Organisation of Fastnacht

Fixed Practice between Direction and Momentum

Social historians liked to interpret the Fastnacht of the early modern period as a “demonstration of resistance”, as a rebellion against existing orders, and even as a kind of temporary revolution. That is not exactly the case. In the exuberance of the festivities, there were probably violations of norms or the unleashing of potential conflicts, and in the small French town of Romans in the Dauphiné region, Karneval actually led to a bloody revolt in 1580. But that sort of thing was the exception. Urban Fastnacht festivities usually took place in a completely different way. Although everyday rules were temporarily suspended, they were not replaced by a state of chaotic anarchy. New rules came into effect. Fastnacht customs with a high representational value for a city’s society, such as the Nuremberg “Schembartlauf”, were perfectly organised productions in which every participant had a clearly defined role. Pictures of the main Schembart event (the storming of “Hell”, which was a ship on wheels in 1539) confirm this.

Storming of “Schembart Hell” in Nuremberg in 1539, depiction in a Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

Fixed Practice between Direction and Momentum

Social historians liked to interpret the Fastnacht of the early modern period as a “demonstration of resistance”, as a rebellion against existing orders, and even as a kind of temporary revolution. That is not exactly the case. In the exuberance of the festivities, there were probably violations of norms or the unleashing of potential conflicts, and in the small French town of Romans in the Dauphiné region, Karneval actually led to a bloody revolt in 1580. But that sort of thing was the exception. Urban Fastnacht festivities usually took place in a completely different way. Although everyday rules were temporarily suspended, they were not replaced by a state of chaotic anarchy. New rules came into effect. Fastnacht customs with a high representational value for a city’s society, such as the Nuremberg “Schembartlauf”, were perfectly organised productions in which every participant had a clearly defined role. Pictures of the main Schembart event (the storming of “Hell”, which was a ship on wheels in 1539) confirm this.

Storming of “Schembart Hell” in Nuremberg in 1539, depiction in a Schembart book from the collection of Sebastian Schedel, 16th century, Los Angeles, University of California, Library, Coll. 170. Ms. 351

The ‘Compagnie de la mère folle’ from Dijon

In some towns there were already special “foolish societies” before 1500, often with prominent members, which were responsible for organising Fastnacht and who also developed activities throughout the year. In Dijon, for example, this took the form of the “Society of the Mother Fool”, the “Compagnie de la mère folle”, or “Infanterie Dijonnaise” for short. It enjoyed widespread fame because, in addition to wealthy citizens, high clerics and important nobles were members of it – and sometimes even the “Office of the Mother Fool” itself was held by figures of royal status. So, for all of the institution’s humorous aspects, the rules within Fastnacht were at least as strict as those of everyday life. The society’s flag from the 16th century is still preserved: On the front it shows the “mère folle” in yellow and red with an open face mask and a crescent moon on her face. This is because Fastnacht is always around the new moon due to the date of Easter, which is based on the full moon of spring.

Front of the flag of the “Society of the Mother Fool” in Dijon (“Infanterie Dijonnaise”), 16th century, Dijon, Musée de la Vie bourguignonne

