the infatuation with his own ego.

Jester with a marotte, border drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger (1515/16) for the “Erasmi Roterodami Stulititae Laus”, Basel 1515, fol. K 4 v., Basel, Kunstmuseum, Inv. No. 1662.166

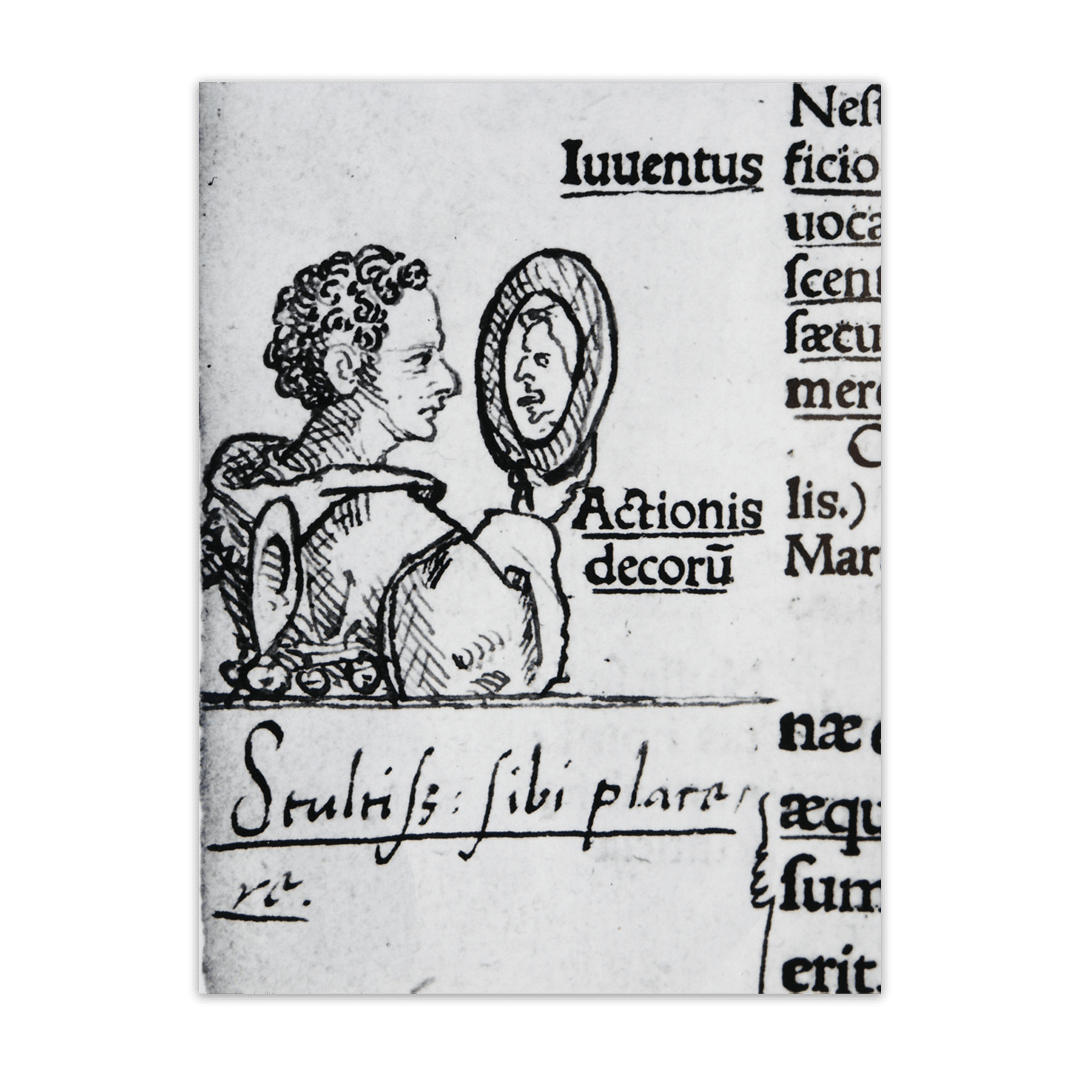

From the Marotte to the Mirror

The marotte as a symbol of self-absorption then leads directly to the jester’s mirror, which Hans Holbein also explored in his peripheral drawings to Erasmus of Rotterdam’s “In Praise of Folly”: A jester looks at himself in the mirror, while his likeness teasingly sticks out his tongue. “Stultitia sibi placet” is inscribed in handwriting underneath: “Foolishness pleases itself.” This hints at the later double function of the jester’s mirror, which can also be turned upside down and held up to others to show them their wrongness. In this way, the mirror proves to be ambivalent: Turned towards the bearer, it can be the epitome of personal vanity and pathological egotism. But turned towards the other person or the world, it can also serve as a moral medium for recognising one’s own faults. In this second function, the mirror is then part of the foolish right of complaint.

