Festivities and Lent

Meat Consumption and Gluttony

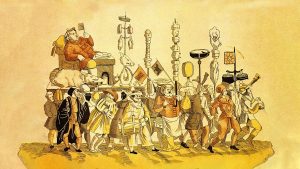

During Fastnacht – originally the last “night before fasting” – all foods that were forbidden after Ash Wednesday could be eaten one last time. During Lent, all meat from warm-blooded animals and everything associated with them was taboo. So, this also included lard, fat, butter, milk, cheese and eggs. A coloured Italian woodcut from the 16th century shows how people feasted for the last time before this major break in the economic year (initially only on Shrove Tuesday, but later on also on the days leading up to it): Fastnacht, or Karneval, is personified as an obese man surrounded by sumptuous meat products and even flanked by a pig, and is carried on a sedan chair. His companions have formed a grotesque triumphal procession with similar meat-tipped skewers. What they demonstrate is the “vivere secundum carnem” – the “living by the flesh”.

Il triomfo del carneval, coloured woodcut, Venice 16th century, Kitzingen, Deutsches Fastnachtsmuseum

Meat Consumption and Gluttony

During Fastnacht – originally the last “night before fasting” – all foods that were forbidden after Ash Wednesday could be eaten one last time. During Lent, all meat from warm-blooded animals and everything associated with them was taboo. So, this also included lard, fat, butter, milk, cheese and eggs. A coloured Italian woodcut from the 16th century shows how people feasted for the last time before this major break in the economic year (initially only on Shrove Tuesday, but later on also on the days leading up to it): Fastnacht, or Karneval, is personified as an obese man surrounded by sumptuous meat products and even flanked by a pig, and is carried on a sedan chair. His companions have formed a grotesque triumphal procession with similar meat-tipped skewers. What they demonstrate is the “vivere secundum carnem” – the “living by the flesh”.

Il triomfo del carneval, coloured woodcut, Venice 16th century, Kitzingen, Deutsches Fastnachtsmuseum

Carnal Desire and Fornication

Being allowed to live “by the flesh” during Fastnacht one last time did not only refer to the consumption of meat, but equally to “flesh” in a figurative sense – that is, to sexual activities. During Lent, any form of sexual behaviour was also forbidden. That is why people behaved in sexually promiscuous ways again before Ash Wednesday. As the main Fastnacht protagonists, the jesters were said to be particularly untamed in their lust and desire anyway, which is why they are repeatedly shown in seductive contexts in the visual arts. A copperplate engraving by Hans Sebald Beham from 1541 shows a half-dressed jester in a donkey-eared costume being dragged into a bathtub by two naked girls. So, this kind of reference to the “flesh” was also an integral part of Fastnacht.

Hans Sebald Beham: Two women bathing undress a fool, copper engraving 1541, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

