The Jester’s Attributes 2

Donkey Ears: A Symbol of Simplicity

The image of the standard fool was associated with two long donkey ears on his cap since at least the early 15th century. The donkey – the epitome of simplicity and lack of insight in Greco-Roman tradition – characterised the fool as “insipiens”, as someone who lacks any form of wisdom (from the Latin “sapientia”). According to medieval understanding, the beginning of all wisdom was seen in the fear of God: “Timor Domini initium sapientiae”. The fact that the foolish jester lacked precisely this insight was to be indicated by his donkey ears. On the chimney frieze of the old Cologne Gürzenich from around 1440, which was sadly destroyed during the Second World War, a music-making jester can be seen being held by his donkey ears by a dancing couple, thus being mocked.

Music-making jester, held by the donkey ears by a dancing couple, detail from the fire place frieze of the old Cologne Gürzenich, circa 1440, destroyed in the Second World War, photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne, No. 17198

Donkey Ears: A Symbol of Simplicity

The image of the standard fool was associated with two long donkey ears on his cap since at least the early 15th century. The donkey – the epitome of simplicity and lack of insight in Greco-Roman tradition – characterised the fool as “insipiens”, as someone who lacks any form of wisdom (from the Latin “sapientia”). According to medieval understanding, the beginning of all wisdom was seen in the fear of God: “Timor Domini initium sapientiae”. The fact that the foolish jester lacked precisely this insight was to be indicated by his donkey ears. On the chimney frieze of the old Cologne Gürzenich from around 1440, which was sadly destroyed during the Second World War, a music-making jester can be seen being held by his donkey ears by a dancing couple, thus being mocked.

Music-making jester, held by the donkey ears by a dancing couple, detail from the fire place frieze of the old Cologne Gürzenich, circa 1440, destroyed in the Second World War, photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv, Cologne, No. 17198

The Donkey in Fastnacht Tradition

While the donkey ears have largely disappeared from the jester’s hat in the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht tradition (only the traditional gugel shape of the old jester’s cap has been preserved as a face mask), the donkey is still very much present as its own mask figure. In Villingen, the donkey has an important role as the “Butzesel”, and in Bad Waldsee, “Werner’s Donkey” is one of the big attractions of the Fasnet festivities there.

“Butzesel” in Villingen, photo: Ralf Siegele , www.ralfsiegele.de

Rooster’s head: Symbol of Desire

Along with the donkey, another animal that was associated with the fool very early on due to certain characteristics was the rooster. If the donkey was simply considered stupid and stubborn, the rooster stood for sexual desire, unbridled passion and horniness. The trait of foolish instinctiveness was visually displayed in the same prominent place as the donkey ears – on the jester’s cap. In the most elaborate form of design, the gugel was surmounted by a fully formed rooster’s head, which could repeated on the jester’s head on the marotte. For example, it is depicted in a late 15th century French psaltery used by King Charles VIII.

Jester with rooster’s head on cap and marotte, detail of a miniature from a Psalter for Charles VIII, late 15th century, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Narr mit Hahnenkopf auf Kappe und Marotte, Detail einer Miniatur aus einem Psalter für Karl VIII., spätes 15. Jh., Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Rooster’s head: Symbol of Desire

Along with the donkey, another animal that was associated with the fool very early on due to certain characteristics was the rooster. If the donkey was simply considered stupid and stubborn, the rooster stood for sexual desire, unbridled passion and horniness. The trait of foolish instinctiveness was visually displayed in the same prominent place as the donkey ears – on the jester’s cap. In the most elaborate form of design, the gugel was surmounted by a fully formed rooster’s head, which could repeated on the jester’s head on the marotte. For example, it is depicted in a late 15th century French psaltery used by King Charles VIII.

Jester with rooster’s head on cap and marotte, detail of a miniature from a Psalter for Charles VIII, late 15th century, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Narr mit Hahnenkopf auf Kappe und Marotte, Detail einer Miniatur aus einem Psalter für Karl VIII., spätes 15. Jh., Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, lat. 774, fol. 63 v.