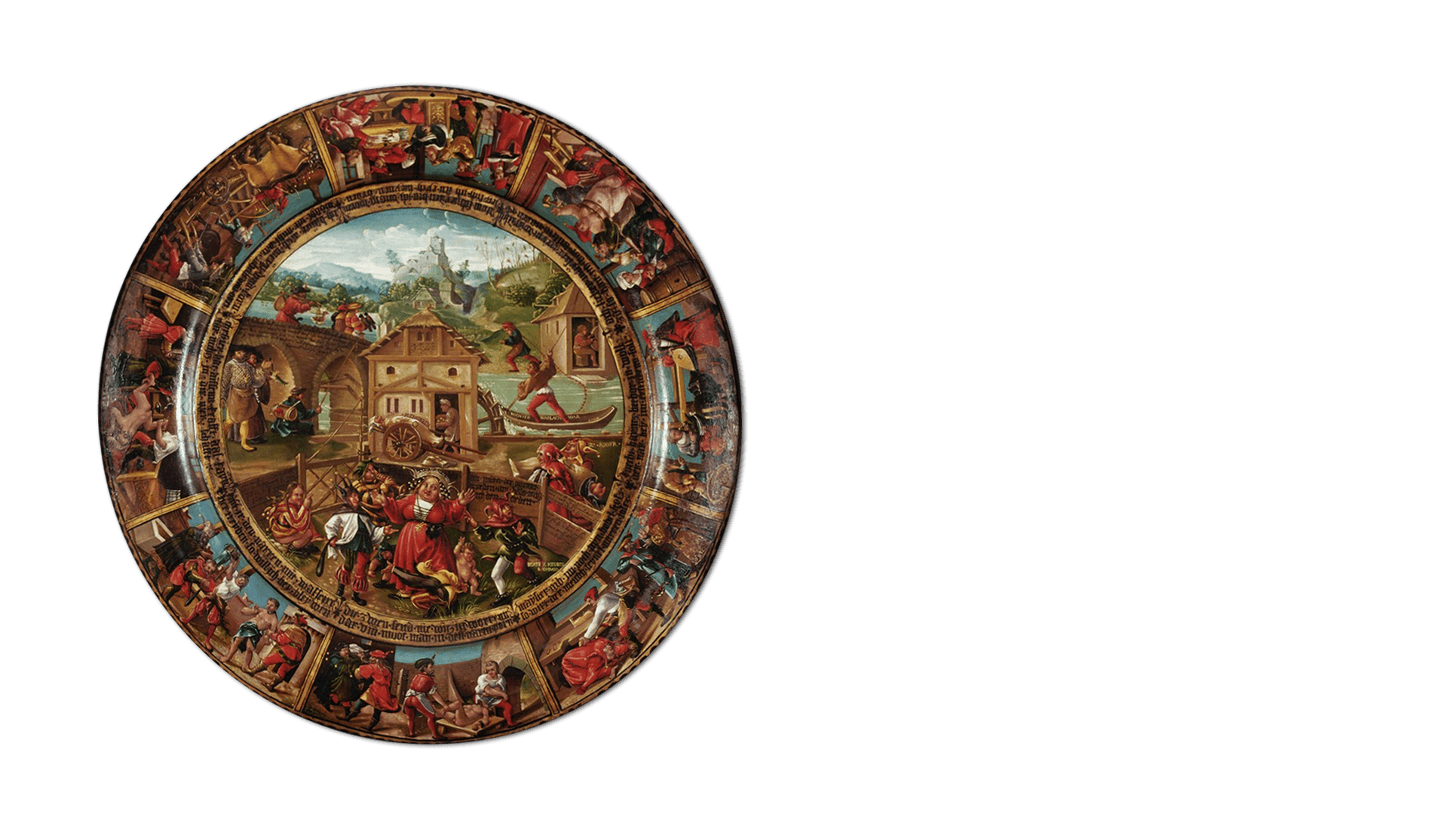

The Society of the Mother Fool from Augsburg

It has only recently become known that Augsburg also had a “Society of the Mother Fool” to organise Fastnacht, which seems to have been modelled on the legendary example set by Dijon. At their head was a “guild master of fools”. Among other things, this figure had to make sure that on official occasions all members wore their medal on their neck (a gold and silver forged fool’s head on a chain), in accordance with the statutes. In 1528, as a showpiece for its festivities, the society had a wooden ornamental plate almost 80 cm in diameter, ornately painted with scenes of foolishness and made in the workshop of the artist Jörg Breu the Younger. Its motifs revolved around the central figure of the mother fool, and can now be seen in Ambras Castle near Innsbruck. In the 1530s, the Augsburg society seems to have broken up due to internal urban conflicts, while the “Infanterie Dijonnaise” continued to exist until the middle of the 17th century.

Painted ornamental plate of a mother fool society in Augsburg from 1528, Augsburg, workshop of Jörg Breu the Younger, Schloss Ambras b. Innsbruck, Kunstkammer, Inv. No. P 4955

Early Fastnacht Leaders

Many council minutes show how meticulously urban Fastnacht festivities were organised. In Rottweil in 1614, for example, there was a bitter dispute between the young bakers and millers on the one hand and the blacksmiths’ servants on the other over the order in the Fastnacht procession. The council then established an alternating model, giving priority to one group in the first year and the other in the next. The Fastnacht procession order, then, was apparently just as prestigious and strictly regulated as the procession order on Corpus Christi. So there is no trace of anarchy and chaos. The exact opposite is the case. Another noteworthy reference is found in the council minutes dated 18 February 1655. There, some Fastnacht participants were punished for insubordinate behaviour during the festivities – including a certain “Johann Baptista Frantz, master of fools”, above all. So the position of a “chief Fastnacht official” apparently existed early on in Rottweil, too.