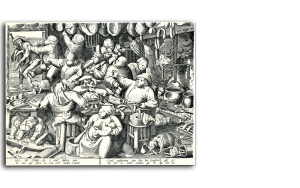

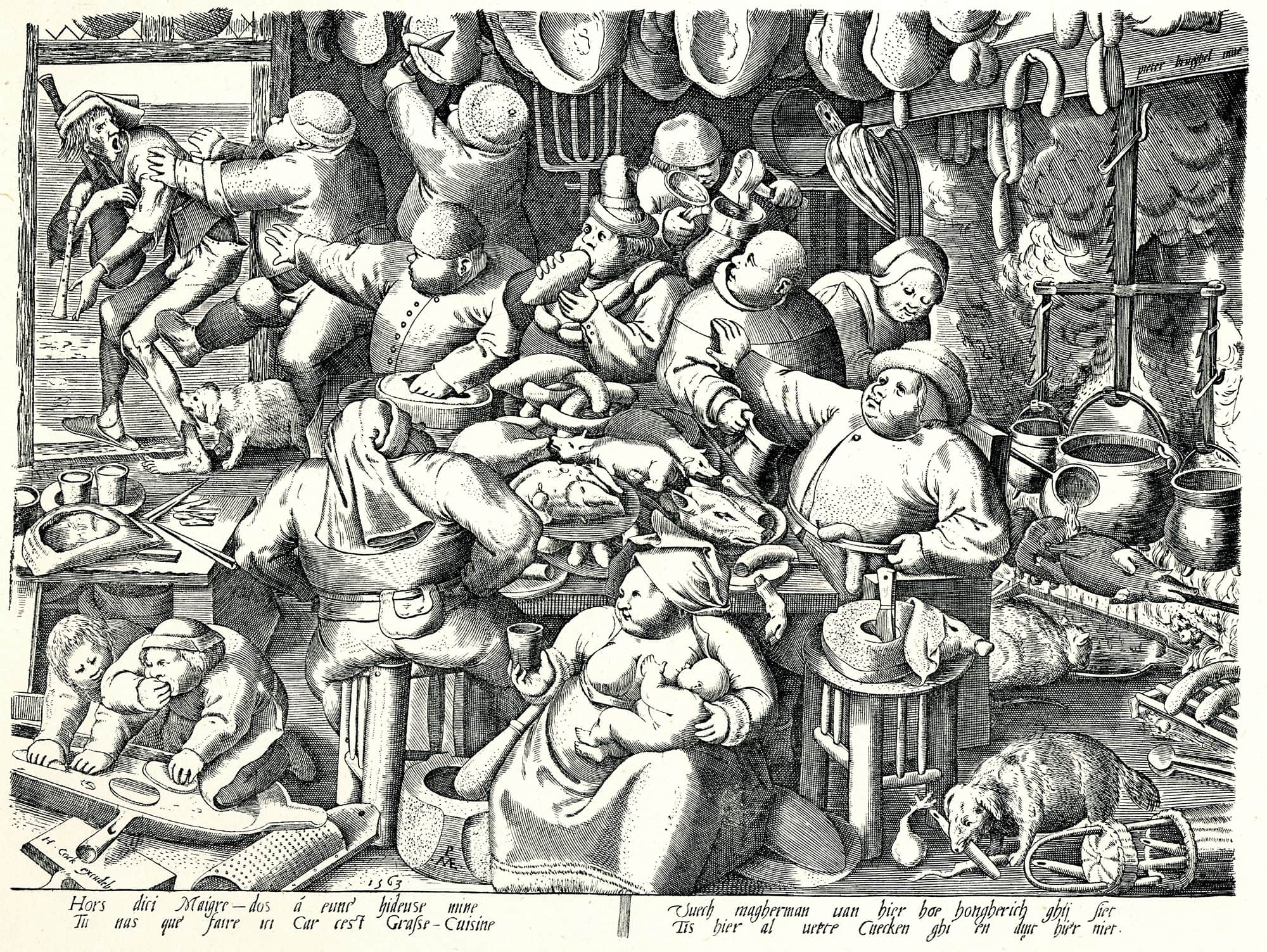

‘Fat Kitchen’ before Lent

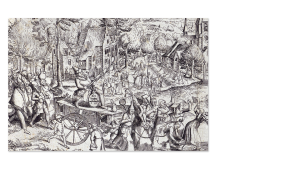

However, the artists of the early modern period were more interested in the concrete use of meat as food than in the subtle contrast between carnal desire and sexual abstinence: The contrast between consumption and renunciation, between gluttony and hunger, was thematised in a wide variety of ways. Around 1540, Pieter Breugel the Elder created the patterns for a pair of copperplate engravings showing “fat kitchen” and “lean kitchen”, referring less to the social divide between wealth and poverty than to the contrast between Fastnacht and Lent dictated by the Christian year. The “fat kitchen” sheet features consistently well-fed figures feasting on an array of sumptuous meats as they toss the thin figure, representative of Lent, out the door.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The fat kitchen”, copper engraving circa 1540, from René van Basetlaer: “Les éstampes de Peter Bruegel l’ancien”, Bruxelles 1908, No. 159