Jester with mirror, border drawing by Hans Holbein the Younger (1515/16) for the “Erasmi Roterodami Stulititae Laus”, Basel 1515, fol. E 2 v., Basel, Kunstmuseum, Inv. No. 1662.166

Vanity and Self-Awareness

An anonymous Dutch copperplate engraving from the 17th century addresses the motif of the jester’s mirror in its ambiguity. A well-dressed, beautiful female looks vainly into a mirror – but an ugly jester has crept up on her from behind unnoticed, and is also peering out of the same mirror close beside her. Here, then, the mirror is both a narcissistic attribute as well as an instrument of sobering self-awareness all in one.

Woman with a mirror and a fool, anonymous Dutch copper engraving, 1st quarter of the 17th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-P-OB 77.716

Vanity and Self-Awareness

An anonymous Dutch copperplate engraving from the 17th century addresses the motif of the jester’s mirror in its ambiguity. A well-dressed, beautiful female looks vainly into a mirror – but an ugly jester has crept up on her from behind unnoticed, and is also peering out of the same mirror close beside her. Here, then, the mirror is both a narcissistic attribute as well as an instrument of sobering self-awareness all in one.

Woman with a mirror and a fool, anonymous Dutch copper engraving, 1st quarter of the 17th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-P-OB 77.716

Echoes of the Marotte in Traditional Customs

If we ask what remains of the marotte and mirror during the Fastnacht of southwestern Germany, we find that the classic jester’s sceptre, topped with a head, has been lost in its original form – apart from a few revivals in individual figures from more recent times. However, the basic cudgel and the earlier club still live on in various forms. Examples include the wooden sabres or swords of some “Weissnarren” (“white jesters”) types (a jester figure seen during some Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities on the Baar) and, to a certain extent, probably also in the neck instrument of the slapstick (which is likely to have been adopted primarily from Italian models, though).

“Villinger Narro” with wooden sabre, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Survival of the Mirror in Traditional

The mirror has had a relatively continuous tradition in the Fastnacht figures of southwestern Germany and Tyrol. Although larger hand mirrors are rarely carried as props, small diamond-shaped mirrors, or other designs, often appear as ornaments on Swabian-Alemannic white jesters or on “Fransenkleider” (“fringe dresses”), where they are usually attached to the headpiece or the side border of the face mask – something known as the “Kränzchen” (“little crown”). However, the mirror motif appears most prominently in a series of masked figures during Fastnacht festivities in Tyrol. There, mirrors up to the size of a hand form the central eye-catcher in the middle of the elaborate, horizontally worn headdress, which in Imst, for example, is called the “Schein” (meaning “sham”). The feather-tipped headdress with the mirror in the center of what is called a “Altartuxer” or “Spiegetuxer” in Thaur, a village near Innsbruck, has an almost oversized shape.

“Altartuxer” with mirror headdress from Thaur/Tyrol, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Survival of the Mirror in Traditional

The mirror has had a relatively continuous tradition in the Fastnacht figures of southwestern Germany and Tyrol. Although larger hand mirrors are rarely carried as props, small diamond-shaped mirrors, or other designs, often appear as ornaments on Swabian-Alemannic white jesters or on “Fransenkleider” (“fringe dresses”), where they are usually attached to the headpiece or the side border of the face mask – something known as the “Kränzchen” (“little crown”). However, the mirror motif appears most prominently in a series of masked figures during Fastnacht festivities in Tyrol. There, mirrors up to the size of a hand form the central eye-catcher in the middle of the elaborate, horizontally worn headdress, which in Imst, for example, is called the “Schein” (meaning “sham”). The feather-tipped headdress with the mirror in the center of what is called a “Altartuxer” or “Spiegetuxer” in Thaur, a village near Innsbruck, has an almost oversized shape.