Strafen für unbotmäßige Fastnachtsnarren in Rottweil 1655, darunter Johann Baptista Frantz Narrenmeister, Ratsprotokoll Rottweil vom 18. Februar 1655, RPR p. 222

Sophisticated Rules of the Game

The fool’s court in Grosselfingen also testifies to the precise regulation of Fastnacht festivities. A handwritten book from the 18th century exists there, which is apparently a copy of a previously lost book from 1605. It lists all plot parts and roles, and contains numerous speech and song texts that are still obligatory today. This is another example of the meticulous order of Fastnacht, although the rules here are even more differentiated. Along with strict warnings not to change any core texts, the Grosselfingen prompt book also wisely allows limited space for improvisation. In this way, the participants with so-called “alleyway roles” and those directly involved in the “court proceedings” are each allowed to freely formulate their texts in order to be able to act with reference to current issues. Other roles do not allow this. The recipe for success therefore consists of a sophisticated mixture of repetitive and innovative elements, regimentation as well as spontaneity.

Title page of the book of the fool’s court of Grosselfingen, 1st half of the 18th century, copy of the lost statute book from 1605 with additions from 1719 and 1740, Grosselfingen, Archiv des amtierenden Narrenvogts

Reorganisation of Festivities from Above

After traditional Fastnacht festivities were increasingly rejected by the Enlightenment at the end of the 18th century as being no longer “contemporary”, and even came to a standstill in many places as a result of the Napoleonic upheavals, the future of Fastnacht did not look good. The urban educated bourgeoisie criticised the few remaining participants (mostly young men) for breaking with earlier rules, and sliding into the vulgar and offensive. In the face of this general decline, some prominent individuals in Cologne then developed a refined form of celebration along romantic lines, which came to life in 1823 in the first new-style procession. Significantly, the organisers called themselves the “Festordnendes Komitee” (“Festival Organising Committee”). At the base of the Rhenish Karneval, therefore, there was an explicitly regulatory body – and not some kind of chaos club. There was no trace of “resistance” or temporary revolution – Fastnacht was now all the more an expression of bourgeois order.

“Festordnendes Komitee” in Cologne 1823, coloured drawing, Cologne, Farina Archiv

Societies as Bearers of Fastnacht

As the 19th century progressed, the rapidly growing number of clubs and societies took control of Fastnacht. In southwestern Germany, where the Rhineland was a popular model from the 1840s at the latest, it was societies with names such as “Frohsinn”, “Amicitia”, “Heiterkeit” or “Narrhalla” that organised Fastnacht festivities and usually documented them in illustrated chronicles, which serve as important sources today. The Donaueschingen Fastnacht Society first appeared in 1853 under the name “Frohsinn” (“glee”), and immediately staged an original Fastnacht event that even included an excursion to the neighbouring town of Hüfingen. It kept its chronicle from 1856. On the title page, surrounded by tendrils and figurines, a “Hansel” from Donaueschingen is shown with his “Gretle” – a couple that had apparently already been known for a long time at that point, and that still makes an appearance today. It is worth noting that, despite Karneval influences from the Rhine, the traditional local masked figures were by no means completely displaced.

“Narrenchronik” from Donaueschingen, begun in 1853, title page, Bad Dürrheim, Archiv der Narrenzunft Frohsinn Bad Dürrheim

Fastnacht Guilds and Sense of Tradition

In Überlingen, the first society founded in 1863 was also called “Frohsinn”. The “Narrenbuch” (“fool’s book”) it created shows how important tradition was to those responsible from the last quarter of the 19th century, which ultimately also led to a turning away from Karneval-type forms in the southwest and a return to the old Fasnet figures of the region. The 1884 entry in the Überlingen Chronicle even explicitly states that the society wanted to help its successors “to do as their fathers did”. From the 1890s onwards, the societies increasingly began calling themselves “Fastnacht guilds” based on the “old German” model. After the First World War, the return to tradition finally reached its peak. For example, the text of the Rottweil fool’s march, written in 1919, reads: “And as long as imperial city blood / still flows through our veins, / we celebrate Fastnacht, / Fastnacht in its old splendour. / Hold high the old tradition, / never deviate from it.” Fastnacht, then, was now both a legacy and an obligation for its bearers.