Cockscomb: Insinuated Voluptuousness

In the simpler version, as an engraving by Lucas van Leyden from 1520 shows, instead of a full rooster’s head on the jester’s cap, only a jagged strip of cloth running from front to back was attached, so as to resemble a rooster’s crest. This seemed to be enough to characterise the wearer accordingly. In the copperplate engraving by Lucas von Leyden, the aging old jester displays his unbridled behaviour by approaching a young girl and kissing her on the cheek. The purse on the belt of the horny old man indicates that this is about love for sale, and the two disparate faces speak volumes.

Jester with a cockscomb cap and a young woman, copper engraving by Lucas van Leyden, Netherlands 1520, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-P-OB 1738

Rooster’s Head complete with Cockscomb

In the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, the rooster’s head and the cockscomb on the jester’s cap were sometimes even combined. This is how an anonymous Dutch copperplate engraving from the first quarter of the 17th century illustrates it. The jester’s cap, with his cat on the shoulder, is surmounted by an elegantly curved rooster’s head, which is also visually emphasised by a luxuriant comb.

Jester with cockscomb cap and a young woman, detail from an anonymous Dutch copper engraving: Woman with mirror and fool, 1st quarter of the 17th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-P-OB 77.716

Rooster’s Head complete with Cockscomb

In the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque, the rooster’s head and the cockscomb on the jester’s cap were sometimes even combined. This is how an anonymous Dutch copperplate engraving from the first quarter of the 17th century illustrates it. The jester’s cap, with his cat on the shoulder, is surmounted by an elegantly curved rooster’s head, which is also visually emphasised by a luxuriant comb.

Jester with cockscomb cap and a young woman, detail from an anonymous Dutch copper engraving: Woman with mirror and fool, 1st quarter of the 17th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-P-OB 77.716

Donkey ears and horny feathers

The simplest way of combining the rooster motif with the jester’s costume was to attach one or more real rooster feathers to the donkey-eared cap. The fact that this was done, and that it was perhaps even particularly popular in practice thanks to the low cost, is amply demonstrated by relevant visual documentation. This is clearly visible, for example, on a jester’s gugel which Hans Sebald Behm depicted in an engraving in the first half of the 16th century.

Female jester with donkey-eared cap and rooster’s feathers, detail from a copper engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham: “Narr und Närrin”, Nuremberg, 1st half of the 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-B-OB 10.929

Donkey ears and horny feathers

The simplest way of combining the rooster motif with the jester’s costume was to attach one or more real rooster feathers to the donkey-eared cap. The fact that this was done, and that it was perhaps even particularly popular in practice thanks to the low cost, is amply demonstrated by relevant visual documentation. This is clearly visible, for example, on a jester’s gugel which Hans Sebald Behm depicted in an engraving in the first half of the 16th century.

Female jester with donkey-eared cap and rooster’s feathers, detail from a copper engraving by Hans-Sebald Beham: “Narr und Närrin”, Nuremberg, 1st half of the 16th century, Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinett, Inv. No. RP-B-OB 10.929

Rottweiler “Biss” with “Boschen” made from rooster’s feathers, photo: Ralf Siegel www.ralfsiegele.de

Rooster Feathers in Fastnacht Tradition

Given the intensity with which the rooster motif was present in the visual tradition, it would be surprising if it had not been continued in the Fastnacht tradition. As would be expected, it is still clearly present on a number of traditional Fastnacht elements. The closest thing to the late medieval models is probably the Rottweiler “Biss”. For this type of white jester, the donkey ears have disappeared from the gugel headpiece, but in exactly the same place where the rooster’s head or comb used to be, it still bears the “Wischer” (“wiper”) with a tuft of rooster feathers.

Rottweiler “Biss” with “Boschen” made from rooster’s feathers, photo: Ralf Siegel www.ralfsiegele.de