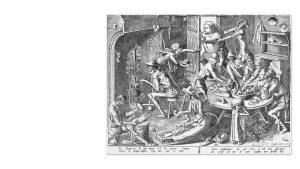

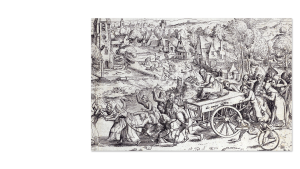

‘Lean Kitchen’ after Fastnacht

The “lean kitchen” sheet shows, in a similar arrangement to that of the “fat kitchen”, people emaciated to the bone feeding on a meagre supply of typical fasting food. Mussels and fish are dominant here, and onions and radishes are also occasionally seen. A woman who cannot breastfeed her child pours it a drink, a man prepares some fish, another cooks a vegetable soup. In analogy to the image of the “fat kitchen”, which shows the ejection of the representative of Lent in the background, here, the fat representative of Fastnacht is driven out of the room and dragged out the open door.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: “The lean kitchen”, copper engraving circa 1540, from René van Basetlaer: “Les éstampes de Peter Bruegel l’ancien”, Bruxelles 1908, No. 159

Literary Roots of the Two-Kitchen Motif

Conflicting pairs of images like those of the “fat” and “lean” kitchen, which were often used from the 16th century onwards to thematise the contrast of eating habits before and after Ash Wednesday, were the visual implementation of a motif that was already much older in literature. As early as the first half of the 14th century, there were the “Contrasti”, controversial debates that depicted the conflict between Fastnacht and Lenten foods. The earliest known allegorical poetry of this kind can be found in the Libro de Buen Amor by the Spanish theologian and poet Juan Ruiz, dated 1330/40. This is the title page of a manuscript of the Libro de Buen Amor written shortly after the author’s death, which refers to the Fastnacht/Lent dialogue, written in rhyme.

Manuscript of the “Libro de Buen Amor” by Juan Ruiz, circa 1330/40, table of contents (subsequently added) with reference to the dialogue between Lent and Fastnacht, Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional España

Theological Origin in the Two Realms Doctrine

The contrasting view of Fastnacht and Lent, however, reached back much further. It was based on the thinking of St. Augustine, who developed the model for a clear distinction between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of the devil in his main work “On the State of God” at the end of antiquity, which from that point on had an enormous influence on theology. Based on this concept of interpretation, late medieval preachers increasingly interpreted the relationship between Fastnacht and Lent in accordance with Augustine’s doctrine of the two kingdoms: They equated Fastnacht – where, in their view, the devil was literally on the loose – with the “civitas diaboli” (the State of the Devil), and the holy nature of Lent with the “citivas Dei” (the State of God). The woodcut title of an edition of Augustine printed in Basel in 1498 shows in the upper field the Doctor of the Church at his desk.

Saint Augustine at his writing desk, and below the two warring states of Jerusalem and Babylon, coloured woodcut from Aurelius Augustinus’ “De civitate Dei”, Basel 1489, Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, Aleph H III 32:1, p. 18

Augustine as a Model of Interpretation

The lower field of the same woodcut visualises the core idea of Augustine’s main work – the confrontation of the State of God with the State of the Devil. This is symbolised by the two opposing cities of Jerusalem (left) and Babylon (right) – populated by angels in the former and by devils in the latter – and so are at odds with each other. Representations such as these, in conjunction with Augustinian-influenced sermons of the pre-Lent and Lent periods, were ultimately also the starting point for a type of visualisation of the contrast between Fastnacht and Lent, which clothed the trial of strength of the two periods in the image of an armed conflict. Similar to the battle between the fundamentally different cities of Jerusalem and Babylon, in this traditional motif Fastnacht and Lent are fighting against each other in a fierce battle.