“Narrenbuch” from Üblingen, begun in 1863, entry from 1884, Überlingen, Archiv der Narrenzunft, Überlingen, Stadtarchiv

Fastnacht Association with the Longest History

Up to and including the year 1924, Fastnacht remained banned in the states of Baden and Wuerttemberg due to the unstable political situation of the Weimar Republic. The entire tradition itself was close to collapse after a total of ten years of interruption. This prompted representatives from 13 Fastnacht guilds to meet in Villingen on 16 November 1924 and join together to form an interest group with the aim of defending Fastnacht as a cultural asset against political pressure, and to ensure that it could be practised again without obstruction from 1925 onwards. The initiative was successful. It laid the foundation for the oldest German Fastnacht association that still exists today. The minutes of the inaugural meeting are still preserved. With the creation of this institution, the degree of Fastnacht organisation – a historical turning point – entered a new stage on a supra-local level.

Minutes of the inaugural meeting of the “Gauverband badischer und württembergischer Narrenzünfte” (known since 1930 as the “Vereinigung schwäbisch-alemannischer Narrenzünfte”) in Villingen on 16 November 1924, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

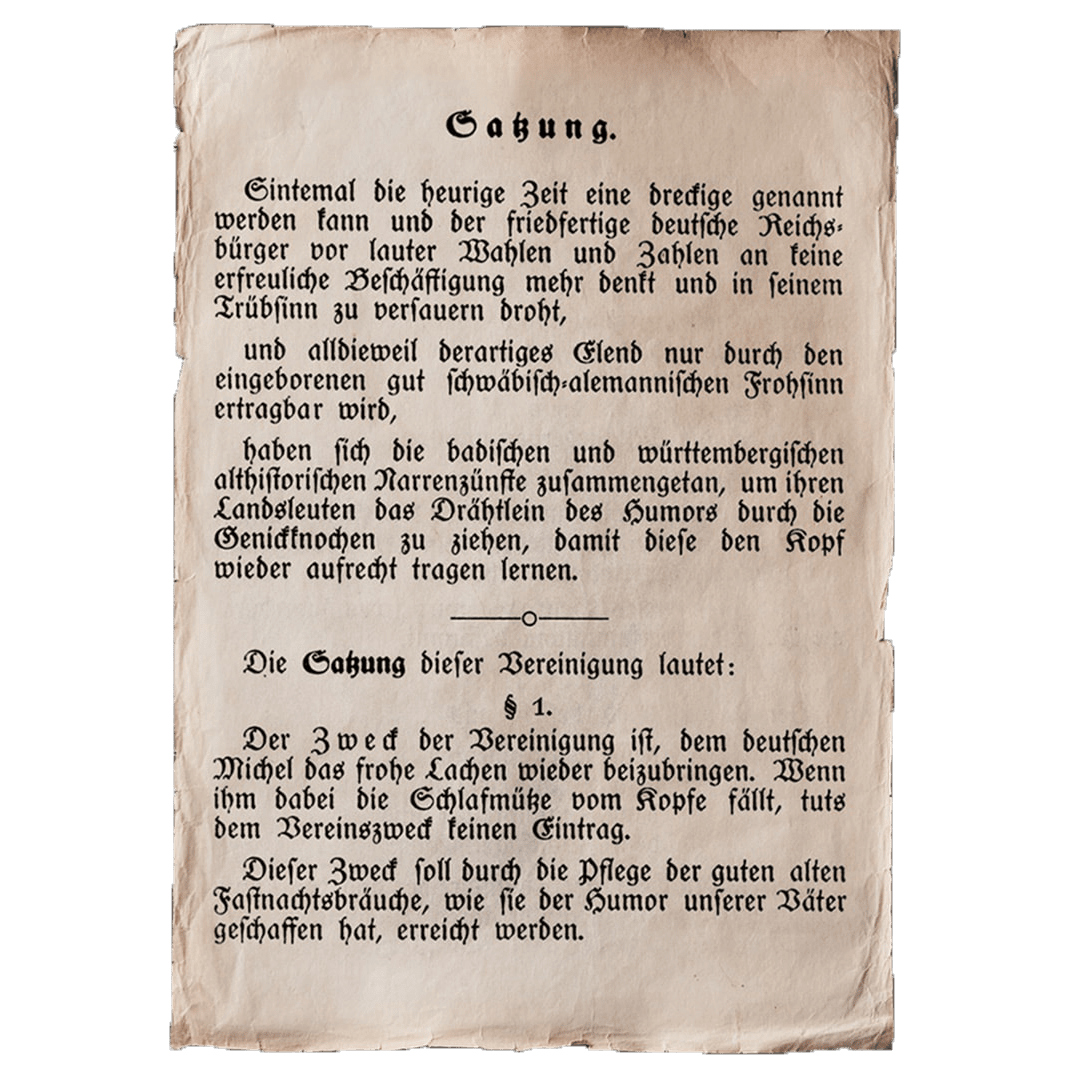

The Birth of ‘Swabian-Alemannic’

The first printed charter of the association – formulated in silly speak but soon replaced by a more serious style – contain a few remarkable details. It starts with the term “Swabian-Alemannic”, which had not previously been used in general terminology. In addition, when it speaks of “Baden and Wuerttemberg … Fastnacht guilds” having “joined forces”, this hints (though only in a Fastnacht context, of course) at the later combined German federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. And the use of the somewhat paradoxical phrase “old and historic” as a quality feature also points to an attempt to distance the founding guilds from less traditional ones. This shows a problematic internal distinction within the guilds themselves between “superior and inferior” customs, which would later lead to heated discussions.

First printed charter of the “Vereinigung badischer und württembergischer althistorischer Narrenzünfte” from 1924, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

Reason and Purpose of the Merger