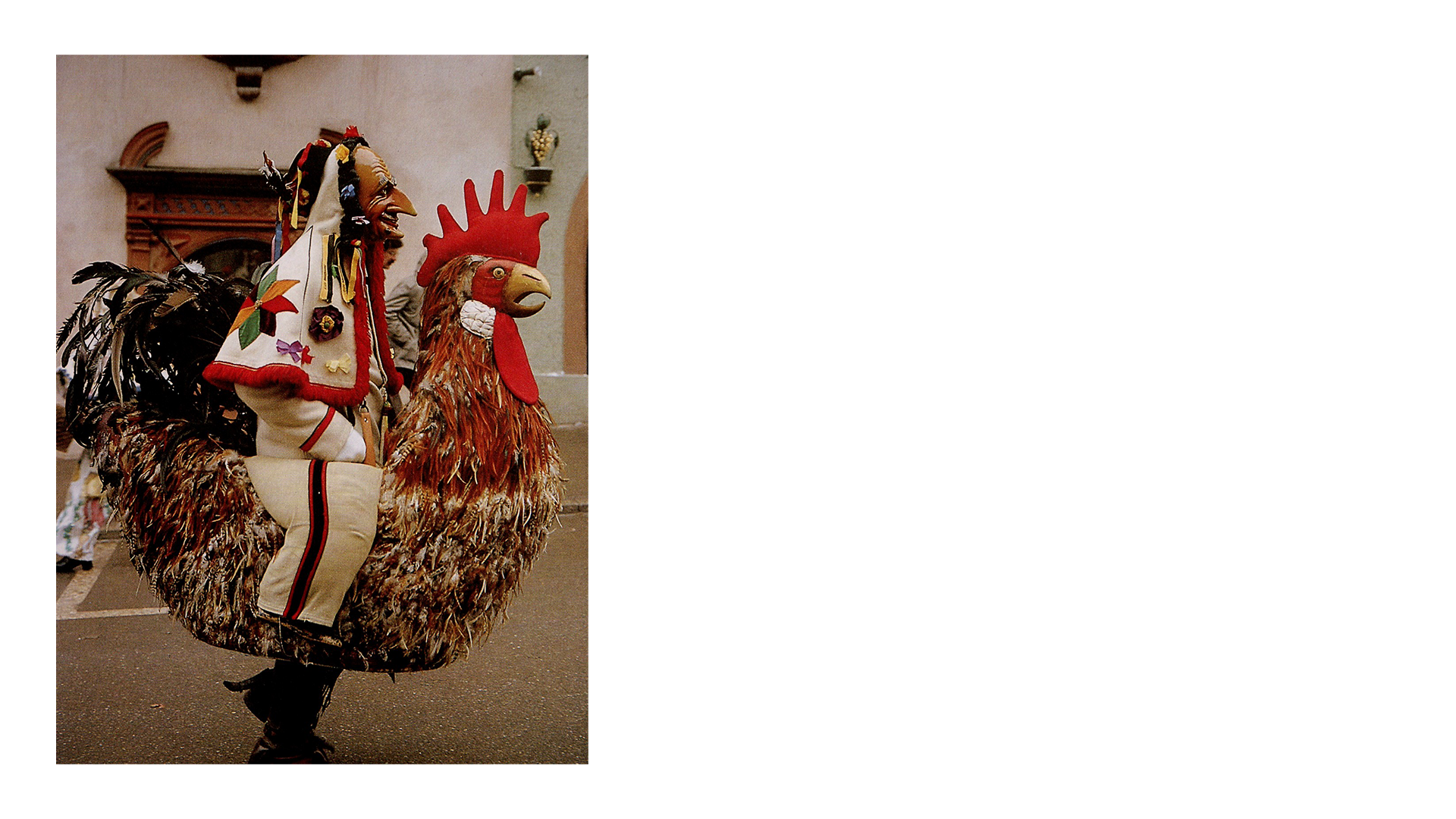

The Fastnacht Rooster Rider

Like the donkey, the rooster also appears as a solo figure during various Fastnacht festivities. The most popular example is a human-sized mounted rooster which is actually carried by the person riding it. In late medieval and baroque symbolism, the image of the rooster rider was often associated with the “cuckold” – the cuckolded husband or deceived spouse. Once again, the rooster revolves around the same theme: sexuality. Picturesque examples of the rooster rider can be found during Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, for example in the Rottweiler “Guller” (meaning “Rooster”) or the “Gullerreiter” (meaning “Rooster Rider”) from Wolfach in the Kinzigtal.