The warring states of Jerusalem and Babylon, lower part from a coloured woodcut from Aurelius Augustinus’ “De civitate Dei”, Basel 1489, Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, Aleph H III 32: 1, p. 18th

Fastnacht and Lent at Odds

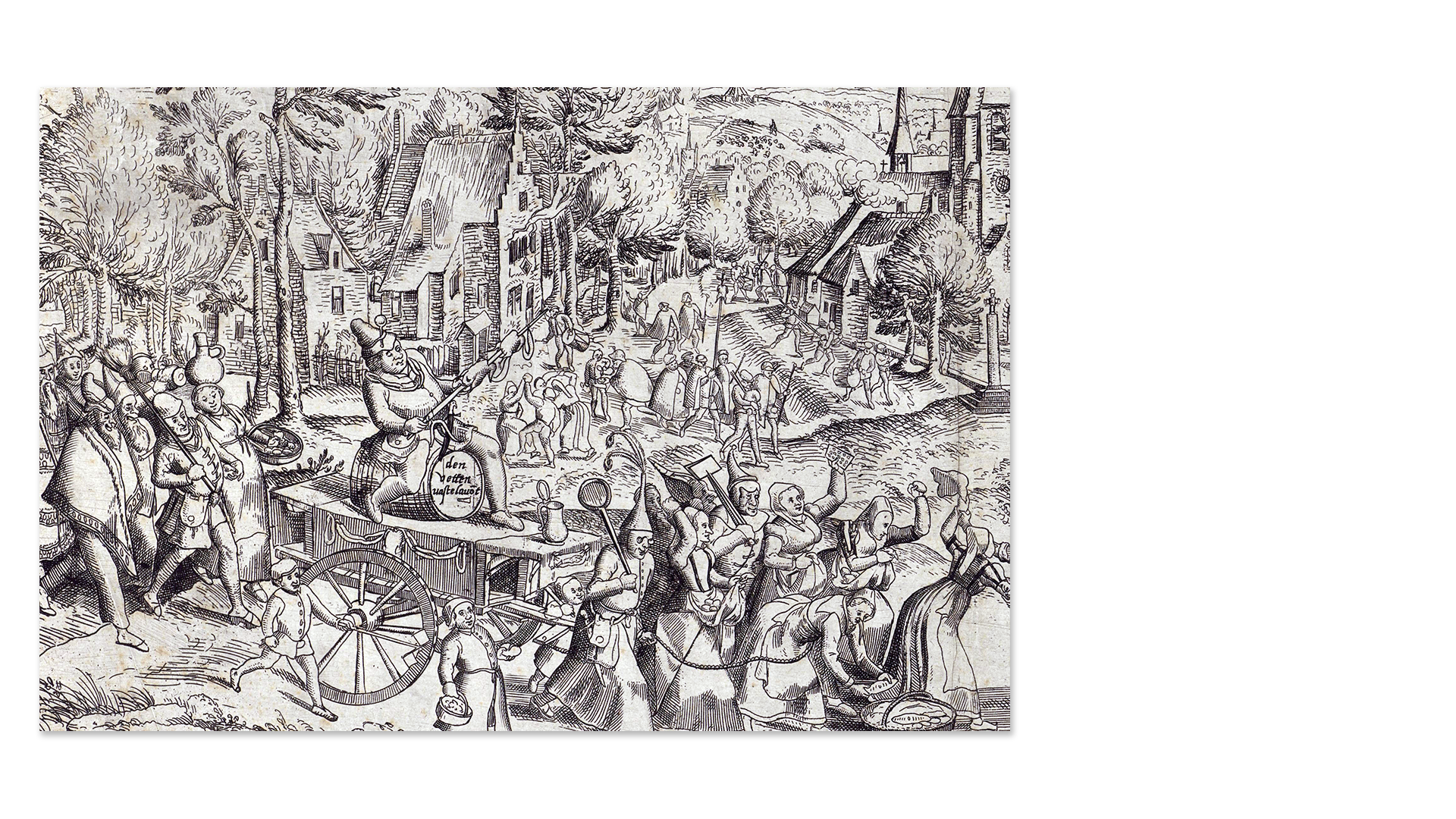

Arather complex example of the image type of the battle between Fastnacht and Lent is an engraving published by Hieronymus Cock in 1558, which is based on a drawing by Frans Hogenberg: In front of a small village church, which marks the centre of the picture, the fat representative of Fastnacht and the lean woman of Lent – each accompanied by an entourage – march on each other from the left and from the right.