Founded in 1924 as the “Gauverband badischer und württembergischer Narrenzünfte” and later renamed the “Vereinigung badisch-württembergischer althistorischer Narrenzünfte” (Association of Old and Historic Baden-Wuerttemberg Fastnacht Guilds), the association settled on its final name in 1930 by dropping the “old and historical” reference: “Vereinigung schwäbisch-alemannischer Narrenzünfte”, or “VSAN” for short. Even more important than its name, however, was the creation of a new form of event by the association in 1928 – the “Narrentreffen” (“fool’s meetings”), which are still held today on the weekends before Fastnacht in alternating location in southwestern Germany. They give spectators as well as participants the opportunity to gain an insight into the diversity of regional customs and masked figures. The first meeting of this kind in Freiburg also took place in a hall, but from 1929 onwards it was always accompanied by a large joint procession. The association’s main goal was to preserve traditional local customs, to promote their cultivation and to protect them from all kinds of external interference – not least from political influence from Nazi party organisations such as the “Kraft durch Freude” (“Strength through Joy”).

“Vereinigung badisch-württembergischer althistorischer Narrenzünfte”, poster for a “Narrentreffen” in Rottweil, designed by K.-F. Kaiser from Villingen, pre-Fastnacht period 1930 (detail), Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

Fastnacht and the Nazi ‘Gleichschaltung’

In 1937, the development in other regions towards supra-local forms of organising Fastnacht took on a new dimension. “All bodies, organisations, corporations and associations involved in German Karneval” were invited to Munich for 16 January of that year for the founding of a nation-wide “German Karneval Federation”. The initiative for this came directly from the Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda in Berlin, and it was very obviously in the spirit of the “Gleichschaltung” (forced coordination) of Nazi cultural policy. The totalitarian state wanted to use this to gain access to Fastnacht and Karneval festivities throughout the Nazi Reich. The fact that the VSAN only played a minor role in Munich at the time, and was not awarded a functionary post, later served to exonerate it. However, the new association was no longer able to make much of an ideological impact or exert any political influence anyway, because the Second World War brought all Fastnacht activities to a standstill from 1940 onwards.