“Altartuxer” with mirror headdress from Thaur/Tyrol, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Ambiguous Symbol: The Sausage

As early as the 16th century, the jester’s cudgel was sometimes replaced by another, deliberately ambiguous motif: a sausage. This, on the one hand, reminded us of the jester’s lavish consumption of meat, but on the other hand (and above all), it was also intended to indicate that the jesters lived their lives “secundum carnem” – that is, in a sexually permissive way. A small-format copperplate engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham from Nuremberg alludes to this quite bluntly, showing a male and female jester with very lewd symbols. The female jester shows her counterpart an open vase, while the male jester holds a jester’s sausage in his hand. Both clearly have a phallic form. “Sausage” was a common vulgar term for the male appendage at the time.

Male and female jester, small-format copper engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham, Nuremberg, 1st half of the 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-B-OB 10.929

Ambiguous Symbol: The Sausage

As early as the 16th century, the jester’s cudgel was sometimes replaced by another, deliberately ambiguous motif: a sausage. This, on the one hand, reminded us of the jester’s lavish consumption of meat, but on the other hand (and above all), it was also intended to indicate that the jesters lived their lives “secundum carnem” – that is, in a sexually permissive way. A small-format copperplate engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham from Nuremberg alludes to this quite bluntly, showing a male and female jester with very lewd symbols. The female jester shows her counterpart an open vase, while the male jester holds a jester’s sausage in his hand. Both clearly have a phallic form. “Sausage” was a common vulgar term for the male appendage at the time.

Male and female jester, small-format copper engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham, Nuremberg, 1st half of the 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-B-OB 10.929

The Jester’s Saugsage in Traditional Customs

The sausage as a reference to the permitted consumption of meat during Fastnacht, but also as an allusion to the sexual desire of the jesters, appears as a prop in some masquerade figures in Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities. The figures “Biss”, “Gschell” and “Fransenkleid” in Rottweil, for example, each carry this kind of leather sausage replica – literally called “Narrenwurst” (“jester’s sausage”) – and which serves as a pointing instrument, or to tease people. The figures “Faselhannes” and “Narro” in Bad Waldsee are also equipped with these jester’s sausages.