Rottweiler “Guller”, photo: Helmut Reichelt

The Foxtail: A Dubious Symbol

Another animal symbol closely associated with the jester was the foxtail, which was either sewn onto the smock or hood of the jester’s costume or which the jester carried hanging from a staff, like a sceptre. In the first variant, the foxtail is found several times in paintings by Pieter Bruegel. In the second variant as a staff crown it appears, for example, on a 17th century playing card, where the jester is supposed to embody the “Vice-Re”. In its symbolism, the foxtail in the late Middle Ages did not stand for intelligence and shrewdness, as one might assume today. Instead, it stood for cunning and dishonesty. Calling someone a “foxtail” was anything but a compliment.

Jester with foxtail sceptre, playing card, 17th century, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, Sp. 3508, 517

Jesters with Foxtails

During Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, the foxtail is a common attribute, usually attached to the headpiece of the white jesters, either individually or in bundles of up to three, depending on the specific Fastnacht figure. For the “Fuchswadel” jesters in Fridingen an der Donau, the foxtail is particularly striking. Here, it is worn to the side of the face mask. The prevalence of the foxtail here refers not least to the town’s Fastnacht nickname. For the duration of the Fastnacht festivities, the whole of Fridingen is known as “Fuchsau” (“the fox’s den”).

Fridinger jesters with foxtails, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Jesters with Foxtails

During Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht festivities, the foxtail is a common attribute, usually attached to the headpiece of the white jesters, either individually or in bundles of up to three, depending on the specific Fastnacht figure. For the “Fuchswadel” jesters in Fridingen an der Donau, the foxtail is particularly striking. Here, it is worn to the side of the face mask. The prevalence of the foxtail here refers not least to the town’s Fastnacht nickname. For the duration of the Fastnacht festivities, the whole of Fridingen is known as “Fuchsau” (“the fox’s den”).

Fridinger jesters with foxtails, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

A Bladder: Reflection of the World of Foolishness

In the visual arts, another symbol of foolishness whose message lay, paradoxically, in its own lack of content was the bladder. Its symbolism is perhaps most clearly revealed in a coloured anonymous copperplate engraving from the end of the 16th century, which shows the whole world as a jester’s head. The most interesting aspect here is the marotte, which is supposed to resemble the mapped globe stuck under a huge donkey-eared cap: It consists of a large soap bubble floating above a bubble tube, which presumably only lasts a few moments and bears the Bible inscription inside: “Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas” (“Everything is vain and void”). The image of the world of foolishness – prone to bursting at any time and dissolving into nothing – is more relevant today than ever.

The world as a fool’s head, coloured copper engraving, late 16th century, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Kupferstichkabinett, La 213

The Pig’s Bladder: Attribute of the Jester

A more or less direct line leads us from the image of the soap bubble to the pig’s bladder in the jester’s hand. One of the first depictions of a jester in a donkey-eared costume with a stick and an attached “Saubloder” (the Alemannic term for “big’s bladder” and the prop in question) can be found as a relief on the column of the Pfeiferbrunnen in Bern, created around 1540 by Hans Gieng. The little jester, playing with the inflated bladder and using it like a balloon, is part of a circle of dancing child jesters

Little jester with pig bladder, stone relief on the fountain column of the Pfeiferbrunnen by Hans Gieng in Bern, between 1544 and 1546, photo: Werner Mezger

Pig Bladders during Fastnacht

To this day, the pig’s bladder is a commonly found teasing instrument of Fastnacht jesters. It can be seen used in large numbers, for example, by the “Schuttig” in Elzach. The use of “Saublodere” as part of traditional Fastnacht customs had a double purpose: On a very practical level, butchers had more pig bladders due to the large number of pigs being slaughtered before the beginning of Lent. And, on a symbolic level, the inflated “Saublodere” were a striking symbol of the futility and hollowness of all the foolish Fastnacht activities themselves. Strictly speaking, the pig’s bladder in the jester’s hand is also even the image of its bearer – in a similar way to the marotte being decorated with the jester’s own face. The Latin root “fol” for “fool”, as found in the French “fou” or the English “fool”, derives from the Latin “follis” and means “empty bag” or “bag without contents”. It was precisely this inner hollowness that was considered by theologians and moral satirists to be the decisive characteristic of the jester.