The conflict between Fastnacht and Lent, copper engraving by Hieronymus Cock based on a drawing from Frans Hogenberg 1558, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

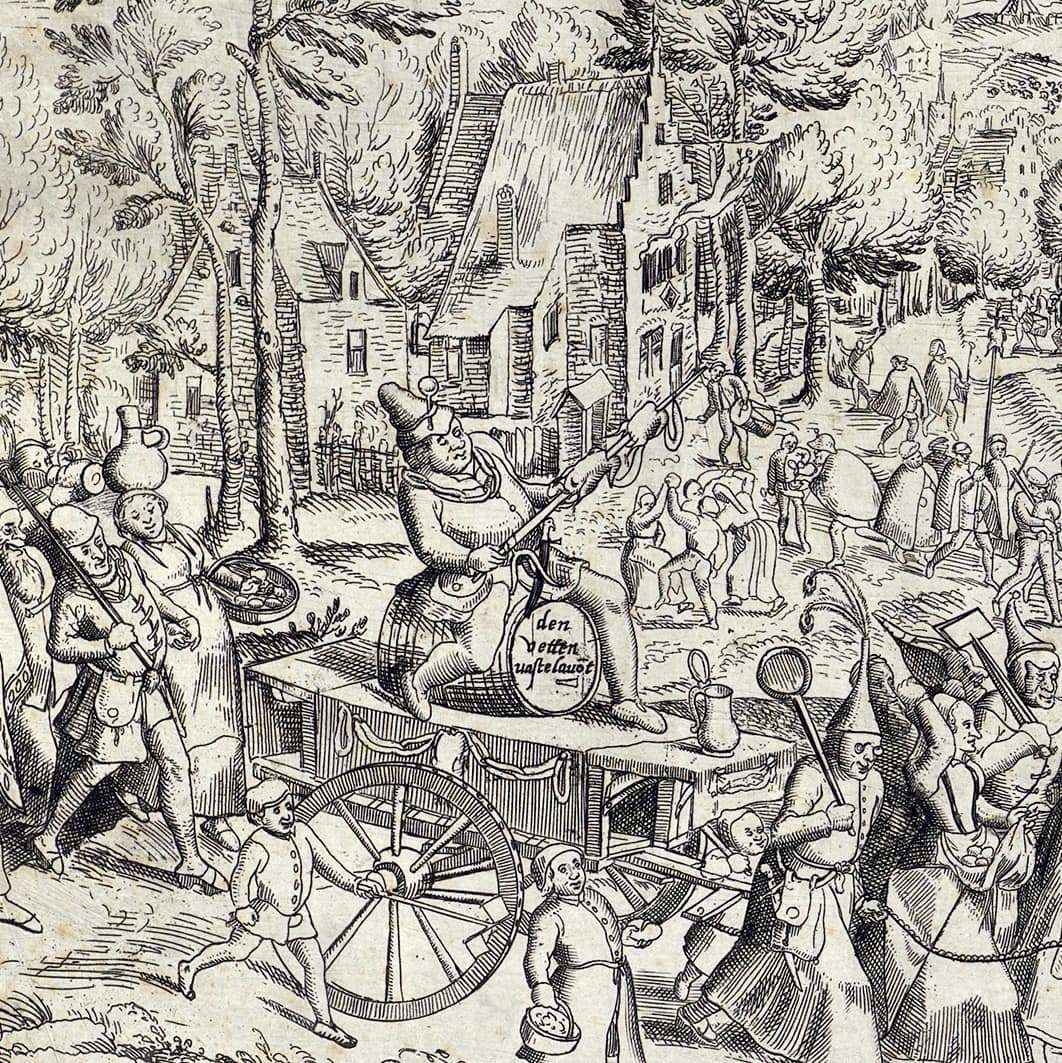

The Fat Man: Fastnacht

The “vette vastelavont” (“fat Fastnacht”) rides on a barrel mounted on a two-wheeled cart crowned with sausages. He has attached a spoon to his pointed hat, sausages also serve as his necklace, and plucked chickens and other meat products are stuck on his roasting spit, which he holds like a weapon. The warriors in front of and behind his vehicle are equipped with additional Fastnacht dishes and the necessary cooking and baking utensils: Eggs are carried in aprons, fat-baked waffles are held aloft together with a waffle iron and wine jugs are balanced on heads. The opposing party has already thrown a few fish in the path of the representatives of Fastnacht, some of whom are even partially masked.