“White jesters” from Rottweil with jester’s sausage, photo: Helmut Reichelt

Hollow Jingling: The Jester’s Bells

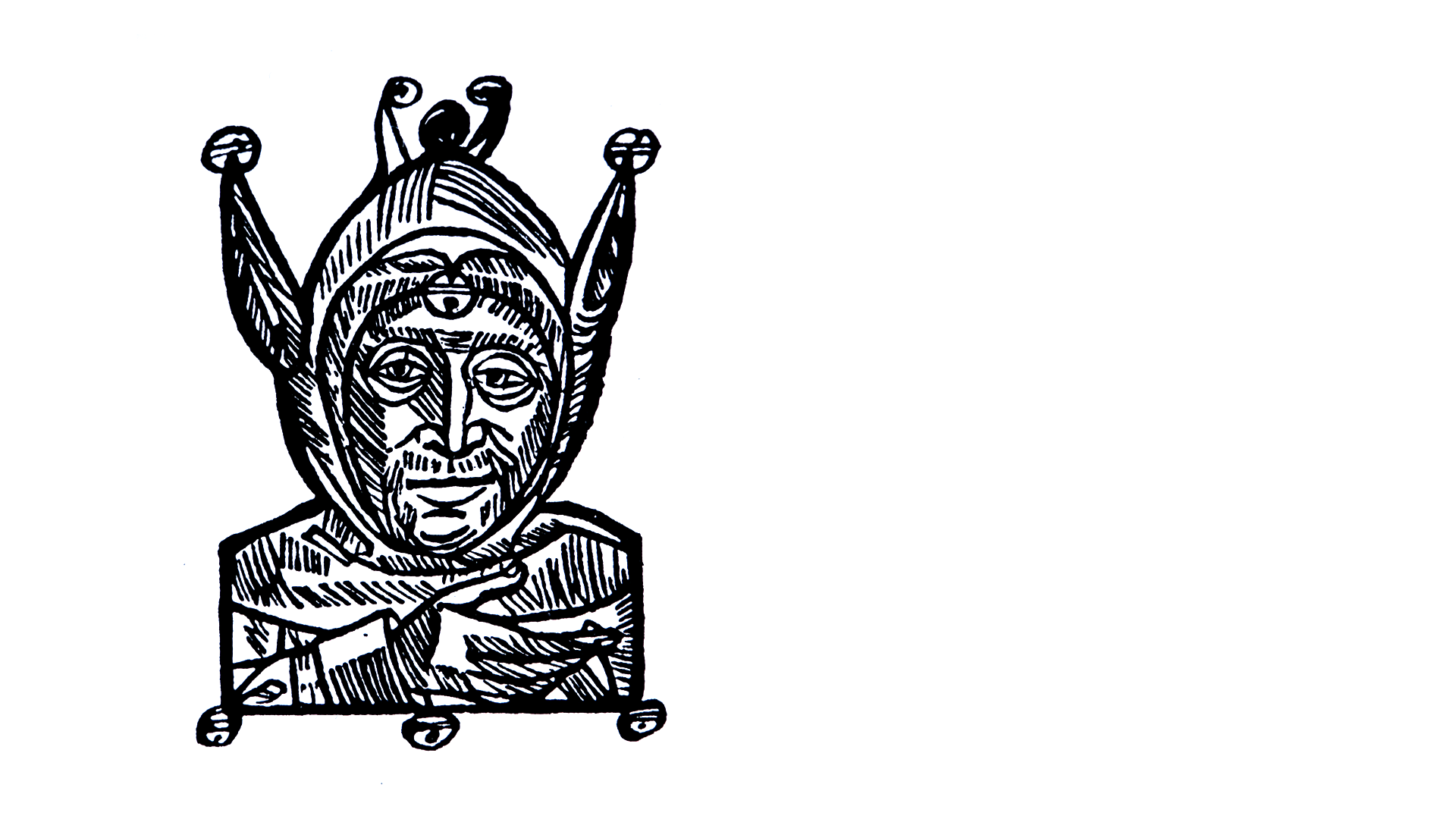

One of the most important features of the standard jesters were the bells, which were usually “rollers” (small balls with sound slits and a rolling object in the middle, creating a sound) hanging from the donkey ears of the jester’s cap, and from all of the tails of the jester’s garment. Bells appear in depictions from as early as the start of the 15th century. They signalled, first of all, the hollow jingling as well as the fact that whatever the jester uttered was meaningless. Later, however, they were also interpreted theologically and associated with what St. Paul wrote in his first letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor. 13:1), where it says: “If I spoke with the tongues of men and of angels, but had not charity (Latin: caritas), I should be sounding like brass and tinkling like a bell.” Like the marotte and the mirror, the bells also allude to the jester’s lack of charity. A woodcut vignette from a Low German edition of “Ship of Fools” from 1497 shows the multitude of bells on a single bust of a jester.

Narr mit Schellen, Holzschnitt aus: Dat Narren Schyp, Lübeck 1497, nach: Albert Schramm (Hrsg.): Der Bilderschmuck der Frühdrucke, Bd. 13, Leipzig 1929, Taf. 37, Abb. 268

Bells as Rollers

The jingling “roller” bells, which have since grown into balls up to 13 cm in diameter, are still one of the most prominent and unmistakable features of many of the masked Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht figures. For the “Villinger Narro” festivities, they are cast in bronze and weigh up to 20 kilograms when worn on straps crossed over the chest and back. In most other jester towns, the “Gschell” (set of bells) is made from scythe steel, with two hammered half-shells soldered together. The roller bells are jingled by to the jester’s special walk, which changes from place to place, and create a deafening noise when all of the jesters appear en masse.

Villinger “Narro” with “rollers”, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Bell Types

There is more than just one type of jester’s bell. During the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities it is almost only the round “roller bells” that are seen (and heard). In Tyrol, on the other hand, there are two types of bells (each with a different name). Cup-shaped bells, with a freely swinging clapper, are one type that are known as “Schellen”. Tyrol Fastnacht figures with this type of bell are therefore called “Schellers”, while the bearers of the round “roller” type are called “Rollers”. Within the Swabian Fastnacht area there is only one place where the other type of bell – featuring a clapper sticking out horizontally from a waist belt – is worn instead of the “roller” type: Wilflingen, on the southwestern Alb ridge. The “bell jesters” there seem to hark back to models from Tyrol or Trentino, which presumably reached Wilflingen in the 18th century via a noble family called de Baratti with roots in Trentino.

“Schellnarren” from Wilflingen, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de