Elzacher “Schuddig” with “Saublodere”, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Pig Bladders during Fastnacht

To this day, the pig’s bladder is a commonly found teasing instrument of Fastnacht jesters. It can be seen used in large numbers, for example, by the “Schuttig” in Elzach. The use of “Saublodere” as part of traditional Fastnacht customs had a double purpose: On a very practical level, butchers had more pig bladders due to the large number of pigs being slaughtered before the beginning of Lent. And, on a symbolic level, the inflated “Saublodere” were a striking symbol of the futility and hollowness of all the foolish Fastnacht activities themselves. Strictly speaking, the pig’s bladder in the jester’s hand is also even the image of its bearer – in a similar way to the marotte being decorated with the jester’s own face. The Latin root “fol” for “fool”, as found in the French “fou” or the English “fool”, derives from the Latin “follis” and means “empty bag” or “bag without contents”. It was precisely this inner hollowness that was considered by theologians and moral satirists to be the decisive characteristic of the jester.

Elzacher “Schuddig” with “Saublodere”, photo: Ralf Siegele, www.ralfsiegele.de

Mark on the Forehead as a Symbol of Foolishness

A symbol of the jester that was only occasionally depicted in the visual arts (but all the more drastically emphasised when it was) was a festering bump on the forehead of the “insipiens” that was hard to overlook: the jester’s mark. It can be clearly seen in a painting by Quinten Metsys from around 1510, entitled “Allegory of Foolishness”. With a mysterious gesture of silence and bearing real donkey ears, the hook-nosed personification of foolishness shows itself to the viewer in profile, while the rooster’s head on its cap crows out into the world and a little jester crawls out of the marotte, showing his bare bottom. The unaesthetic eye-catcher on the forehead of the strange central figure, however, is precisely the ugly ulcer that was understood, to a certain extent, as being the symbol of foolishness. Incidentally, a separate type of image known as the “jester’s cut” showed the futility of attempting to surgically remove the jester’s mark.

Allegory of Foolishness, painting by Quinten Metsys, circa 1510, Worcester, Worcester Art Museum, formerly: Prof. Dr. Julius S. Held Collection

Fastnacht Mask featuring the Jester’s Mark

The mark of foolishness on the forehead can also be found on historical Fastnacht masks, for example on one from Rottweil from the late 18th century that is no longer worn today. The fact that this is not a coincidence, but rather a deliberately emphasised physiognomic feature by the carver, is recognisable at first glance. Museum collections of masks, for example in the Rietberg Museum in Zurich, contain historical face masks on which the jester’s mark is affixed in exactly the same place. It seems, therefore, to have corresponded to a previously widespread idea.

Fastnacht mask with a jester’s mark on the forehead, Rottweil, 18th century, private collection, photo: Werner Mezger