The conflict between Fastnacht and Lent, copper engraving by Hieronymus Cock based on a drawing from Frans Hogenberg 1558, details to the bottom left, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

The Fat Man: Fastnacht

The “vette vastelavont” (“fat Fastnacht”) rides on a barrel mounted on a two-wheeled cart crowned with sausages. He has attached a spoon to his pointed hat, sausages also serve as his necklace, and plucked chickens and other meat products are stuck on his roasting spit, which he holds like a weapon. The warriors in front of and behind his vehicle are equipped with additional Fastnacht dishes and the necessary cooking and baking utensils: Eggs are carried in aprons, fat-baked waffles are held aloft together with a waffle iron and wine jugs are balanced on heads. The opposing party has already thrown a few fish in the path of the representatives of Fastnacht, some of whom are even partially masked.

The conflict between Fastnacht and Lent, copper engraving by Hieronymus Cock based on a drawing from Frans Hogenberg 1558, details to the bottom left, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

The Lean Woman: Lent

The cart on which “die mager vasten” (“lean Lent”) squats as she carries a grill with three fish in her hand is surrounded by companions carrying typical food of the fasting period: Fish in different varieties, round Lenten flatbreads and greens. They are not irritated by eggs being hurled at them from the other side. Lent required not only abstaining from meat, but also from all related animal products including fat, lard, butter, milk, cheese and eggs. As a result, at the end of Lent there was always an accumulation of unused eggs, which gave the egg a special place in food customs at Easter.

The conflict between Fastnacht and Lent, copper engraving by Hieronymus Cock based on a drawing from Frans Hogenberg 1558, details to the bottom right, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

The Lean Woman: Lent

The cart on which “die mager vasten” (“lean Lent”) squats as she carries a grill with three fish in her hand is surrounded by companions carrying typical food of the fasting period: Fish in different varieties, round Lenten flatbreads and greens. They are not irritated by eggs being hurled at them from the other side. Lent required not only abstaining from meat, but also from all related animal products including fat, lard, butter, milk, cheese and eggs. As a result, at the end of Lent there was always an accumulation of unused eggs, which gave the egg a special place in food customs at Easter.

The conflict between Fastnacht and Lent, copper engraving by Hieronymus Cock based on a drawing from Frans Hogenberg 1558, details to the bottom right, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, graphic arts collection