Invitation to the inaugural meeting for the creation of a German Karneval Federation for 16 January 1937 in Munich, Bad Dürrheim, VSAN Archiv

The Association of Baden-Wuerttemberg Fastnacht Guilds today

After the occupying powers had initially dissolved all associations in 1945, the VSAN received its re-authorisation from the French military administration on 24 April 1949. In the 1950s, the association was marked by discussions about the understanding of tradition and questions of differentiation from the Rhenish Karneval, which even led to individual resignations. Nevertheless, the association grew steadily and today has 68 member guilds from eight regions, including northern Switzerland. The VSAN has formulated its goals in a mission statement. In addition to the oldest amalgamated group, there are now a good dozen other Fastnacht associations in southwestern Germany, with a total of over 600 member guilds. Taking into account independent guilds, there are around 1,000 local Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht groups today, which gives a rough idea of the expansive growth of this cultural form of expression in recent decades.

“Hansel” from Donaueschingen, photo: Marc Leon Schwarzer – logo of the “Vereinigung schwäbisch-alemannischer Narrenzünfte”

The German Karneval Federation today

The German Karneval Federation (“Bund Deutscher Karneval” or “BDK” for short) was founded in Mainz in 1953 and strongly dissociates itself from its Nazi predecessor (which is why the latter’s date of establishment is not counted in the former’s chronological timeline). Today it represents the the largest umbrella organisation of German Fastnacht and Karneval associations. It consists of 35 national associations and has more than 5,300 local member associations – which, according to its own estimates, means that it speaks for around 2.6 million active participants, including around 700,000 young people. Independent of the BDK, there are also other associations in the Rhineland as well as local clubs that are not affiliated with the amalgamated associations. All of this gives an idea of the breadth of the cultural phenomenon of Fastnacht, Fasching and Karneval. The main goals of the BDK are the promotion and support of Fastnacht customs, their representation in politics, youth work as well as academic research into the cultural heritage of Fastnacht (which is also the task of the VSAN). Similar to its mission statement, the BDK has laid down its philosophy in an ethics charter.

“Lappenclowns” in Cologne, photo: Festkomitee Kölner Karneval 1823 e. V. – logo of the Bund Deutscher Karneval

Regulated Enjoyment

To see Fastnacht as an “event of resistance”, a “temporary break with all forms of order” or even as a state of anarchy is to completely misjudge the festivities it entails. It is true that Fastnacht offers a chance to escape from everyday life, to slip into a different role, to act out emotions, to be silly, and to even go overboard a little. But all of this has to be done within clearly defined boundaries and not chaotically. It involves following rules and, in urban areas, a high degree of organisation early on. Very little in Fastnacht has developed “by itself”, “from below” or by chance. Most elements of the festivities (and especially the art of the masquerade) were inspired by elites, and are part of a complex history of development. This applies to both the fools as well as the devils from the processions. The ways Fastnacht is celebrated did not originate from how the lower social classes felt. They were the result of targeted design, and in this respect the educated bourgeoisie exerted a massive influence in from the 19th century onwards.

“Bändelenarro” from Zell am Harmersbach, photo: Marc Leon Schwarzer

Fastnacht als gesellschaftliche Aufgabe

Even in the late Middle Ages, the Fastnacht organisers were prosecuted if something went wrong. This is proved by countless entries in council minutes. But there is no comparison with the present: Today’s Fastnacht officials are burdened with a massive responsibility that is almost no longer reasonable. The regulations enforced by authorities for street processions alone are getting longer and longer. At the 2020 VSAN “Narrentreffen” in Bad Cannstatt, the safety plan alone comprised over 200 printed pages. Those who dedicate themselves to the festivities, who engage in voluntary work, who are personally liable and who sacrifice effort and time to give people a few hours of happiness are deserving of the highest amount of respect. Their Fastnacht efforts are aimed at a valuable idealistic heritage that is open to all, gives joy, creates identity and offers a sense of belonging. The “Jecken” of the Rhineland share this belief with the “Narren” of the southwest. It was with good reason, then, that both the Swabian-Alemannic Fastnacht and the Rhenish Karneval were entered into the National Register of Intangible Cultural Heritage by the German UNESCO Commission in 2014.

“Spielkartennarro” from Zell am Harmersbach, photo: Marc Leon Schwarzer