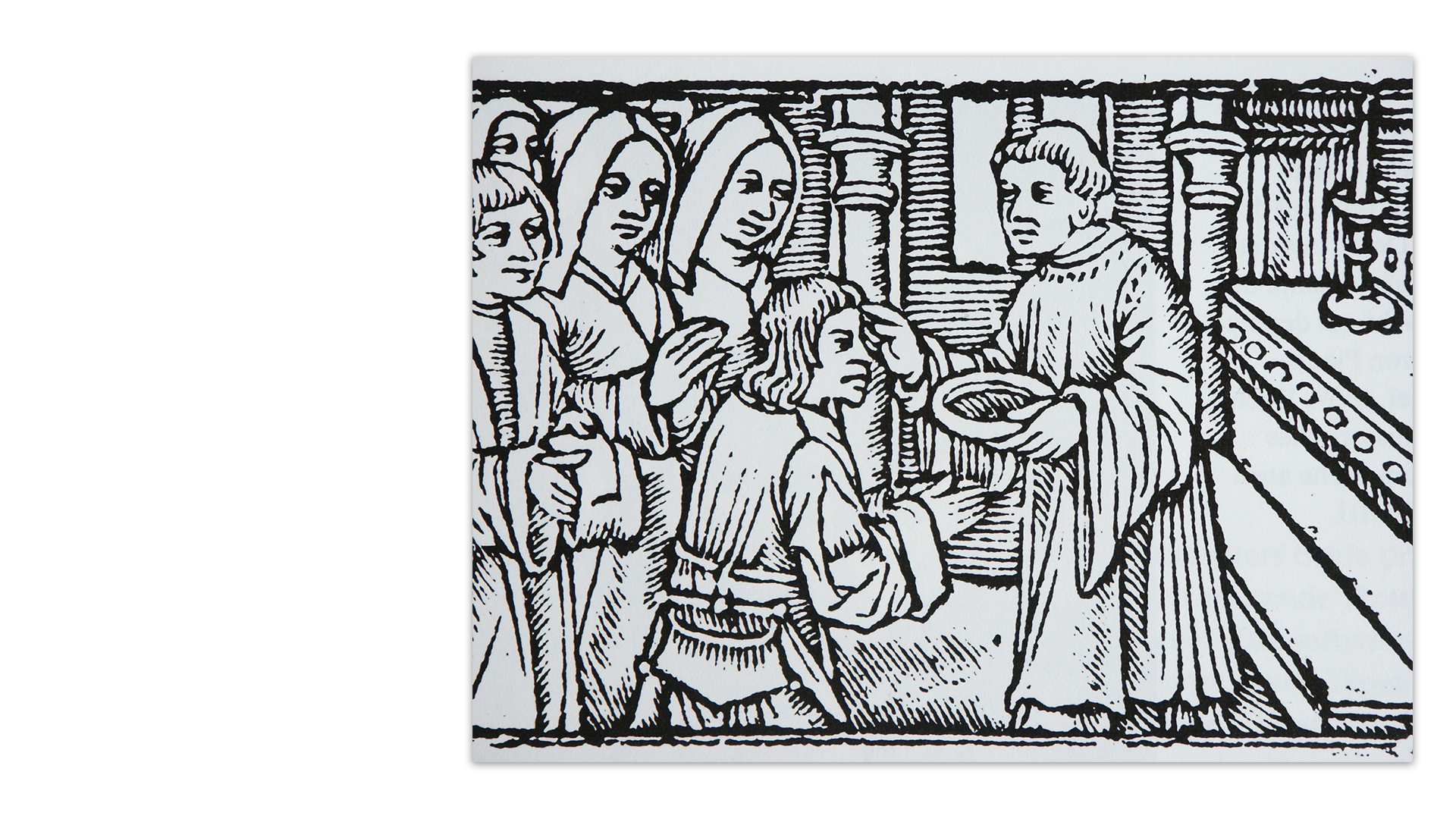

Sign of the Cross instead of the Jester’s Mark

The deeper meaning of the jester’s mark only becomes clear when we look at the religious penitential rite of Ash Wednesday. The mark, as can easily be seen in a simple woodcut depiction of the donation of ashes from the early 16th century, is located on the exact same spot on the forehead that is marked with the ash cross by the priest on the first day of Lent. This context also explains the wording of Sebastian Brant’s criticism of any Fastnacht jesters who do not stop their festivities in time and continue celebrating into Ash Wednesday. Brant reproaches them: “They do not want to have the sign of God / they refuse to resurrect with Christ”. Exchanging the jester’s mark for the ash cross and visibly repenting – that, then, was what was expected of Fastnacht revellers as they entered Lent.

Marking with the cross of ash, border of a calendar of the month of March in a French book of hours, printed on parchment by Simon Vostre, Paris, circa 1510, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Im. mort. 37

Sign of the Cross instead of the Jester’s Mark

The deeper meaning of the jester’s mark only becomes clear when we look at the religious penitential rite of Ash Wednesday. The mark, as can easily be seen in a simple woodcut depiction of the donation of ashes from the early 16th century, is located on the exact same spot on the forehead that is marked with the ash cross by the priest on the first day of Lent. This context also explains the wording of Sebastian Brant’s criticism of any Fastnacht jesters who do not stop their festivities in time and continue celebrating into Ash Wednesday. Brant reproaches them: “They do not want to have the sign of God / they refuse to resurrect with Christ”. Exchanging the jester’s mark for the ash cross and visibly repenting – that, then, was what was expected of Fastnacht revellers as they entered Lent.

Marking with the cross of ash, border of a calendar of the month of March in a French book of hours, printed on parchment by Simon Vostre, Paris, circa 1510, Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Im. mort. 37