Pieter Bruegel’s Battle between Fastnacht and Lent

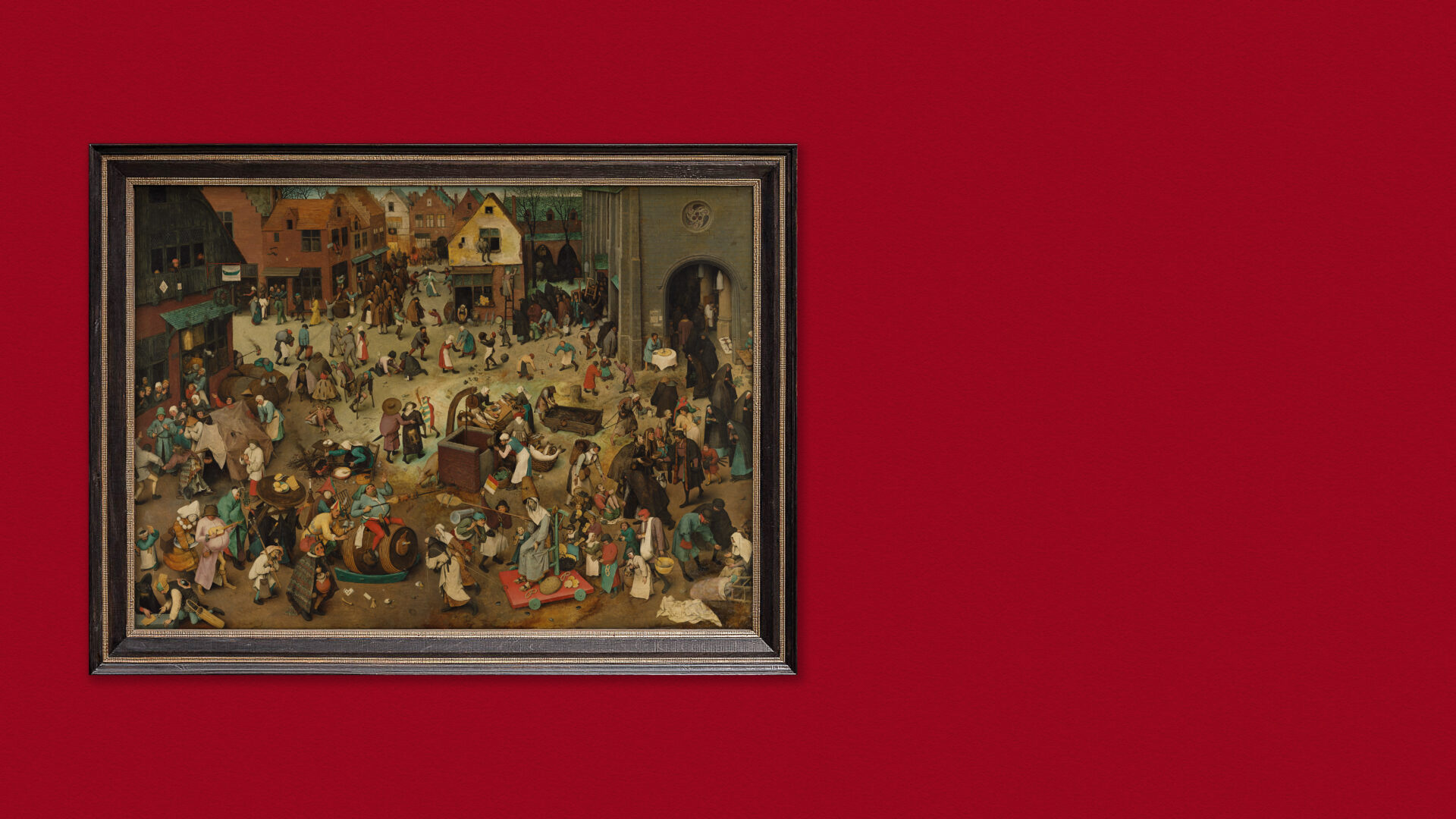

By far the most impressive and sophisticated depiction of the battle between Fastnacht and Lent was created in 1559 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in a painting that now hangs in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The wooden panel is 118 cm high and 164 cm wide. In a large square, closed off to the rear by various buildings, it shows a colourful scene with nearly 200 figures filling almost every free space on the painting’s surface.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Battle between Fastnacht and Lent, 1559, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. No. 1016

Pieter Bruegel’s Battle between Fastnacht and Lent

By far the most impressive and sophisticated depiction of the battle between Fastnacht and Lent was created in 1559 by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in a painting that now hangs in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The wooden panel is 118 cm high and 164 cm wide. In a large square, closed off to the rear by various buildings, it shows a colourful scene with nearly 200 figures filling almost every free space on the painting’s surface.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Battle between Fastnacht and Lent, 1559, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. No. 1016

Welcome to Pieter Bruegel – An Invitation

With his major painting from 1559, Pieter Bruegel produced the most inspired piece ever created in art on the relationship between Fastnacht and Lent. The painting is a universe that you can get lost in. If you want to go on an exciting voyage of discovery through Bruegel’s grandiose pictorial composition as has never been possible before, take a good quarter of an hour and enter the world of Pieter Bruegel. You will be able to walk through the masterpiece in all its details, have its subtle meanings and hidden messages explained to you and, thanks to high-resolution photographs, discover things that cannot be seen with the naked eye even when looking at the original in Vienna. Just click on “Experience now”, and off you go.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder: Battle between Fastnacht and Lent, 1559, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Inv. No. 1016, panel painting with frame